French Kissed

By Angela Townsend

I went back to Frenchtown, but Frenchtown could not come back to me.

Frenchtown is the daintiest of the “river towns,” a flower crown ringing the Delaware. They hold hands across two states. They hold out bread for every stranger. Nothing snide can survive this soil. New Hope remembers its own name whether you are tourist or mayor. Lambertville will sling its arm across your shoulders. Stockton has never met an outsider. Frenchtown is counting the days until you come back.

Quakertown was landlocked, but it was mine. It was a freckle on the county seat, a guaranteed source of squished eyebrows. “Quakertown, Pennsylvania?” “No, Quakertown, New Jersey.” “There is a Quakertown in New Jersey?” “Yes. We can walk there from here.”

As long as we had a post office, we had Quakertown. We did not have much else. My apartment was attached to that post office, in an aging storybook house covered with murals and mistakes. Narrow stairs led to a spackled wall, and an oak trapdoor opened to the sump pump in my kitchen. My landlord, a meek behemoth whose head lifted the ceiling tiles, promised we would be safe. He forgot to pay the heating bill twice a winter, but “if civilization ever goes kablooey, we can hide under the door in the floor.”

I was happy and confused most of the time. I had come to Hunterdon County to practice my preposterous new degree, a Master of Divinity. But the Presbyterians itched with pox when I “talked about the love of God too often” with their youth group. I was likened to both Jezebel and the Sugar Plum Fairy. I was a twenty-five-year-old virgin who thought my job was to make everyone feel incandescent and safe. I took a job writing PR for a cat sanctuary.

I took myself to Frenchtown on Sundays, singing hymns from my childhood and yowling with Bruce Springsteen about God and sex and getting the hell out of New Jersey. I wondered if I might be a Quaker or an anarchist. I promised my mother I would text her when I got home, as she could not unclasp the fear of my death from her wrist.

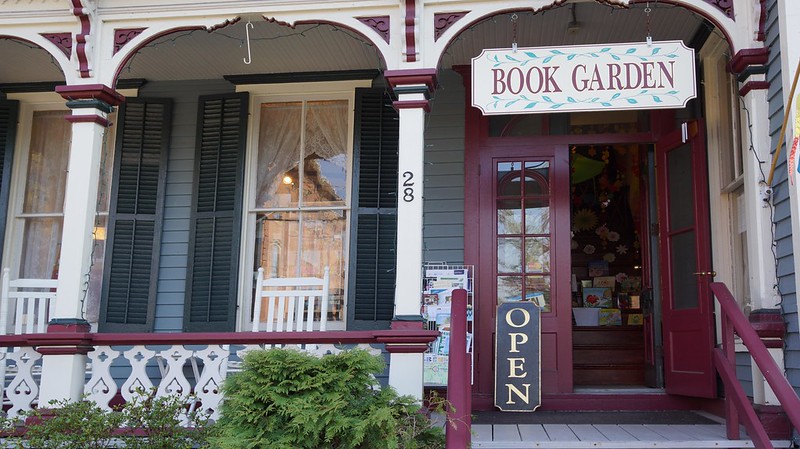

Frenchtown was ten minutes away, and it took me in. Glamorous, haggard women yarn-bombed the trees all winter, leaving limbs sweatered in magenta. Life-size porcelain horses appeared and vanished in front of the bank and the river, painted with gnomes or narwhals. The man at the book shop hid used arrivals for me, Bonhoeffer and Hauerwas. “You like your God fellas with lots of syllables.” When I stayed late, lights stringed the river like pearls so I could find my way home.

I did not mind being seen in Frenchtown. I wore gingham dresses and Eliza Doolittle hats. A Nikon jangled light around my neck, and I turned myself into a tendril to catch the light on the water and the foreheads. Strangers let me photograph their dachshunds and their plein air in progress. The woman at the Magick Shop called me a “precious little thing” in a way that made me feel larger. I wished her eight more lives. I took generic pictures of the river. I followed an exasperated stray all the way to a widower asleep on a bench. I did not doubt that I was a seer.

On July 14th, Frenchtown set fire to every contract with “cool.” Bastille Day was a chance to be as corny as a child. The town erupted in unauthorized innocence from the river to the lumberyard. Eiffel Towers were $3. Mimes on stilts blew bubbles. I saw a German shepherd dressed as a baguette. I saw God laughing so hard, God cried.

I etched Bastille Day on my calendar, setting annual reminders for the holy day of obligation. I acquired Eiffel Towers in colors not seen since Eden. I blew kisses at children on shoulders and men my grandfather’s age. They were singing hymns in French outside the Methodist Church. “We have been practicing for weeks,” a woman in a name tag whispered when I bought a lemonade. “La Grande Bertha” was wearing a beret so inflated, it resembled the Jiffy Pop popcorn foil. “I’m sure we pronounced everything wrong.”

