He Comes at Night

By J.M. Lasley

Editor’s warning: assault, self-harm, mental illness

He comes at night, when no one is watching.

The soles of his white shoes squeak on the shiny white floors, reflecting white lights above, humming and buzzing through night and day. The keys jingle-jangle and the door swings open, screaming.

He smells of sweat and the cigarettes he told his wife he quit smoking. Sometimes, like the first time, his breath stings my nose and my tongue: liquid fire from a flask he’s not supposed to sip from. He doesn’t care, he tells me, chattering as his fingers fumble with his belt. She’s a dumb bitch anyway and she’ll never know. Those idiots who run this place, they’ll never know, no one will know, and it will just keep happening.

The smoking, the drinking, and me.

I’m safe in the daytime, hidden amongst the bodies in the community room. I fold and fold bright squares of paper transformed into birds and butterflies, things I only see in pictures now that I’m here. I fold a lion to bite his legs and a tiger to roar him away, a bear to stand between us, with paws as big as my face.

They say we’re here because we’re mad. This is sometimes so. Sometimes I’m so mad I can feel it choking me, drowning me, my head lifting as I gasp for breath and the angry water spills up and out of me. That’s when they strap me, drag me kicking and screaming to the white room, to the bed, and I will have even less to fight him with between the straps and the pills. They taste like chalk and take the madness away. For a while. So I try not to get mad.

I try new things all the time. When it started, I tried kicking and screaming. But no one watches so no one came and the kicking and screaming only made his eyes sparkle and his breathing, fast.

No one asks about the bruises or the shadows. I can see them in the reflection of the window of my door. Not real glass. Real glass can shatter and cut and end, but this glass just bounces and breaks your knuckles when you hit it. I can only see myself dimly. But I can see the bruises and the shadows. Does he have magic? Is that how no one else can see? When the faces in the blue outfits do see them, eyes squinching behind their glasses, nose wrinkling, they mumble mutter, “She’s taken to hurting herself, poor thing.” More chalk and straps, more helpless nights.

No glass, no knives, no knitting, nothing poking, prodding, nails trimmed daily, nothing nowhere. Until the Big One broke the chair. Ferret, the tall skinny twitchy one, he had been swiping a pill or two from the Big One for days. Ferret is a Blue Shirt, not a White Shirt or a Body, but he takes the pills sometimes: the chalk we don’t want anyway, the chalk that sometimes the others need. He took too much for too many days and the Big One woke, a sleeping giant gone mad, real mad, breaking the chair over a White Shirt sending splinters skitter-scattering over the floor. Behind my chair, hands over my head, I felt one touch my foot. I lost my shoes again, which means a pinch from Nurse, but that’s how I felt it. Long, jagged, beautiful wood. Snatching it up, I tucked it under my bra band.

The giant has been taken down: a pebble to the brow or a needle to the arm, I wasn’t sure. They pat us down one by one, pulling bits of the chair or other contraband out of hair and pockets, waist bands. When they try to reach for my bra band I crouch and scream, as if I am scared, as if they are hurting me. They are not hurting me and I am not afraid, but they forget where they were searching. Others were not so clever, they did not hide their pieces before the White Shirts thought to check.

When I am put back in my room and the coast is clear I hide my treasure beneath my mattress, tucked in the coiling.

•

For a while I tried the not fighting. I lay and stared at the wall when he came, counting the squeaks of the bed frame, seeing faces in the cracks on the painted wall. The first time he cursed and left. Other times he tried to hurt me, tried to slap me back into madness, so that he could crush me into the pillow again. The faces on the wall smiled at me, and I smiled back.

Then a new body came to the playroom, the Community Room. Her face was young; behind her flat bangs she had wide eyes, round ears, a gap between her teeth. She was older than she looked, she would tell them when the old Nurses called her honey, baby, and the Whites called her sugar-pie. The soul in her eyes was older, that was plain as daylight through gridded windows. Her arms were decorated with the scars of her suffering, a tally for every sorrow. She folded birds with me, kindness in her gentle hands and the small smile she gave me when I clapped.

He would do her instead, he told me. He’d see if she’d give him what he was looking for. So, I fought again. Better me, who was filled with madness, than she who had only sorrow.

The girl is gone. She left yesterday, squeezing me tight and whispering sweet words of remembrance I know she has already forgotten outside these iron and stone walls. I hope she forgets me. I am glad she is gone. It is time to try again.

•

The door has been closed behind me, the lock clicking into place, the light inside taken away so that I am left under a thin blanket and darkness in my bed. When the calling and the footfalls stop, when the chatterings and cryings and crowings of the Bodies stop, I slip out of my bed and crawl under it. Between the coils, my wood waits. Grabbing it, I set to work.

For several nights I do this, between the time the light leaves and he comes. Sawing, sawing, pulling. I dispose of my work in pieces, so they will not know. I stuff the remnants in my bra, then into the trash when no one is looking. They think I’m mad, but I am more than mad.

The night comes. It is time to try. The light leaves, the lock clicks, the darkness settles. Before the sounds disappear, I lift up my mattress, slide onto the frame and then settle the mattress back down on top of me, hidden in the hole I have made. And I wait. My heart is loud in my ears, louder than I have ever heard it. Eventually it comes. The squeaking white shoes on the white floor. The jingle-jangle. The scream of the door. And then a new sound. He is surprised. I cannot put my hand over my mouth so I bite my lips between my teeth so that he cannot hear my glee. Now he thinks I am magic.

I hear his footsteps leave, squeaking down the hall and I hear his call to those who are not watching. He has triggered the alarm. I push the mattress up, slide out and then back on top of the mattress as it settles, covering myself with the blanket.

