After the Splat

By Kate LaDew

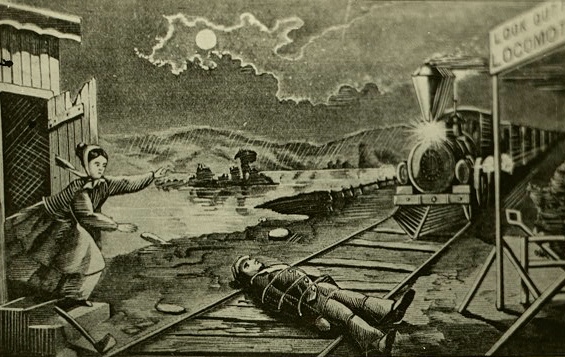

In 1867, the first instance of a hero saving their sweetheart from an oncoming train after a dastardly villain tied them to the tracks debuted in the last scene of a New York stage play.

The hero’s sweetheart calls for help, while the hero, locked inside the train station, watches from a barred window, searching for a way out. The villain disappears, off to be dastardly somewhere else, and the whistle of a locomotive sounds, the sweetheart’s cries grow frantic.

The door shudders from a blow on the other side. The hinges creak, the wood splinters and the door swings open, lock dangling, as the hero appears, out of breath, axe in hand.

The sweetheart calls again, beginning to sob, as the hero rushes forward, tearing at the ropes crisscrossed over the tracks, and pulls the sweetheart to safety a split second before the train barrels past.

The woman drops the axe, the man shrugs off the remnants of the rope and they embrace, each declaring undying love. The sweetheart marvels that his hero is capable of such bravery, yet not allowed the right to vote.

In 1867, the first instance of a hero saving their sweetheart from an oncoming train after a dastardly villain tied them to the tracks features the woman as hero, the man as sweetheart.

Every moment since that night, men have waited while women, with incredible patience, undo the cruel, illogical and sometimes just plain stupid acts of other men. The good, waiting men all the while wondering why the world is so unfair and “Oh! if only something could be done, by somebody, somewhere, about it all.” But it can’t be them, The Good Men, because someone has tied them to a train track, and don’t you hear the whistle? and won’t somebody think about them? down here all alone with all the other Good Men, waiting for somebody, somewhere to do something about it all? Never mind how they got here, and never mind that the ropes aren’t secure because the knots have been tied by The Bad Men, who only know how to tie women’s wrists.

Those Brave Strong Women who really deserve more, more pay and medical rights and safety and equal access and equality in general and all those things they blabber on about. Someday maybe, somebody, but right now, let’s deal with the train situation.

All The Good Men who have daughters and wives and sisters and mothers and really get it, truly, no really, feminism and such, and hey, where are you going? don’t you hear?—can’t you see?—I would do something, I swear, it’s just, these ropes, you know and I mean, I don’t agree with all the bad men, and I’m only laughing to fit in, and I don’t really believe—and if it were up to me—and I would never—and the light in that tunnel’s pretty bright, and the tracks are really rumbling, aren’t they? and is it just me or is it getting hotter, and that whistle’s pretty close, and I think that might be the tr—

After the splat, the woman sitting in the train station she built from scratch, feet on the desk she designed herself, pauses in the middle of a sentence in the paragraph of a chapter of a book she wrote. Looking up at the blue cloudless sky, past the glass skylight she can open whenever she wants, the woman asks all the other women in the room, feet up on their own desks, reading their own self-authored books, Hey, did you hear something?

Kate LaDew is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro with a BA in Studio Art. She resides in Graham, North Carolina, with her cats Charlie Chaplin and Janis Joplin.

Boris Badenov image: Fair use.

Train scene from Daly’s Under the Gaslight (1868).