“I pronounce you the jewel of Bastille Day,” I responded, and blew her a kiss. She kissed me on both cheeks, and we laughed until we nearly fell down.

I wrote a blog post for the cat sanctuary called “Find Your France.” I dressed the cats in stripes to make the point that “Paris” is anywhere you feel safe. I named our next impound “Jean Valjean.” I hid an orange Eiffel Tower in my boss’s lunch box. I was happy and confused.

A man from Philadelphia gave me a box of certainty. We married in two months.

The midpoint between his factory and my cat sanctuary dropped us in Bucks County, too far ashore to touch even New Hope with my fingertips. We found a second-floor condo. I wrote a story to supplement the lack of pictures.

He convinced me I had an excess of Eiffel Towers. If I wore bright garments, everyone would think I wanted them to look at me. I had to be careful with flowery language. He asked when I was going to discontinue my monthly donations to the manatee rescue and the radio station. I had to consider that God did not get involved with cats or weather. I had to stop talking to my mother so much if I wanted to finally grow up. I brought everything pink to work.

I turned forty and greeted him at the door wearing a rose fascinator. He asked if I was finally going to drink some wine. It was getting ridiculous to have never drunk alcohol at this age. I made it five more years.

Bucks County wasn’t Quakertown, but my landlord had died, and my long-haired cats loved the light on the second story. I would stay in Langhorne and send the man on a raft with just enough forgiveness to make it across. My mother arrived with such urgency that syntax collapsed. Her trunk was filled with calico pillows and a rose window sized for Notre Dame. My mother turned Langhorne pink.

I lived happy and confused among the cats in the clean condo. I wrote essays and courted rejection letters. I wore a blinding orange parka with a collar that looked like Elmo’s pelt. My Nikon hibernated as I turned to narrative. My language found homes in journals with names like Mollusk Family and Electric String Cheese. I exposed the image of God in people who send $10 checks to cat sanctuaries. I leaked secrets. A man across the Atlantic published my uncareful praise and asked me to come read aloud.

I told him I wished I could. He told me to picture the Seine giggling with “our community,” sharing “most excellent food and companionship.” I told him I wished I could. He said, “It is a shame, for your presence would illuminate the proceedings.”

I told my mother I was going to get that sentence tattooed on my ankle. She was still recovering from my tattoo of the cats, etched by a man named Big Mike in New Hope. I drove to Frenchtown instead.

I went back to Frenchtown. The teenager in the crystal shop asked if I’d seen the new amethysts. The boy surrounded by Frisbees saw my confusion and soothed, “You’re not crazy. This used to be Ooh La La.”

“What happened to Ooh La La?”

He wasn’t sure. His baseball cap was backwards. “But everyone still asks. It’s been five years.”

I bought a root beer and thanked him. The bookshop was closed, but proud to be “Under New Management!” There was no yarn in the trees. I took a picture of an Australian shepherd with my phone, but he turned his head. The pedestrian lane of the bridge was closed for maintenance.

The Methodist Church marquee said COLLECTING MEN UNDERPANTS FOR HOMELESS THRU 2/15. GOD IS GOOD ALL THE TIME. I drove home and wrote about it. Frenchtown could not come back to me, but we were both safe. I dreamed of lights on rivers and woke laughing aloud.

Angela Townsend (she/her) is the development director at a cat sanctuary. She graduated from Princeton Seminary and Vassar College. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Arts & Letters, Chautauqua, Paris Lit Up, Pleiades, and Terrain, among others. Angie has lived with Type 1 diabetes for 34 years, laughs with her poet mother every morning, and loves life affectionately.

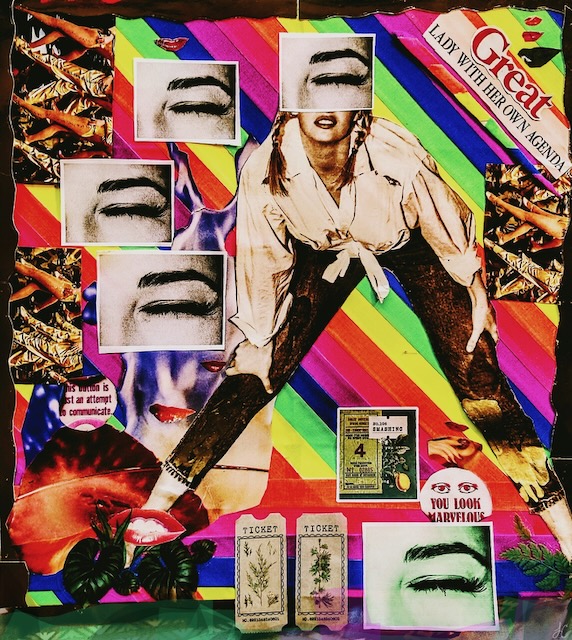

Photo credit: Regan Vercruysse via a Creative Commons license.

A note from Writers Resist

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.