A Reckoning

By Chinyere Onyekwere

“They’re here, Papa!” cried seven-year-old Kene Biko, careening into his father’s outstretched arms. They felt each other’s thundering heartbeats—had that kind of connection.

The sight of men cavorting on his property like they owned the place jolted Julius Biko, sent fear knifing through his innards. The dreaded land infringement conundrum was suddenly upon him.

The stricken look on Julius face struck a raw chord in his boy, evoked deep empathy and a sense of sickening trepidation. Soulful eyes teared as he watched his father caught up in a web of corrupt circumstances beyond his comprehension, their menace threatening the kind, mild-mannered man.

Frozen by the reality of the unfolding drama, father and son looked on helplessly with angst-filled eyes, as the men scurried around with their measuring tapes and an air of contemptuous resolve.

Five years earlier, Julius had taken advantage of Nigeria’s then roaring oil and gasoline economy to invest his hard-earned savings in erecting a petrol pump dispenser and miniature semi-detached brick house (serving as his office) in Omambala metropolis, near the green sprawling plains of Orange Grove neighborhood, a humble, thriving community named for the plentiful orange trees dotting its terrain.

His property stood tall and proud on the edge of an incline, enjoying modest patronage by motorists grateful to Julius for siting the petrol pump in the district’s outskirts where vehicles most likely needed to top up their petrol for their long-haul trips on the adjoining highway.

A meek, fastidious and law-abiding man, Julius had made painstaking efforts to keep in consonance with Omambala Town Planning’s property siting and landscaping guidelines, spelt out in a thirty-page handbook. He had jumped excruciating hurdles to acquire from the agency proper documentation and registration for the land— including the almighty Certificate of Occupancy, the most pertinent of the lot.

Julius’ woes came calling when a new breed of villainous scheming men insidiously infiltrated the OTP agency to corner the long-awaited roadway construction project by Nigeria state government. The expressway was mapped to run alongside Julius’ property.

Whisperings from the Orange Grove grapevine revealed the con men had arrogated to themselves absolute power. They were infamous for abhorrent practices of nullifying and erasing client’s land and registration records, railroading victims into a lifetime of litigation by a dubious state government—if the victims were too pig-headed to grease palms.

Graft rot ran deep in most establishments, including top echelons of power.

The men had surprised Julius with their unscheduled visit. They pontificated on the flagrant obtrusion by property owners on government projects, berated him for sabotaging efforts in getting the road constructed, and swiftly moved in unison, like a rampaging tsunami, to paste on the westside wall of his office, a red, six-foot-tall letter “X,” OTP’s ominous property demolition sign—and last straw that broke the camel’s back.

Julius squeezed his son in a tight embrace as if to shield the boy from life’s never-ending onslaughts.

Fate had again dealt the father and son duo a horrendous blow, quickening Julius’ descent into melancholic madness. He had struggled to make sense of his loss when the boy’s mother met her demise in a bungled cesarean delivery caused by a power outage that struck the maternity ward on the day his son came gasping into the world. Despite decades of independence, his nation had devolved into a baffling paradox—a land of great wealth plagued by privation.

Willfully repressed trauma simmered to the surface of Julius’ subconscious, had him grieving afresh for his beloved Ann, fueled him with defiance against a hellish system, galvanized him to pay OTP a visit—to set the records straight with the powers that be.

•

In the agency’s decrepit offices situated on the seedy side of town, Julius sat across from Jackson Dike, OTP’s Land Infringement Task Force head and, due to dire circumstances, the wrecking ball crane operator.

His amenable features did not fool Julius, who perceived the gluttonous pervert behind the man, who reminded him of a crocodile he’d once seen, its seemingly smiling demeanor strangely at odds with its deadliness.

“You had no right putting up that confounded sign on my wall,” said Julius, ditching pleasantries, looking directly into Jackson’s shifty eyes. “My property doesn’t encroach on the proposed roadway. My documents prove it, your records, too.”

“Says who?” snapped Jackson with snide arrogance, incensed that Julius had dared challenge his fiefdom. “My predecessors were reckless with records. Who knows?”

“Tell your meddling minions to keep away from my property,” Julius said with calm comportment that belied his fury. “I have no intention of playing in one of your convoluted games. I’d watch my steps if I were you, Mr. Dike.”

“Did you just threaten me right—”

“Did I?” cut in Julius. His sudden backward movement sent the cheap plastic armchair skittering on a worn and filthy vinyl floor.

“Get that despicable sign the hell off my wall,” glowered Julius before storming from the office.

“Expect my wrecking ball machine in the days ahead!” yelled the enforcer, caught off guard by the effrontery and scuttled pay-off.

•

That dusk, Kene watched his father’s every move. The man had left his food untouched, looked dangerously emaciated. Whatever was happening with his papa seemed fatally bad.

The boy put his arms around his father’s drooped shoulders in a show of loving comradeship.

