The Invisible

By Jason Metz

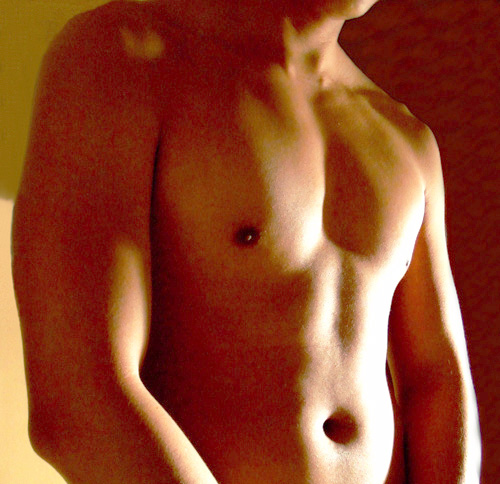

You do not see us, so let me show you. I’ll start here, with a needle. First, there’s an antiseptic pad to sterilize the injection area, to the left of the belly button, just below a birthmark. The needle is more like a fat pen, a pre-filled syringe encased in plastic with a trigger button at the top. Stand in front of the mirror, shirtless, the needle pressed up against the stomach, hold your breath. Click. It hurts. Not a lot, but enough to know that it’s there. It will pass. Ten seconds goes by, a slight gurgling sound as the plunger reaches the end of the barrel, then wait a few seconds more and remember to breathe. Wipe away the droplets of blood. This happens twice a month, on Tuesdays.

The commercial for my medicine has all of the typical scenes you’ve come to expect from the pharmaceutical industry: people trying to get on with their daily lives. They’re packing suitcases and boarding planes. They’re sitting in an Adirondack chair by a lake. They’re enjoying romantic dinners. These things happen while a hushed voiceover lists the potential side effects: serious and sometimes fatal infections and cancers, such as lymphoma have happened, as have blood, liver, and nervous system problems, serious allergic reactions, and new or worsening heart failure. All the good stuff.

None of it phases me. I know what life is like without the medicine. I enjoy packing suitcases and boarding planes and sitting by a lake. The romantic dinners are a little harder to come by, but not for lack of trying. The medicine allows me to try.

What does phase me, is when the commercial airs during football games. Friends, beers, wings. Trying to pretend that the advertisement for my medicine is just another commercial, couched between fast food ads and movie previews. The actors in the commercial represent my reality. This worries me. That the commercial might expose me, that my friends might catch on, that they’ll know something is wrong with me. If a deflection is necessary, I’ll make a joke and mock the commercial, get a laugh out of the room. Besides, these commercials are unnecessarily cruel reminders. They air at times when I’m trying to forget. When I’m living, trying to enjoy myself, keeping hidden. Sundays are for football. Every other Tuesday is for the needle.

I was born with an auto-immune disorder. There is no cure. For the rest of my life, some form of treatment is necessary. Without it, my quality of life plummets. And aside from all those physical symptoms and side effects, here’s what almost nobody tells you: The mental effects can cripple you. They will follow you at every step for the rest of your life. You will not be able to outrun them.

What might happen when you’re sick and always will be, is a depression that weaves its way in and out of your life. Sometimes it’s just a touch, barely there, you might not even notice it. Other times, it will consume you. It will corrode your needs and values and desires. There will be days that you cannot leave the house. You’ll find excuses to not be with friends. You will have great difficulty with intimacy. Those things that seem to come so easily for others. And you might find yourself staring out of a third story window, looking down at the ground, and thinking how easy it could be. Gone.

These might be passing thoughts, not even a suggestion, just more of an option to look at plainly. The fact that these thoughts exist within you is frightening enough, but there they are, so maybe it’s best to acknowledge them. Hang on the best you can and let them pass through. Remind yourself, these thoughts are foolish. It’s not all that bad.

There are other thoughts, too. For example, someone might come into your life. You might let your guard down, let someone get close. The problem with that is, eventually, you might have to talk about what you want for the future. This is where, if you don’t want to lie, if you’re strong enough to give the other person the honesty they deserve, you tell them that you do not want children. This will be a deal breaker for many. You can tell them the reasons why, that children just aren’t for you or that you don’t need to create a life to fulfill your own. There is some truth to this, maybe. But here you are, lying to someone you promised you would not lie to. Here you are, lying to yourself. Here is what you will never tell others. Here is the truth: that you’re afraid of what you’re going to pass down, what’s embedded in your DNA. How could you lovingly create a child and knowingly pass on your pain? How could you bear to watch that? How could you ask someone else to do the same?

It’s in these passing moments that you realize that every single day, even in the smallest of ways, you deal in terms of life and death, always. You are afraid to create one. You are afraid of your own. It’s in these passing moments that you are grateful for the medicine that alleviates your symptoms. It may not make these thoughts go away. But it gives you some distance. You can’t outrun these thoughts, but you can stay ahead.

* * *

You do not see us. But we are very much at risk. The Affordable Healthcare Act provides protection for those of us with pre-existing conditions, whether we were born with them or not. And here we are, once again, about to find ourselves at the mercy of the insurance industry. An industry that does not care for us. Without protections in place, they have the power to simply deny us coverage, or charge us exorbitant premiums that we cannot afford. Many of us will be forced to go without coverage, without treatment.

This is how they see us: We are ID numbers in a database. We are a math formula. We are X amount of dollars in premiums. We cost Y amount of dollars in treatments. We never come out in the black. The variable in this formula? Being born. Our complicity? To continually exist. In existence? More than 50 million of us.

We don’t want you to see us, but if you must, see us for what we are: human.

Don’t see us as simple mathematics, as a financial burden, or a losing proposition. We are not disposable.

We are the invisible. We swallow pills and stick ourselves with needles. We are among you. We watch football games and laugh at ourselves on TV. You invite us to your weddings and baby showers and hug us at funerals. We try to be role models to your children. We’re your best friends and, like you, we are trying to get through another day. We might not ask you for help because we too often see help as an admission of weakness. We are stubborn. We work so hard for our invisibility.

But know this: We are in grave danger. Know that we are here, alongside you. Know that we need you, now more than ever.

Jason Metz earned an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of California, Riverside. He lives in Somerville, Massachusetts, on the third floor of a triple-decker, on a hill that overlooks the Boston skyline, where he writes at a small wooden desk, resisting.

Photo credit: Takeshi Hiro via a Creative Commons license.

Thank you for sharing this exquisite, deeply personal piece. For what’s it’s worth, in concert with my Indivisible group, I’m on a mission to see that he does. Bravo to you!