Wednesday’s Child

By Sara Marchant

On Wednesday, during peer review, a student waves me over to say something in a voice so low and hoarse I strain to catch the words.

“ICE went into Cardenas Market and took people away.”

“What?” I say. I must have misunderstood.

The students are reviewing papers with topics like Foucault’s panopticism, patriarchy’s rape culture, Snowden’s leaks, and The Hunger Game’s inversion of the love triangle. I have to rearrange my thoughts.

“ICE went into the grocery store and took people away. They were buying food and got taken.” He’s still whispering.

Abruptly, I’m sitting at the desk next to him. He raises his voice.

“People are afraid to buy food. Food.”

All the students go quiet. His words reach them, my selfie generation sweethearts. He looks around, uncomfortable with his new audience, then back to me.

“What are we supposed to do?”

What am I supposed to tell him? To say to all of them? Am I to tell him that I am as sad, scared, and confused as he? I stand up from the desk and address the entire class.

“What are we supposed to do?”

“Vote?” Crystal says.

I’d offered extra credit to anyone who registers.

“Do the shopping for people who can’t,” Reyna offers.

“Shop at the white people grocery,” Rigoberto throws in.

Everyone laughs, including our one white student, Penny. The rest of us in the class are people of color in our varying shades of not-white. We are anxious people, but united in our sentiment, our goal: What do we do when our people are targeted while engaged in activities of daily living? There are no answers, we decide, not yet. We promise each other to keep asking and trying.

• • •

On Friday, in another class, a student asks to speak to me privately. “You can walk with me to the copy center,” I say. Because we live in the world we do: As adjunct faculty, I don’t have an office. I’m not paid for office hours. I try never to be alone with male students.

We walk across campus and my student tells me he has to be absent the next week, for his work.

“Fine,” I say. “Keep up with the assignments. Nothing is due next week anyway.”

“Everyone thinks I’m a cop,” he says. “I’m not. I’m asking you to keep this between us because everyone in class hates ICE so much.”

I trip over nothing and, worried that he’ll try to assist me, take a sideways step so he can’t touch me.

“See?” he says, as if I’d said something or done something overt. “I need you to keep my job between us.”

Never mind that he doesn’t need to share this with me at all. I’ve forgiven his absence. Did he want me to forgive his profession as well? Perhaps because I am silent, he keeps talking.

“I’m not ashamed of my job,” he says. “I’m not a traitor to my people. I was born here. The illegals are not my people.”

“No human—” I begin from habit. I am not allowed to finish.

“I know, I know,” he says. “No human being is illegal.”

You’d be surprised how often my male students feel entitled to interrupt me. Unless you are a woman, then you’re not surprised at all but merely as tired of it as I am.

“If you’re not ashamed,” I ask, “why must it be a secret? When we are discussing the subject in class, why don’t you join in? Present another side for discussion? Another view?”

“Because everyone will hate me. My peer review group might kick me out. Or they’ll get that look on their faces.”

Like the one on mine.

“Don’t believe everything you see on the news,” he says. “Most of what they say isn’t true.”

“Did you just say that to me, your critical thinking professor?” Enraged, I draw strength from the anger. “Do you think I share anything in the classroom that hasn’t been vetted and verified? Have you not heard anything I’ve said about checking sources?”

“I apologize!” he says. “I apologize. I forgot who I’m speaking to and you’re right about one thing …”

One thing. I’m right about one thing.

“Every ICE office, every station, every television is on the FOX News channel. We’re not allowed to change it. You’re right about the feedback loop.”

We are almost to the copy center. It’s a beautiful Southern California day. The jacaranda trees are in purple bloom; the lawn is being mowed. There are hummingbirds strafing the rose bushes. Everything smells fresh and clean and safe. This interview is almost over. I can see the end in sight.

“If you know that much, can recognize that …” I don’t know where I’m going with this thought. Haven’t I told my class, his class, over and over, that you can’t argue against irrationality? There’s nothing to grab onto. When people aren’t capable of critical thought, arguing against their emotions is not only futile, but dangerous.

Now I’m thankful this student, this ICE agent, isn’t in my other class. I hope no one in this class, his class, has inadvertently let slip their undocumented status. I let my last attempt at a sentence go and start over.

“I’ll only keep your secret,” I say, “if you promise never to report on any student at this school.”

He looks genuinely hurt. I shrug at his pain. It’s good he should feel something. Even if it’s only for himself.

“I’d never,” he says. “And I’m about to graduate.”

This is cold comfort. We reach the copy center. In silence I make copies, in silence we begin the return walk. Why hasn’t he left me to walk back alone? More confessions are coming, oh lovely.

“My family asks me how I can live with myself. A Mexican man with an accent, no less.”

