Five short stories by Amirah Al Wassif

Running away

My mouth is full of mice. I can’t talk or protest. I was born in the darkest spot of the world. My people hate the sun. They put the weight of the world on my tiny shoulders. When I was young, I was a great talker, but when I became 12 years old, they ordered me to shut my mouth up. My country is made of dust and sins. They don’t believe in girls’ voices. They say that when girls talk, the evil spirits spread.

I have to admit that I am not sure that my mouth is full of mice, but when my tribe circled around me like bees, they pointed to my mouth, shouting loudly: “Hide your ugly mice! Don’t speak! Don’t protest.”

Their anger showed me that I have to flush and run away for hiding. Instead of doing that. I made a hole in the wall and disappeared forever.

Hunger and satiety

At the same time when I was wondering, did my friend like my latest photo on the Instagram, a child died from hunger somewhere in the world.

We all bite our nails through watching the breaking news. We all recognize the fake ones. We all cry in front of war children posters. We all laugh at our mirrors.

My mother stands on a mountain of pillows for feeding my little brother. I am big enough to feed myself.

We have many delicious dishes. We are proud of our full plates. After finishing my own, I run in a hurry to bring another one, not because I feel hungry, but because we have a plenty of food. So it is a shame not to bring another one.

We never experienced hunger before. The first time we heard of it was when our neighbor’s daughter died. At her funeral, people said that she died because of hunger. Even when we all knew that, nobody cared.

Just a dream

Last night, I closed my eyes and I saw my mother and me sitting together in front of a brown oven, baking delicious bread in a clearing where some birds pecked our necks and backs.

My mother’s cheeks were colorful like a clown. I looked at her in a proud way. She was still beautiful, just like a young girl.

She had a dimple. A special one. One of those dimples that kiss the heart of the sun. You feel its warmth naturally, without trying so hard.

The dust that covered my mother’s eyelashes smelled of the ancient streets.

In the dream, there were grown mint leaves between my fingers. My mother grabbed one of them, trying her best to cut it off. I screamed. There was a lot of pain around my fingers.

We are farmers. We used to fill our pockets with laughs and stones, stumbling to the river to throw them. Our dearest friend, the river welcomes our greetings, competing with us to make the funniest jokes in the world. We are country people, so we and the river understand each other very well.

I have a music box within my chest. All my lifetime, I felt that I am the richest girl in the globe. We don’t have money, but we feel so wealthy. Our fortune is a mix of singing and giving. We sing for our folk. We used to give them. We used to plant for them, for us, for the whole world.

My mother kissed my right cheek in the dream. You are a winner, babe, she told me. You plant your land; don’t wait for the men to plant it for you.

I don’t have a father. My mother’s forever tale says that there is a toxic man, tricked her, married her and made her a pregnant child who suffered a lot because of this.

I don’t blame you for this, babe, my mother said to me. You are my blessed girl, I need you in my world, and we all here need your bravery.

The distant birds play hide and seek with my wishes. I pray for our land, I pray for getting stronger, I pray for the girls, for the poor mothers. I don’t pray for the abusive husbands.

Within my dream, the grace underneath my little feet, I am sinking in the arms of the universe, sipping the happiness water.

My mother’s milk isn’t enough now, I am trailing the buds with my fingers.

The sky breathes in and out through my hair.

I met you too, in my dream. You were smiling at me from your far land. I called you: “Lewis, don’t forget me, my love, don’t.”

You looked at me in your gentle way. Your eyes smelled of honey. I see a paradise lies inside them. “Don’t try to close them so much, my love.” I said to you, and you ran away behind the red sun’s reflection.

I understand how the sun was so jealous. I know that nature belongs to you.

I plant beans, tomatoes and flowers. You plant me like a poem inside your heart. How close we were in my dream! How far we are in the reality!

I still remember how many tears jammed in your eye, when I sighed and cried, telling you that I and my mother should leave this land. You still remember, don’t you? How I sobbed, how the sadness made a lake of salt in my heart.

That moment was the harshest moment in my lifetime, the words jumped in craziness from my mouth’s edge. You ate yourself in worry and pain.

