Patriarchal Palaver and Politics

By Chinyere Onyekwere

Kpotuba sweated profusely as she climbed the ten dilapidated steps to Nigeria’s Independent National Electoral Commission notice board. She looked for her name on the sample ballot, and its absence shocked her, rendered her huge undulating body immobile. She fought back tears of humiliation when a group of certified male contenders snickered as they walked by. Staggering away heartbroken, she flagged down a taxi, wondered what her next line of action could be.

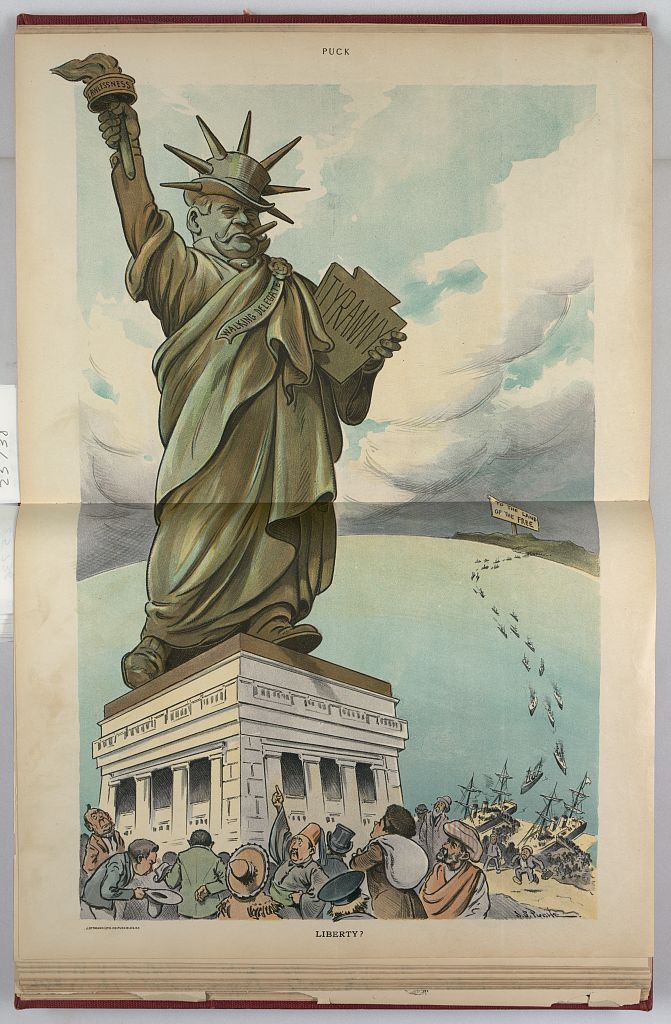

In her bid to vie for political office in her country Nigeria, the chairmanship post of Achara Local Government Area to be exact, she had unleashed the “Beast,” a deceptive, subtle cankerworm that had been allowed to fester and overrun the district. It marginalized her gender in politics, in virtually all spheres of women’s lives. Landmine navigation seemed like child’s play compared with her candidacy validation efforts with the electoral commission. The omission of her name from the ballot attested to the well-oiled machinations of the Beast; a calculated attempt to disenfranchise her from the chairmanship race because some of her country’s menfolk considered politics their exclusive birthright and domain.

Kpotuba heaved a sigh of exasperation and mulled over her first-time candidature woes as the taxi sped toward her abode. A born leader, Kpotuba burned with passion to make a difference within the squalid environs in which she resided. She organized women groups in her neighborhood, empowered long suffering families to alleviate their poverty-stricken state, a calamitous fallout from economic malfeasance by Nigeria’s political class. When the women spurred her to greater heights with a unanimous endorsement for her candidacy, the Beast reared its ugly head.

Unlike her politically savvy male counterparts, she was an unknown quantity, unversed in the art of campaign gamesmanship. When her candidacy was made public, the Beast bared its venomous fangs and sharp talons to bury her long-nurtured garden patch in tons of garbage. Before the effrontery of the assault could be digested, resounding gun blasts erupted in the vicinity of her home—warning shots to scare her out of the race.

They were messing with the wrong woman. The vicious acts had only strengthened Kpotuba’s resolve to defy the bunch of desperate, uncouth, rabble-rousing despots determined to derail her political ambitions. Patriarchal marginalization of the female gender in politics was an age-old, inherent culture passed down from generations of menfolk to keep women in their place. The Beast held sway in Achara district; women who kicked against it literally battled for their lives.