“Good question,” I say. I always praise good questions in my classroom, questions are the basis of critical thought, after all. And I’ll grant him no absolution.

“If 80 percent of the people I’m arresting are criminals and the rest are innocent mothers and fathers, I can live with that.”

Whatever he sees on my face stops him. There’s a woman’s restroom up ahead and I point to it.

“I’m going in there,” I say, “and you should go back to class.”

He turns with a martial pivot and walks away.

The restroom is empty and after I vomit I stand for a moment with the cold water running over my wrists. The second half of the class must be taught, my copies spilled on the bathroom floor need to be picked up. I have two hours until the privacy of my car and a good cry. Thinking about my mother’s Jewish family—were they innocent mothers and fathers or criminals?—doesn’t help me. Thinking about my Mexican father’s family—would my student consider them murderers and rapists?—only makes me angrier. What does he see when he looks in the mirror? I wonder as I look at myself.

Then I shut off the water, pick up the papers, and I return to my classroom. I keep his secret, he keeps his side of the bargain—as far as I know. I never look him in the eye again.

• • •

Wednesdays and Fridays pass by, two months of them. The school year ends; my students say goodbye. Every time I shop for groceries, I think of my Wednesday child. When Jeff Sessions orders the separation of children from their parents and ICE puts them all in different camps, cages and tent cities, I email my Friday child:

What happens when the innocent mothers and fathers and the breastfeeding infants become the criminals? What then?

He never replies.

Sara Marchant received her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of California Riverside-Palm Desert. Her work has been published by Full Grown People, Brilliant FlashFiction, The Coachella Review, East Jasmine Review, ROAR, and Desert Magazine. Her essay, “Proof of Blood,” was anthologized in All the Women in My Family Sing. Her novella, Let Me Go, was anthologized by Running Wild Press, and her novella, The Driveway Has Two Sides, will be published by Fairlight Books in July 2018. Sara’s work has been performed in The New Short Fiction Series in Los Angeles, California, and her memoir, Proof of Blood, will be published by Otis Books in their 2018/2019 season. She is a founding editor of Writers Resist.

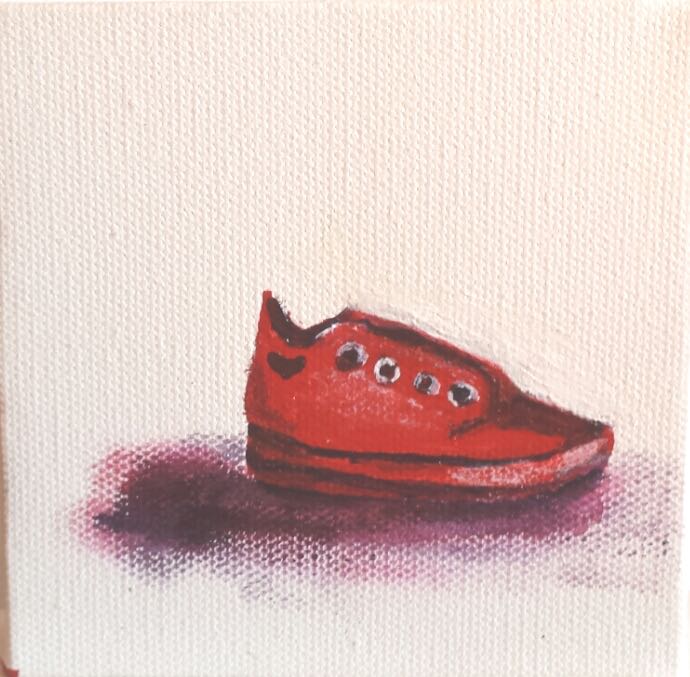

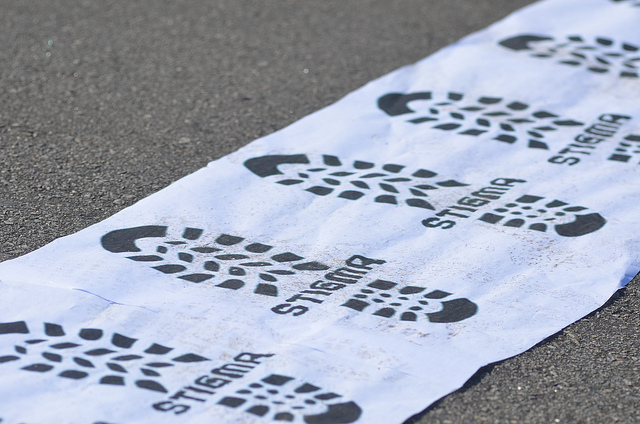

Art credit: ¿Donde Esta? by Laura Orem, a Writers Resist poetry editor.