Tayaran

By Christa Miller

The first time Haitham flies he is trying to flee the gang of teenagers in the camp who think he has something worth stealing. He is running, running, and then there is a building before him, the kitchen where his mother works during the day. Before he knows what he is doing, he takes two steps up the concrete-block wall, grasps the edge of the roof, and hauls himself upwards. He scrambles to the top and there he stays while the boys bellow and whoop below. Eventually they get bored and go off, and that is when he takes flight. A few running steps along the shallow pitch and then launch, he soars into the air. But young boys do not have wings. As he falls he has just enough time to tuck himself into a ball so he can roll along the ground.

His shoulder is sore for four days afterward. But he has tasted the air, felt it cushioning his body. It is gritty with sand and tastes bitter like turmeric, he wants to taste and feel it again.

Haitham has wanted to fly ever since he and his mother first came to the camp. They crossed the border late at night on foot, knotted tightly together with other families for protection from the government forces. Then just five, he wanted to be a bird so he could swoop into the air to escape without his feet and legs aching, without his knees and shins bloodied and bruised from his numerous stumbles and falls in the rocky sand.

He is nine now. The next time he flies, it is not to escape, but to see what else he can do, how far he can go in this tent city of a refugee camp. He has seen other boys fly on YouTube, where he watches videos of something called “parkour.” While his friends play video games that allow them to capture the government flag with guns and bombs and flame, he sits in the corner of his tent with his phone, watching boys in faraway cities—Berlin, Paris, Toronto, even Essen where his uncle now lives—balance atop high rooftops and leap from one roof to the next.

He cannot jump from tent to tent, of course, but the caravans in camp have hard rooftop surfaces. He pretends he is back in his old apartment building in Homs. His movements are awkward, tentative, a boy simply jumping from caravan to caravan, not the light tiptoe touch-and-go of the run across them he has envisioned. He tells himself this is merely because he does not yet know the camp’s layout, that, like the birds, he will come to know where it is safe to land.

But after he lands hard on the fifth caravan, a woman comes out, her jilbab flapping in a way that makes Haitham think she has pulled it on hastily. He climbs down rather than leap and roll, and he makes his apologies to her, shame warming his cheeks because he has made her risk her covering in public.

She rails at him for disturbing other people’s homes, their quiet spaces, their private time. And then, unexpectedly, her face softens. She is not angry after all, just startled, and he realizes that he reminds her of someone as she holds out her arms to him. He accepts her hug. She is a young woman whose dark eyes are warm and sad, and she holds on to him for longer than he expects. When at last she lets him go, tears have tracked down the high bones of her cheeks. Before Haitham can speak, she spins and disappears inside her caravan.

After this he—they—makes a game of it. Around the same time every day, he lands hard on her roof; she comes out and scolds him, then offers him tea and some basic riz. From her stove it tastes better than anyone else’s riz, including his mother’s. They sit in the baked shade of her caravan, and they talk. She is from Damascus, and she has never heard of parkour. Before the war she was a university student, she tells him, studying architecture, but after the men in her family were gone, she had to take a job cleaning the classrooms she once learned in. When he asks her who she came here with, her eyes grow faraway and sad, and she does not answer.

Still it is better conversation than Haitham can find with his own mother, who doesn’t seem to notice when Haitham slips away, who bursts into tears without warning, who mutters to herself about the things she left behind. It’s as if she has abandoned the family members who gave them to her, although the rest of them escaped to Germany long ago. If she only knew where her husband was, Haitham hears her tell the other women in the kitchen, she would rejoin him. She would rather be killed there than be trapped here.

Haitham flies to escape her tears, to escape the tiny space that is perhaps the size of one room of their old home, to escape the neighbors on either side who tell them they may have to live here for years yet, years before they can flee to Germany or Canada to start again. He flies to escape the knowledge that his mother’s dreams seem to hold no place for him.

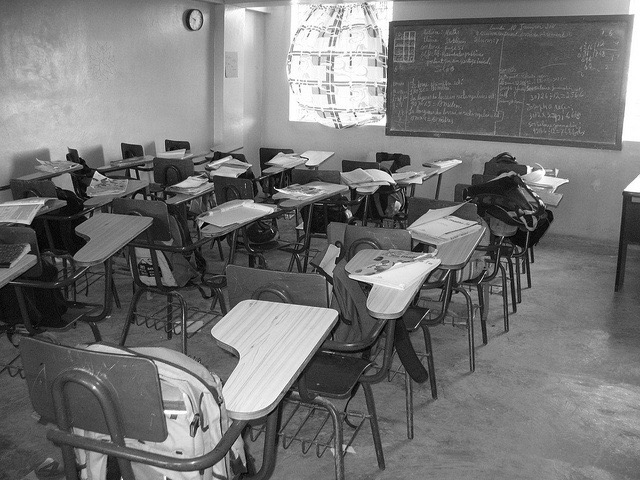

His new friend, Amal, tells him she thinks he should attend school in the camp. Why spend his days running around, she asks, her face creased with worry, where the older boys can torment him? School is safe. In school he will give himself a better chance to make it wherever he ends up. How can he tell her that school is the last place that feels safe? Bad enough that the mortar fire, far away as it is, makes her entire caravan shake; how can he explain to her what it felt like, to have seen his old school building in crumpled ruins, to realize that, had the shelling happened just a few hours later, he would never have known what hit him?

