Two poems by Ginny Lowe Connors

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” hundred_percent_height=”no” hundred_percent_height_scroll=”no” hundred_percent_height_center_content=”yes” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” enable_mobile=”no” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=””][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_2″ layout=”1_2″ spacing=”” center_content=”no” link=”” target=”_self” min_height=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”left top” background_repeat=”no-repeat” hover_type=”none” border_size=”0″ border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” padding=”” dimension_margin=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=”” last=”no”][fusion_text]

Onslaught

It spins like a gyroscope,

Our planet. My head.

Wobbles like a promise

too difficult to keep

as the news comes crashing

this way—space stones

hurling toward us from beyond

or from that hidden place

we carry within—

a secret darkness,

unknowable, unthinkable.

O disaster with a tail of flame

you’re hurtling this way again

you’re cratering my brain

and all the pretty cities we have built.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][fusion_builder_column type=”1_2″ layout=”1_2″ spacing=”” center_content=”no” link=”” target=”_self” min_height=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”left top” background_repeat=”no-repeat” hover_type=”none” border_size=”0″ border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” padding=”” dimension_margin=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=”” last=”no”][fusion_text]

Forget about It

Hit the snooze button, my fellow Americans,

hit the slot machines. Turn the page, switch

the channel, toss another steak on the barbeque.

Pay no attention to the plagues, the projectiles,

the flying limbs, or to the children who look

toward us, as if we could explain. Tell them our

electrons are all abuzz, they’re attracted, they’re

repelled by the golden glow beyond the power

plants, dust floating everywhere, fires we can’t

explain, flames that have replaced the eyes

of the last coyotes. No wonder we’re running

in circles, no wonder we’re all falling down.

Tell them the towers emit messages of evil

straight into our brains, bzzzt, zap, it makes

us a little crazy, ha ha, our heads floating off

like balloons. Our cell phones spy on us

as we sleep. We’ll turn away, we’ll wander

through the mall, what could be more

American, Big Mac ourselves to smithereens,

to oblivion. Our duty: to be oblivious, to be one

nation, under god, our father up in heaven—but he’s not

coming back, our family’s splintered, rearranged,

commandeered, forever changed, and we’re blind,

and we’re deaf but still yakking, yakking

all the time on the streets, in the vehicles we use

to slaughter our own beautiful hopped-up, zoned-out

young and we keep yakking in the ten million

aisles of merchandise because our family values

the plastic water, artificial turf, Barbie’s sharp

stiletto heels, size of fingernails, size of the astrodome,

home, sweet home, and no, you don’t need,

you’re American, you don’t need to explain

reality, it’s something we watch on TV. If

the desert’s erupting with blood, we’ll pump it with a derrick,

we’ll swill it like cheap wine. We’re chugging

Mai Lai cocktails, chowing down on hot wings straight

from Hiroshima, hot as hell, we’re spitting out the bones,

and if your appetite’s the kind that gnaws at you, gnaws

at you, gnaws, there’s Charlottesville stew a-simmering,

we’ve saved some just for you— we’re stuffing

ourselves silly, we’re tweeting, we’re plugging into iTunes,

it’s all the rage. All the rage. Children strut the streets

in tee-shirts sporting photos of their dead, shot,

stabbed, another one today, did you know him?

I heard his sister moan No, not him, while his best

boy insisted he was turnin’ his life around. His blood,

it soaked the ground as this old wound, our so-called

world, kept turning itself, turning itself around.

Don’t wait for the facts, let it all just spin itself out.

Let the ground turn itself over, let the trees splinter.

Let the hurricanes howl, let glaciers creep over us again

with their slow, cold, pale indifferent melt.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container][fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” hundred_percent_height=”no” hundred_percent_height_scroll=”no” hundred_percent_height_center_content=”yes” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” enable_mobile=”no” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=””][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ spacing=”” center_content=”no” link=”” target=”_self” min_height=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”left top” background_repeat=”no-repeat” hover_type=”none” border_size=”0″ border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” padding=”” dimension_margin=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=”” last=”no”][fusion_text]

Ginny Lowe Connors is the author of several poetry collections, including Toward the Hanging Tree: Poems of Salem Village. Connors has also edited a number of poetry anthologies, including the recently published Forgotten Women: A Tribute in Poetry. She is the editor of Connecticut River Review. Connors runs a small poetry press, Grayson Books. Visit her website at ginnyloweconnors.com.

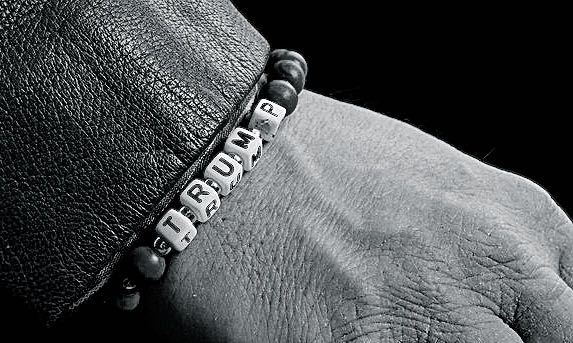

Image credit: Trauma and Dissociation via a Creative Commons license.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]