Across the Hard-Packed Sand

By Holly Schofield

Kelly, the dispatcher, sent the call my way, but Nick caught it too, so my squad car arrived at the beach parking lot a few seconds after his. We hadn’t worked together much, but I’d sussed him out long ago. He wasn’t one of the good ones—those were rare—but at least he mostly pretended I was one of the team.

Unless money was at stake, of course. At five hundred dollars a pair, the toe bounty could be a lucrative second income for us cops. By the time I’d slammed my car door, he was racing ahead down the bank, skidding in the loose oyster-shell scree. “Watch your step, Allie,” he called back, his voice holding glee along with old-fashioned gentlemanly concern.

“Alaa,” I corrected automatically, wearily. He could have pronounced it right if he cared. But if he cared about stuff like that then I wouldn’t be running full tilt through the salt grass behind him, shovel in one fist.

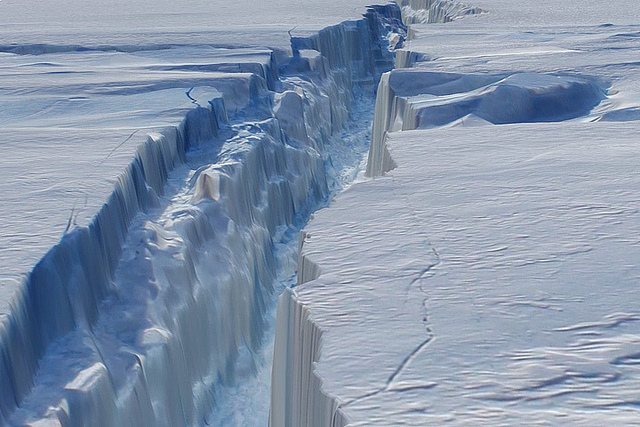

The sun struggled through rumpled chrome-colored clouds and winter still clung to the cold foam of the surf. Kelly had described the radar-tracked location pretty well, and it was easy to spot the dull blue of the shattered spacepod, the size of a bar fridge, way down the gray beach near a cluster of seaweed-streaked rocks.

I began to jog once I hit the hardpack. One foot after the other over this seemingly endless stretch of northern Washington coastline. Fleeing from Syria, sliding into America under the wire, becoming a naturalized citizen, qualifying for state trooper, my personal foot race never seemed to end.

And then the Veldars had come.

And kept coming. And coming.

Would there ever be a time that I could just stop?

Nick whooped, thin and reedy over the booming Pacific. He’d reached the crash site and was bent over panting, hands on knees. I wasn’t even halfway. I slowed, my bad knee flickering with pain, and walked parallel to the line of unidentifiable sludge that decorated the high water mark. No hurry now. I’d lost. And so had the Veldar.

Sunburned cheeks flushed even redder by victory, Nick waited until I approached then pointed behind the largest rock. “Hah! ‘Bout time I nabbed one.”

The shivering alien, slightly larger than most, squatted in the rock’s shadow, its face-tendrils dangling limply below earflaps. Translucent down to lean gray bone, the alien resembled a large jellyfish that had swallowed a miniature Halloween skeleton.

I avoided its eyes and jabbed the shovel upright in the sandy muck. “You win, Nick.” One kick with my bad leg and I sent some bull kelp sailing into the water. I told myself it was a relief that this Veldar’s life was out of my hands. Yeah, a relief.

The alien raised a stick-like arm toward us and let it fall. Did it know what Nick was about to do?

Nick was walking around the collection of boulders one more time, being cop-thorough. “Yeah, just the one of ’em,” he reported and dusted off his pant cuffs. An all-around typical statie, albeit a bit more fastidious than most. His shirt was still neatly tucked despite his run and his fake sandalwood odor indicated extra-strength deodorant.

Huh. Maybe I could work with that.

“Have fun,” I said. “Last time I shot a jellyrat this big, the guts stained my uniform. Even dry cleaning didn’t get it out.” I stepped back, ostentatiously. “I’ll just let you get on with it.”

He laughed uneasily. “Hey, five hundred dollars covers a lot of dry cleaning. And, remember, you officially caught this case so you get the paperwork. You can’t leave until you do the location sketch. Don’t try to weasel out.”

“Oh, shit, yeah, all those extra forms. Last time, I forgot one for Fish and Wildlife and the captain gave me hell.”

He grunted in faint sympathy, fingering his holster flap but not opening it. The Veldar’s various cuts and scrapes had left a trail of yellow-tinged slime as it had dragged itself from the spacepod to the boulder.

I snorted, as if it smelled bad, and took another step back.

“I might have a plastic sheet in my trunk.” Nick stroked his thin brown mustache.

I heaved a huge sigh, hoping I wasn’t overdoing it. “Tell you what. You get the toes, and I’ll dispatch the jellyrat afterwards. And, I’ll bury it. But only if you do all the friggin’ paperwork for me.”

A jerk of his head. “What, cut ’em off while it’s alive? Seems kinda cruel.”