In my dream, my mother advised me to stop crying. She told me that nobody deserves my tears. I pretended that I agreed with her, but in truth, I didn’t, because you deserve, my love, you aren’t them, you aren’t a toxic man like my father and like all those men who forced us to leave the land, who poisoned our plants, who stole our right to be women farmers.

In my dream, I shrugged. I felt like I lost my voice forever, but then, I woke up, half asleep, trying to hide my waterfall of tears.

I open my eyes wide: I am heading now to my mother’s graveyard, next to yours, where I am planning to plant a cactus, my love.

My dead husband’s secret

My dead husband plays hide and seek with me. I catch him every now and then playing guitar in front of our daughter’s framed photo. He also loves to act like a clown before our baby budgie birds. He believes they notice him.

I don’t say a word about that to my relatives. They won’t believe me. To be honest they will say that I am a crazy old woman who is looking desperately for a new man. I am not. I love my dead husband, and really, I see him wandering in our apartment all the time.

Every time I see him, I try my best to hurry, to follow him. I want to catch him. I am longing to kiss his cheeks. I dream of throwing myself into his arms.

But I can’t. As a disabled old woman who is sitting in her wheelchair, I can’t help it.

There is no one here to watch me. There is no one here to look after me. Only my dead husband shadow, dancing up there on the walls with the shadow of our dead daughter.

Injustice

I was born and raised in a box.

My body is a metaphor. I lost my voice when Adam planted a knife in my throat.

“Give up, Eve,” Adam said.

I pointed out to the Apple tree. I hopped from one corner to another inside the box. I was dying to shout. I wanted to announce my revolution. I was in trouble. A big one.

My voice is gone. I have no power, no words.

Adam was touching the apple curiously, tracing it with his fingers. The smile on his face. The sin on his hand.

He kept watching me from his place: I was moving in back and forth. He treated me like a monkey in a cage.

The last time I called Adam was a billion years ago, when he asked me what was the thing I see in my dreams that makes me feel good, although I’m imprisoned?

At that moment, I let him see the picture in my head. A magnificent photo of the apple tree, guiding me to the river of happiness.

When he saw the photo in my head, he sighed and smiled.

After a while, he sang and ran away to find the tree, and yes, Adam found it and owned it, before punishing me and cutting my tongue.

Amirah Al Wassif’s poems have appeared in several print and online publications including South Florida Poetry, Birmingham Arts Journal, Hawaii Review, The Meniscus, Chiron Review, The Hunger, Writers Resist, Right Now, and others. Amirah also has a poetry collection, For Those Who Don’t Know Chocolate (Poetic Justice Books & Arts, 2019), and a children’s book, The Cocoa Boy and Other Stories, published in February 2020.

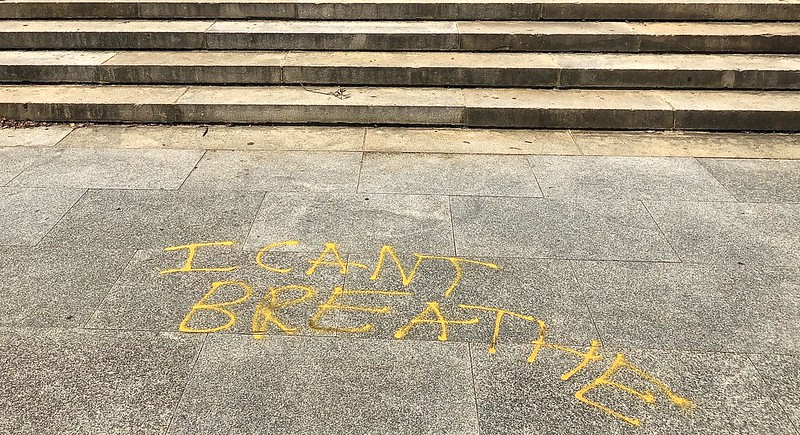

Photo credit: Andrew Malone via a Creative Commons license.

Writers Resist Readings at

Writers Resist Readings at

Now, looking forward, one of those things we have in the works is a couple of Writers Resist readings, hosted by the virtual

Now, looking forward, one of those things we have in the works is a couple of Writers Resist readings, hosted by the virtual