Many footsteps pad down the hallway, and people rush into the room. I blink open my eyes, pretending I was sleeping deeply, sitting up and rubbing my eyes. I look up at them—the White Shirts, the Blue Shirt and the Nurse.

They ask me questions, throwing words at me in anger. My eyes are wide at them, and I pull back, lifting my blanket up. Where did you go, they ask, how did you get out? I shake my head again and again. They begin to question him, begin to think maybe he is the mad one.

“Why was he in my room?”

It is the first time I have spoken to them in some time. Usually I sing—nonsense songs they call them but I know better. To me they are pink and yellow, blue and grey, and life lives within the sound in my ears. “Why did he come here?” I cock my head and wrinkle my nose. “Smells bad.”

I see their noses twitching, opening and closing as they take in the sour and the sting. Their eyes meet to trade secrets, and I sense when I become a Body again. Now he is the target. They pull him away, nothing wrong here, but they have some questions. I see the Blue Shirt pat his chest, feel the hidden flask in that chest pocket, see the sweat start to drip down his face. I giggle in glee when the door is closed because I am more than mad. I am clever like the fox that escaped the hound.

The next night, I hide again in my clever fox hole, and listen, telling my heart to not beat so loudly so I can hear if there are squeaking shoes. But nothing squeaks and the keys don’t jangle and the door doesn’t scream; I know that I am free. So, I come out, lie down on my lumpy bed and smile and smile as the stars dance me to sleep from beyond the bars.

Days pass and I don’t see him. I dance in the community room to the old music because I have slept, my bruises are fading, and there is less pain. But then, when I have not been mad enough for chalk for days and days so that I know the pills are not making me see the things that are not there that look there, he comes back. He does not look at me as he watches the bodies, but I know that in not looking he is staring directly at me. And I know that he will come again.

Each night I wait. I know he enjoys that I am waiting. In the morning he looks at me once, to see more and more shadows sleeping under my eyes and he smiles. And I wait. I know it is a matter of time before he comes. But I pretend to sleep every night. The squeaking goes up and down the hall and pauses—but there is no jingle-jangle. Not yet. He cannot come because they are watching.

Finally, I begin sleeping through the nights. Perhaps he will not come—perhaps they have learned their lesson and there are watchers now. The sparkle grows in his eyes as I tremble in my corner and I know that I am wrong. One day, as he passes me, his fingers prod me sharply in the back. I jump up and scream and soon there are White Shirts all around me and I know the chalk and straps are coming. I calm down but they make me take it anyway. I pretend to, but I hold the chalk behind my back tooth—they cannot see and they do not check too good. I know he will come tonight thinking they have taken the madness out of me and I will not be clever enough to hide.

He is only sort of right.

The white soled shoes squeak down the white floored hall, under humming white lights. Sweat drips down my back, my spine, like a slide. The keys jingle jangle. The door opens, screaming. He chatters at me while fumbling with his belt.

“Thought you had me good, didn’t you, little bitch. Well, if you thought I was rough before—”

I stop his chattering. I swing my arm down—the wood clenched in my fist, its ragged point like a spear—and then it is in his neck. When I pull it out, the wood is wet now, soaking it in, turning red instead of brown and his eyes are surprised, and this surprise is even better than before because I can see it. When he falls, his eyes still wide and his life pumping out of the hole I have made, I let him. White becomes pink and then red—the clothes, the floor, my hands.

I smile.

He came at night, when no one was watching.

J.M. Lasley believes that the greatest form of resistance is kindness and empathy. She lives in small town Georgia for now, where she keeps her dog company and lives a thousand lives through stories. Her short story “Wish Perfect” will be published in 2020.

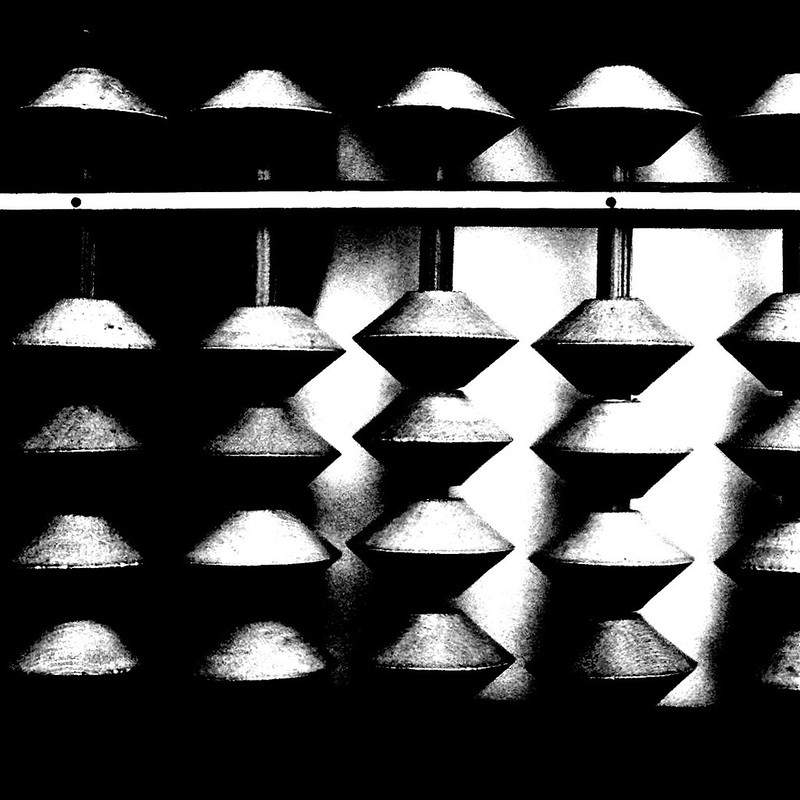

Photo by Andy Li on Unsplash.