“Stop worrying. We’ll be fine, Papa,” he comforted.

•

By the next morning, the curious Orange Grove neighborhood had caught wind of Julius’ run-in with OTP, and people looked on with bated breath as the wrecking ball machine rumbled up the incline, heaving its way toward Julius’ lot.

Jackson spewed a blizzard of profanities as his heavy vehicle grappled with treacherous terrain—and he choked with apoplectic rage at the sight of a young male child, his arms firmly clasped around the petrol pump.

Irked to be deterred by a mere street urchin, Jackson inched closer with his mammoth machine for the carefully planned assault. But the boy bravely stood his ground, did not budge an inch, ignoring his father’s frantic pleas to stand down, to clear out from the wrecking ball’s imminent path of destruction.

The stand-off morphed into an extended battle-of-wills. It attracted mainstream media that honed in for the kill like a cackle of ravenous hyenas, capturing the father and son’s pitiable plight.

But Jackson’s depraved sadism came to an inglorious halt when, in a bizarre twist of events, the machine’s massive tyres lurched, skidded out of control, and sent the steel ball on an erratic pendulum swing. It smashed the crane’s cab windows to smithereens with an earth shattering blow that reverberated around the neighborhood.

Jackson hardly knew what hit him when flying glass shards blinded him. He was bundled off the lot screaming like a demented soul from the pit of hell.

As if the tempestuous spectacle playing out on Julius’ lot was not enough uproar for one day, a disgruntled arsonist with a score to settle had a momentous meltdown and purged OTP of its long overdue excesses.

The headline, “A DAY FOR THE UNDERDOG,” and a large image of the colossal wrecking ball pitted against the puny child protesting the demolition of his father’s property, were emblazoned across the front cover of Nigeria’s leading newspaper and foreign bureau tabloids. It became an iconic symbol of a system’s tyranny over its long-suffering citizens, sparking outrage, a beastly backlash against government, and a clamour for justice for the hapless little boy, who received an outpouring of love never before witnessed within or beyond national borders.

•

“They’re here, Papa!” shrieked Kene gleefully, as road dust heralded a gleaming white SUV racing up the incline.

A Nigerian couple spearheading a nonprofit organization helping motherless children had followed Kene’s poignant story with keen interest—had lovingly opted to cater for his welfare until teenhood.

“I’m off to boarding school. You’ll visit me soon won’t you, Papa?” Kene’s eyes sparkled with unfettered excitement.

“Of course son, you bet I will,” Julius said, tearing up.

They hugged each other tightly and shared the joyful pounding of their hearts.

Chinyere Onyekwere is a freelance graphic designer and self-published author in Nigeria. Her passion for the written word won her Nigeria’s 2006/2007 National Essay Competition Award with her story titled “Motion Picture and The Nigerian Image.” Chinyere holds a master’s degree in Business Administration from the University of Nigeria. When she’s not glued to the computer screen, Chinyere keenly observes human conditions and the state of the world in general, while trying very hard not to be hoodwinked by her mischievous grand twins. She’s currently working on several short stories. You can reach her at ockbronchi@gmail.com.

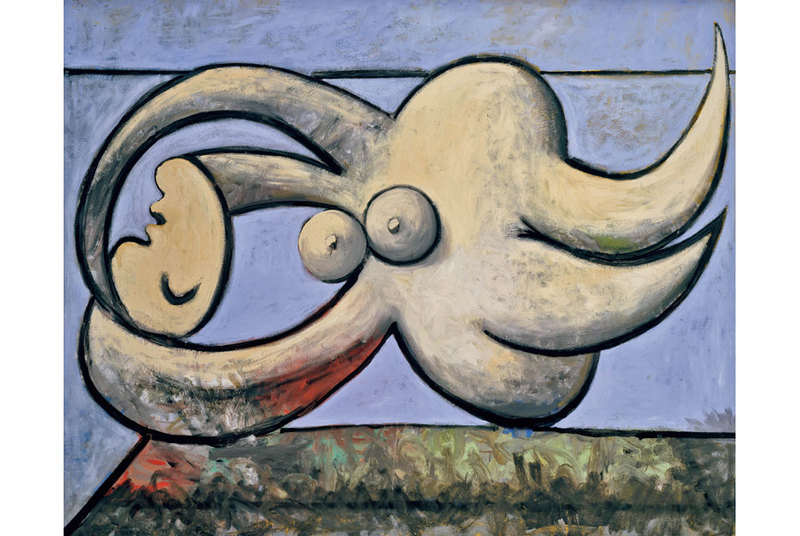

Photo credit: imageartifacts via a Creative Commons license.

We are delighted to introduce our new editor, Ying Wu, who is joining editor Laura Orem in the Writers Resist world of poetry.

We are delighted to introduce our new editor, Ying Wu, who is joining editor Laura Orem in the Writers Resist world of poetry.