Search Terms

By Holly Stovall

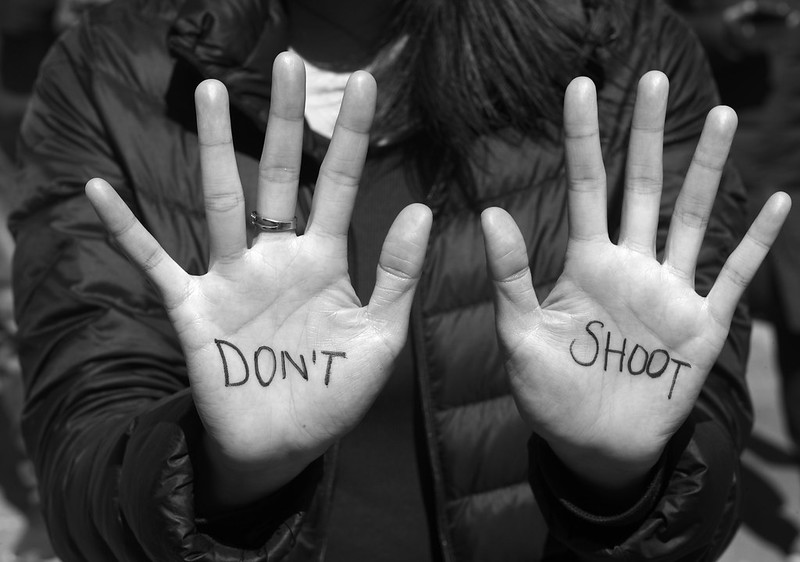

I opened the search bar, typed in “middle-aged women support Black Lives Matter” and narrowed the results to “images.” Google spit out a white couple, on the stairway in front of their mansion, pointing guns at protesters marching by. It’s not what I was looking for, but Google taunted me—Aren’t you curious? I clicked on the link.

What?! So now I’m standing under a pixelated oak tree holding a sign that says, “Abolish the Police,” while across the lawn, a man and a woman are aiming guns at me. The man with a gun is shorter than the woman with a gun, but his weapon is bigger. Their faces are pink, like pigs. Everything is lit—back lit, front lit, inner lit, and I’m in a multidimensional screen. I turn my sign over to show daisies on tall stems.

The woman is looking at me, but tilting her head towards him. “Who the fuck is this?” she says, and then, to me, “How did you get in here with us?”

Her pistol is polished. Her top is a navy French boating chemise with a sequin appliqué on the breast pocket. It overwhelms the pixel compactor and spews out blinding rays of fluorescence.

“Didn’t your daddy teach you not to point guns at people?” I say. “Aim it at the sky.”

I scan the perimeter of my vision for the “leave” option, but find none.

The woman explains that this isn’t Zoom; there’s no exit option. Her name is Kelly, and she doesn’t know how she and her husband, Brody, got swooshed in. They had been in opposite wings of the mansion. Kelly wants to know what I was doing when the search engine sucked me in, so I say I was just browsing the internet, clicking on random stuff.

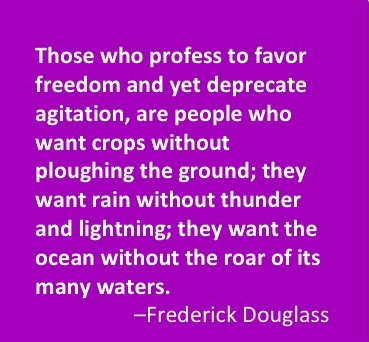

She lowers the gun and asks me about my search terms. Hers were “middle-aged women righteously threaten protesters with gun.” I don’t say what I’m thinking. First, that the adverb, righteously, is unnecessary. Also, that she’s the only middle-aged woman who rose to the top of Google results for waving guns at people practicing the right to free speech. Last, she embarrasses me.

I ask her if she has any theories about why Google generated me for her, but before she answers, Brody informs us that Google is an algorithm.

“Are you familiar with mansplaining?” I say, and then regret it because he’s wielding a fat automatic attached to a black strap slung across his hot pink Polo shirt. Even though we’re just pixels, the threat feels real, and I’m afraid. I don’t know the rules in here, but it seems I shouldn’t have pissed him off.

Kelly thanks Brody for his Google wisdom. “Hun,” she says, “go on up the steps. You should be above the rest of us.” He falls for that.

Kelly asks me if I was caught on video threatening nice suburbanites with BLM signs and causing Google to throw me out onto the first page of her search.

I explain to her that no, I live in a small town, west of the city, where we just stand on the edge of the park, next to the highway, and hold up protest signs for the delivery cars and hog carriers to see. There’re no mansion dwellers there who would aim guns at us.

I don’t tell her that I wrote an op-ed for the local paper, criticizing police for Kayla Montgomery’s death. Kayla was a blond woman who worked at the gas station and called me “dear,” even though I’m old enough to be her mom. A sheriff’s deputy pulled her over for what he claimed was “impudent driving” and shot her five times. She was unarmed. My column went viral on social media and generated pushback. That must be how I got on Google’s radar.

Brody descends to butt in again. “Did you hear me? Google results are generated by an algorithm. It’s just about how many hits a site gets. That’s all.”

His hot pink polo shirt contrasts nicely with the gunmetal of his weapon. His belt, though, is brown. Christ. He could have bothered to match his belt with his weapon. I tell him to Google “mansplain,” but I do it in a sweet voice, so I have an out if he gets angry.

“I’ll knock the lights out of you,” he says. He holds up his fists and lets the gun fall across his belly like a guitar. The pixels simulate smoke shooting out of his ears.

Kelly turns to him. “It’s a compliment, hon. Mansplain is what men do as an act of generosity towards women because our brains are small.” Brody turns and climbs back up the stairs.

Kelly wants to escape. She tells me that, before she got sucked in, she had a client who sent her an email saying she was trapped in a pixel compactor, and could Kelly please get her out and sue the search engine. The client claimed that when two people are Googling at the same time and their search terms intersect, the engine can get tangled, generate energy, and suck you in like a black hole.

I point out that she and I were each searching for middle-aged women who were involved in the protests.

“And we must have hit return at the exact same time,” Kelly says.

I ask her what made her enter “middle-aged women” in the search bar.

“I wanted to see women who look like me,” she says.

“Me too, women who look—” And before I finish my sentence, I’m swooshed back to the safe side of my laptop.

Later, Kelly phones me in this world, where things are soft, shadowed, cold and hot. I ask her what happened to Brody. He’s still in there, and she calls his current home the “mancompactor.” She claims he loves it because he can watch Fox News through the sight of his gun.

Holly A. Stovall has published short fiction, personal essays, literary histories, literary criticism, and scholarly research. Her creative writing appears in Writers Resist, Litbreak Magazine, and is forthcoming in Belle Point Press’s Mid/South Anthology. She holds a PhD in Spanish literature, an MA in Women’s History, and is currently an MFA candidate in Creative Writing at Northwestern University. She lives in rural Illinois with her spouse, teenage son, and standard poodle.

A note from Writers Resist:

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.