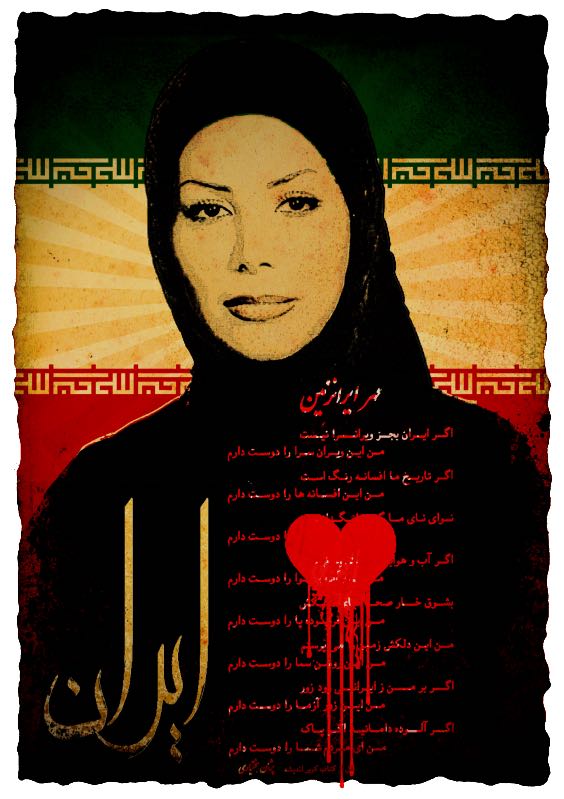

On a Side Street in Tehran a Woman Watches the Protest of Neda’s Death

By Penny Perry

“Make up should be for your

husband only,” my mother

says in my head. In real life,

she is home in her apartment,

blowing cool air on her second

cup of tea, filling out her grocery list.

“You don’t need a clock,

you can tell time by the tasks

she performs,” my father always half-

grumbles, half praises.

From the secret pocket of my hooded

black coat, I pluck

a small tube, too big for a bullet,

too small for a gun. I daub color

on dry lips.

Half a block away, a few women,

some young, some my age, shout slogans,

wave posters of Neda.

I promised my mother I wouldn’t

come anywhere near here. I tell myself

I will stay on this street. Spoiled olives

drop like bruises from the tree

on the sidewalk.

In this ten o’clock Saturday sun

the lipstick is the tentative pink

of a small smudge in a white

apple blossom.

Before Western books were banned

I bought Brontes and Austen from the book

store with the faded awning.

Those days, I walked to work

in heels, tilted my painted face

like a flower to the sun.

No policeman here to copy

my license plate, shatter

my windshield. I could climb

back in my car, drive by

the protestors, honk my horn,

wave two fingers in a victory V,

and speed home to my husband

and son. I pocket my lipstick, walk

toward the women,

one of them in a tight coat,

nervous streaks of eyeliner

like winding streets on her lids.

Two Basijis so young,

and not wearing their helmets,

stroll around the corner.

They are laughing, sipping sherbet.

Their truncheons loose in their hands.

They are like my cousin Isar

who believes women deserve

cut faces, split bones.

I should turn back. On this warm

day my head is hot under the hood

of my coat. I think of the night

my son was born, my prayer

of thanks that he was not a girl.

One of the men tosses the last

of his sherbet on a poster of Neda

abandoned on the sidewalk. I slide

behind a tree. I hope the Basijis

will rush past.

In my secret pocket, my phone rings.

Rubinstein’s sweet piano playing Chopin.

My mother’s Saturday call.

It is eleven o’clock.

Author’s note: When I was working on the poem I wasn’t thinking of myself as a white woman writing about an event from an Iranian woman’s first person point of view. I was caught up in Neda’s bravery and the bravery of the women protesting Neda’s death. Only now, looking back at the poem, I see there is a question in the poem that is personal to me. How brave would I, an American, middle-class white woman, be if protesting and marching meant not just the threat of arrest, but the possibility of dying and leaving a child motherless. That’s a question that I haven’t had to face and maybe that is one of the reasons I admire the Iranian women protestors so much.

Penny Perry is a six-time Pushcart Prize nominee in poetry and fiction. Her work has appeared in California Quarterly, Lilith, Redbook, Earth’s Daughter, the Paterson Literary Review and the San Diego Poetry Annual. Her first collection of poems, Santa Monica Disposal & Salvage (Garden Oak Press, 2012) earned praise from Marge Piercy, Steve Kowit, Diane Wakoski and Maria Mazziotti Gillan. She writes under two names, Penny Perry and Kate Harding.

Photo credit: Anonymous.