“Shift’s almost over. You can get to Sweeney’s in time for Happy Hour. And it’s not like the ‘rats feel any worse pain than a cockroach or something.” I held my face tight, lifted my black leather shoe and kicked the Veldar in one of its knees, managing to mostly strike the clear rigid joint covering. It must have seen my quick double-blink because it instantly deflated into the muck and moaned like a ghul. I shrugged. “And I’m in no hurry. I don’t go to mosque until sunset.”

Nick grinned. “Deal!” He drew out his bowie knife and grabbed each of the Veldar’s heels in turn, slicing off the bulbous pinkie toes. The Veldar screwed up its many-wrinkled face and flicked its nictitating membranes but only moaned once more. My stomach knotted and I tasted bile but I held it in.

Nick stuffed the glistening toes in a sandwich baggie. “Next jellyrat gets called in, we can do this deal again, if you want, Allie.”

“Sure.” I began to dig industriously, my shovel sending gray grit, seaweed, and bits of charred wood flying.

He hastily jumped back. “Okay, then, I’m outta here.”

Between shovelfuls, I watched him trot away. I’d have to time the gunshot carefully.

The Veldar lay, knees drawn up, elbows jutting, clutching its bowling-ball belly—resembling the malnourished toddlers I’d lived with back in the Turkish camps. Drying gel clung to the two stumps on either side of its narrow feet. Tired, yellow eyes stared endlessly at nothing.

A few minutes went by. Nick should be almost to the parking lot and out of line-of-sight. I drew my pistol. The Veldar watched me carefully.

I aimed straight out into the ocean and squeezed the trigger.

The retort made the Veldar scoot back against the rock. I blinked twice at it, in reassurance. “Hang in there, little buddy.”

Communication via blinks weren’t enough for the next stage. I drew out my black-market English-Veldar phrase book and flipped through it. War. Run. Hide. Enemy. We humans might not understand the reasons behind other alien races invading the Veldars’ home planet, or how the Veldars could keep stealing motherships full of thousands of these spacepods, but we—well, some of us anyway—understood the fallout. In the tent camp in Turkey, Baba had sat me on his lap and massaged my shrapnel-scarred calf muscle as he pointed out words in his little green Arabic-English phrase book. Soldier. Injury. Lifeboat.

That memory was all I had left of my father’s own journey—he’d died of a heart attack on our second day in America. I thrust away the thought as I finally found the page full of greetings. Now to see which Veldar language of several dozen.

“Tern ka?”

A blank look. So it wasn’t Veldar III. I sighed. This could take hours and I didn’t have that kind of time. Maybe I should just drag it to the squad car without its consent. Like border guards had grabbed seven-year-old me. Damn it all, anyway! I kicked some more kelp and ran a finger down the page. “Tennin bran?”

One earflap twitched.

Familiar, perhaps, but not its native tongue. I flipped a few pages to related dialects. “Vronah kro?”

The Veldar’s cheeks creased in two directions. “Hrran, vo narhh, hrran!” Its opaque organ sacs vibrated in excitement.

Ah, that was it, then. I made a mental note to tell Kelly to tag this one as Veldar XII in the underground database. “Hnnnah kravv voolah” I pronounced carefully. Worry no more.

“Vrahhah?” it croaked out. By now, I knew that word by heart in several languages. Safety?

“Hrran,” I said with as much conviction as I could manage. Yes. It was sort of true. Kelly and I, and a few other folks scattered across the Veldars’ vast northwestern drop zone, tried awfully hard to make things safer. Sometimes, we succeeded.

The Veldar relaxed back against the rock, letting its tendrils go slack with relief.

The Band-Aids I fished out of my bra helped with the Veldar’s oozing abdominal cuts but they refused to stick to the gunked-up sand on its toes. Finally, I gave up and wrapped its feet in evidence bags. “There. Feel better?” I’d tucked away the phrase book so tone of voice—and a quick double blink—would have to do.

It stretched out three bulbous fingers, forming a pyramid. Another gesture I’d learned in the last few years.

“You’re welcome,” I replied. “Us refugees gotta stick together.” I half-smiled, feeling better than I had all day. Hey, maybe I could keep on doing this.

A few more minutes of shoveling and I’d mounded a plausible gravesite. Tonight, I’d drive to Everett in my truck with its special compartment and drop the Veldar off at a safe house. From there, it would begin yet another journey. “Here’s two English words for you.” I pointed down the coast. “Underground railroad.”

“Vrahhah.”

“Yup.” A cold, damp wind had sprung up and the clouds threatened rain. The folding shovel fit under one arm and I lifted my burden awkwardly with the other, bracing my bad leg against the base of the rock. The Veldar breathed its odor of burnt raspberries into my uniform collar and wrapped warm slick arms around my neck. I’d have to change shirts once I got to the car but I had a fresh one ready. I was used to that.

I hunched a bit to protect the Veldar from the wind, sucked in a deep breath, and began the long hike to the parking lot.

Holly Schofield‘s stories have appeared in Analog, Lightspeed, Escape Pod, and many other publications throughout the world. You can find her at www.hollyschofield.wordpress.com.

Photo credit: Ingrid Taylar via a Creative Commons liense.