Some Poems

By Nancy Dunlop

Brutal Things Must Be Said –James Baldwin

Some poems reside

in oven mitts, opening

the stove and reaching

for the pan with the leavened

bread flowing over its edges,

the mitts pull it out, piping

hot. A safe and soothing thing.

We are okay.

Some poems are like an arrow

in a bow, pulled taut, held

with great control, and then

released, the point

searing the air, straight

to the bull’s eye. Such poems

can be hard to watch without

flinching. You

avert your gaze before

the moment of puncture.

But what is the Poem to do? Not

hit its mark? Not speak?

Some poems wait

to be written on

the Reporter’s notepad, upon

arrival at the scene of

an accident. Yes,

it can be that acute

and chaotic and hard

to get the words to dribble

down the page, what with the

flashing lights, the mix

of bloodied coats, limbs

akimbo, sharp spikes of metal

and glinting glass. Just

getting through the barrier

of Yellow Tape surrounding

this type of poem can be

daunting.

But some poems

demand that much of you.

Some poems are loaded

guns, standing

in the corner of a Lady’s

bedroom. You will look

away from these poems,

unless they are tucked

in an anthology, padded by other,

softer Literature. The Professor

turns to this Emily

of a poem, asks

the class, What

does the gun represent? The students

come up with flailing

answers, or they don’t. Every

semester is different. The bell

rings, and it’s on to Psych 101.

Some poems contain

a knife blade, a bottle, a needle, a taser.

some poems rush their sick children

to the ER. Again. Some poems

are raped and constantly

interrupted. With flashback. Flashback. Flashback.

Such poems make it minute

to minute, if

they are lucky. They do not

have the luxury

to protest a Pipeline a trillion

miles away. Or, for others,

a Pipeline is the only thing they have

in front of them, getting

closer, bulldozers trenching

through their land. Tell me,

what is coming through

your front door?

Poems are like people. Each one

has a story, a dark thing they

carry.

You’ll see these poems lying in Hospice beds

when the Chemo stops working.

They use walkers, because their limbs

are dying. They are propped up in institutions,

alone and waiting for some nurse,

to bring a meal, so they can say hello

to someone today. Some poems

have distended bellies and parasites

crawling on them. Some crouch

on sidewalks, covered in cardboard.

Some poems are soldiers

home from combat, never finding

their words, never trusting anything, anybody

ever again. Some poems have survived

concentration camps and are branded

into the skin.

Some poems are typed

on Brown paper, Black paper,

fearing for their safety. Some

poems love other poems,

but are told they shouldn’t.

Such poems expect silence when they appear. Or

brutality. Never sure

of which. They have always

known that they will be

pushed to the margins,

until they fall off the edge

of the page on which they cling.

Some poems are called Nigger,

Cunt, Pocahantas, Fag, Irrelevant,

Wrong, No room

at the Inn.

But some poems can be found

in oven mitts, reaching

into a stove, pulling out

the finished loaf. Your family’s

favorite. You sit around the table,

and break bread, newly

nourished. You bless the world

inside and out your kitchen window,

a hum and patter of words draped

on the counter behind you,

in the oven mitts still warm, still

holding the memory of the shiver

and pop of the yeast, the stretch and

rip of the leavening

that makes way for the release,

the Rising. The final fruition.

Nancy Dunlop is a poet and essayist who resides in Upstate New York, where she has taught at the University at Albany. A finalist in the AWP Intro Journal Awards, she has been published in print journals including The Little Magazine, Writing on the Edge, 13th Moon: A Feminist Literary Magazine, Works and Days and Nadir, as well as in online publications such as Swank Writing, RI\FT, alterra, Miss Stein’s Drawing Room and Truck. She has forthcoming work in Free State Review and the anthology, Emergence, published by Kind of a Hurricane Press. Her work has also been heard on NPR.

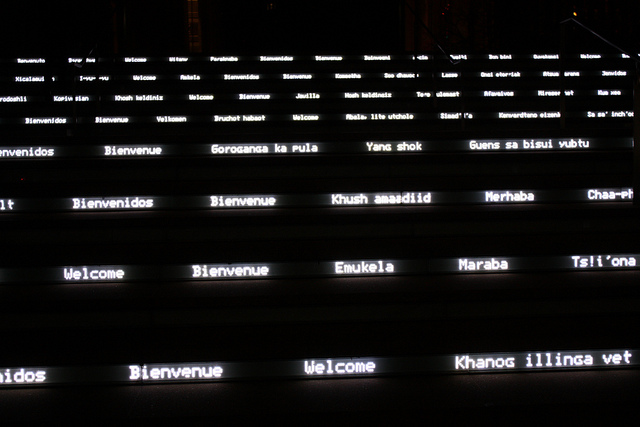

Photo credit: Guru Sno Studios via a Creative Commons license.