He flies to escape the mortar shells.

Before long he realizes that he has achieved the ability to touch and go, to kiss the corrugated metal rooftops with just the tips of his toes before sprinting to the next. He balances carefully on beams in construction sites. He teaches himself to launch his body and climb up the cinder-block walls of shelters and kitchens like a spider; to tuck-and-roll, as he did that first day, when there is nothing but empty space to fly through. He can go anywhere, be anything. He hardly notices when the people on the ground point him out.

That is why it surprises him one evening, not far from the market, to come out of a roll only to hurtle into another human body. For a moment he thinks it is Amal, this is near where she lives, but there is too little fabric for a jilbab. He steps backward, gazes into the hard face of one of the teenagers he has been flying to avoid.

He doesn’t know if these are the same boys who have tried to rob him. He has nothing, he tells them, but they don’t care about that. They have seen him fly, and they want him to use his skills. For Allah, they tell him, al-Nusra has a plan for you. You could return to Homs, live as a man. Surely you can make use of your speed for His glory?

Haitham does not know how they know he is from Homs. Perhaps once they were neighbors. It doesn’t matter. If he were ever to return to Homs it would be to fight at his father’s side, not for al-Nusra. He feels afraid, deeply afraid in the very center of his core, for he knows these boys do not want him to rejoin his father, nor do they believe in Allah’s grace or mercy. He knows it is not money the boys want to rob him of, but his very life. He does not know how he manages to slip between the knot they have formed around him, but he does, and he hears them laugh like the striped hyenas who skulk around the edges of the camp in the night.

The next day he remains with his mother in their caravan. When his friend Sabir comes to the door and asks if he can play, he declines. But his mother invites Sabir inside, and for the remainder of the afternoon the two boys huddle on Haitham’s bedroll, playing video games on their phones.

Haitham avoids YouTube altogether.

After three days Haitham begins to feel the familiar twitch in his legs telling him it has been too long since he has flown, he must practice. Still he does not go outside. His mother, teary-eyed, asks him what is wrong, but he cannot tell her, he cannot give her one more thing to cry about. He says simply that he injured himself and needs rest. Sabir continues to come over. Their other friend Khalil stops by after school. Khalil talks about what he is learning, asks Haitham and Sabir to join him. Haitham asks if he can still feel the mortar shells shake that building. Khalil doesn’t answer.

On the sixth day, Haitham can no longer bear the hot stuffiness of his mother’s caravan, so on the morning of the seventh day, after his mother has gone to the kitchen, he crawls out of the caravan’s window and up onto the roof. He lies flat on his back so no one else can see him, and he breathes deeply as the camp begins to rise around him.

Before long he hears voices at the nearby kitchen. A woman is looking for someone, a lost child. Her voice is near tears but still she sounds familiar, a voice Haitham remembers, from Homs perhaps? He turns over onto his belly and spies.

He recognizes Amal’s black jilbab right away, because it stands out so in a land of white tents and the brightly colored jilbabs that his mother and other women wear as if to brighten drab days, or to stave off darkness. Amal is teary, and she is speaking with his own mother, and it takes him several moments to realize that it is he she asks about, not some younger brother or neighbor’s son she was responsible for. He scrambles down from his mother’s caravan and goes to the two women, his face cast down at the dusty ground, ashamed again for causing Amal such grief, and for embarrassing his mother, though he is not sure how.

Amal catches him up in a hug, holding him as if she will never let go. When she finally does free him, he expects a scolding, but instead she looks deep into his eyes as if searching his soul, and he cannot look away. Finally, she asks, if she can find a way to teach him how to buy and sell in the market, will he come with her?

Haitham glances up at his mother, whose eyes and mouth have formed round Os of surprise. He sees something else dawning in them as well: hope, the same hope he sees in Amal’s face and hears in her name. He cannot bear to disappoint either his mother or his friend, and so he says yes.

The next morning he wakes up with his mother, who fusses over him in a way he cannot recall her doing since before they left Homs. She makes him a good breakfast of pita and vegetables, and she tells him that if there is ever a hope of his leaving this camp, learning how to run a business is it.

Amal has found him a job cleaning a flower shop. He is to sweep the outside and the inside of cuttings and fallen petals and deadheads. In exchange, the shop owner, a man named Mohsin, will teach him how to set prices and haggle and make change.

In the beginning, the responsibility excites Haitham. He sweeps meticulously, inside and out, making sure the corners are free of dust and cuttings and insects, and he listens to Mohsin haggle with customers. Several times Mohsin calls him over to watch how he makes change. He is given a piece of fruit for lunch, and he eats it behind the shop so that he will not disturb the customers.

But after a few days the excitement wears off. Mohsin seems to forget that Haitham is there. He doesn’t praise his new young worker for a job well done, nor does he scold him when he finds Haitham underfoot. He even begins to forget to involve Haitham in the purchase and sale process. It is not, Haitham reflects, as if he is the man’s son or nephew, or the son or nephew of Amal, who herself seems to have disappeared. Mohsin doesn’t seem to care whether he shows up or not.

One morning, Haitham leaves the caravan as if he is going to work, but instead he spends the day flying.

It feels good to be on the rooftops and in the air once again. It has been too long. He is stiff, his movements less fluid, and neither the air nor the ground are very forgiving. By lunchtime, he is winded and a little bit sore, but he keeps going.

While he flies, he thinks. About his mother telling him that the only way out of the camp is to learn a trade. About the things she says to the other women at the kitchen, how her husband needs her more than her son does. About the al-Nusra fighters who want him to return to Homs.

If he joins them, he wonders, if he pretends to fight for them, could he eventually find his way back to his father?

He is so lost in his thoughts that he does not even notice Amal until she plucks him out of the air.

Actually, she swats his foot as he flies above her head. It isn’t enough for him to fall, but it’s enough to make him stop running, to halt on the roof he lands on, to make his way down to the ground carefully rather than in the tuck-and-roll he hasn’t done since the day the older boys encircled him.

She isn’t alone. She is with his mother. He braces himself for the scolding, though he feels no shame this time and does not hang his head. He stares defiantly at the two women.

His mother holds aloft a paper with writing on it. She is triumphant as she tells him that she has heard from her brother in Germany. He is traveling here to Jordan to take Haitham away, bring him to Essen. He will attend school with his cousins and perhaps work in his uncle’s shop.

When his mother is finished speaking she gestures to Amal, who regards Haitham with great sad eyes. Amal kneels, takes both his hands in hers. “Haitham,” she says softly. “Your name means ‘young eagle.’ I should have remembered, eagles cannot be caged—in shops or in schools.” Her dark eyes twinkle when she says this. Then they grow somber once more. “Nor in camps. Isn’t that so?”

Haitham doesn’t blink. He pulls his hands from hers. Over her shoulder the hyena-boys skulk. He tells her, tells his mother, that he wants to soar far away. To find his father, to fight for Syria, to recapture his home for his mother, for Amal, for everyone in the camp who cannot fly. His words hang in the air between them.

Finally his mother speaks. “No,” she tells him. “There is no life for you there. Only death.”

“But you speak about rejoining Abee,” he cries.

At this, his mother drops her gaze to the dust at her feet. “Yes, and I am wrong. I miss your father, but not enough to risk your life.”

“Al-Nusra is as much a cage as this camp,” Amal tells him.

“Cages are everywhere,” he spits back.

Even as he says it, though, he recalls the parkour videos filmed in Essen, in the other cities. Those boys must attend school and work in shops, too. What if he could become the one to post videos on YouTube, give hope to some other boy who yearns to escape the camp?

He meets Amal’s gaze, then his mother’s. He smiles. In Essen, the air will be lighter to fly through, not full of heat and sand, and it will taste as sweet as honey.

Too goody-two-shoes for the rebels and too rebellious for the good girls and boys, Christa Miller writes fiction, which, like herself, doesn’t quite fit in. A professional writer for more than fifteen years, Christa has written in a variety of genres ranging from crime fiction to horror to children’s, but her favorite stories to write—and read—are those that blend genres. Her work has been published in both Volumes 1 and 2 of the Running Wild Novella Anthology, a 2008 anthology called Northern Haunts, in Shroud Magazine, Out of the Gutter Magazine, Spinetingler Magazine, and in a handful of online zines. Her affinity for the dark, psychological, and somewhat bizarre doesn’t stop her from snuggling baby animals as a volunteer at a local wildlife rescue, adventuring with her two sons in rivers, swamps and salt marshes, or relaxing with a good book and a cold beverage in her hammock. Christa is based in Greenville, SC. You can find her at www.ChristaMMiller.com and on Goodreads, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

Photo credit: Marco Gomez via a Creative Commons license.