Even her husband’s support was lukewarm. Infuriated, she had rebuffed his salient but ominous “be careful” with her silence. Their once amicable relationship deteriorated to an exchange of monosyllables. Her grown children were indifferent, believing they were ignored by a country of failed promises and dubious future, so what did they care? Her political party contradicted its professed motto of equity, justice and peace to treat her with disguised incivility.

Her opponent, Anene Ibezim, the corrupt incumbent chairman of Achara Local Government Area, belonged to the ruling party. The perks of office lured him to perpetuate himself in power. He ran his campaign by resorting to vitriolic pronouncements with smug certainty of returning to office.

Months earlier, when Kpotuba and Ibezim crossed paths on the campaign trail, he stalked and sized up his adversary with a vow to banish any notions of political exploits harbored by the obese upstart of a woman.

“You’ll lose, fat cow,” he muttered under his breath.

“What did I hear you say?” asked Kpotuba, stopped her in her tracks by his barrage of words.

“What part of my sentence didn’t you understand. Lose or cow?” he asked.

“You belong in the kitchen!” yelled his ragtag entourage before they disappeared into the crowd.

She made an ignominious retreat, but with absolute conviction of his inevitable comeuppance.

When the taxi screeched to a halt, she was jolted back to the present.

The driver demanded his fare, double the standard price. “Why?” she asked, incensed at his belligerent tone. “Because you’re double the standard size,” he replied, eager to take off.

She alighted from the cab, closed the door with calm exactitude, and paused. A lifetime of imagined and real indignities coalesced into something sinister. She saw a blaze of hot fiery red and lost her head.

Her scuffle with the cab driver engendered comic relief for Nigeria’s pent-up populace; a welcome diversion from disillusion and despair. The fracas drew throngs of people, mostly women who cheered her on. The man, thoroughly terrified of being trounced by a woman, extricated himself from her grasp and fled. She let him escape, had no intention of crossing the thin line between mediocrity and madness to ruin her hard-earned political career.

She dusted herself off with an imperious stance and surveyed the crowd of women whose cries of adulation rent the air when they recognized her from posters advantageously positioned throughout the town. Kpotuba, struck by what could only be deemed divine inspiration, seized the moment with righteous anger to expound on the despicable acts of injustice, meted out to her by the electoral commission.

Her eloquent speech roused the bloodthirsty mob to a fever pitch. Her plight with the Beast became their collective outrage. Like a conjurer’s trick, the swelling masses metamorphosed into a full-blown protest march to do battle with the electoral commission’s perfidious lot.

Two weeks into the general elections, a political gladiator chose to bedevil Ibezim with a human trafficking scandal that rocked the nation.

Kpotuba won the election—with a landslide—to become the first woman in history to occupy the chairman seat of Achara Local Government Area of Nigeria.

*

A month later, hounded by the Crimes Inquiry Tribunal, Ibezim frantically packed up his personal items from the office. Startled by loud laughter, he reeled around to the menacing sight of a huge body blocking the doorway.

“Goodbye loser,” Kpotuba said.

Chinyere Onyekwere is a freelance graphic designer and a self-published author in Nigeria. Her passion for the written word won her Nigeria’s 2006/2007 National Essay Competition Award with her story titled “Motion Picture and The Nigerian Image.” Chinyere holds a Masters degree in Business Administration from the University of Nigeria. When she’s not glued to the computer screen, Chinyere keenly observes human conditions, and the state of the world in general, while trying very hard to not be hoodwinked by her mischievous grand twins. She’s currently working on several short stories for electronic submission. You can reach her at ockbronchi@gmailmail.com.

Photo credit: Courtesy of Bella Naija.

Laura is a poet, essayist and visual artist. She’s the author of Resurrection Biology (Finishing Line Press 2017) and the chapbook Castrata: a Conversation (Finishing Line Press 2014). Laura received an MFA in Writing and Literature from Bennington College and taught writing for many years at Goucher College in Baltimore.

Laura is a poet, essayist and visual artist. She’s the author of Resurrection Biology (Finishing Line Press 2017) and the chapbook Castrata: a Conversation (Finishing Line Press 2014). Laura received an MFA in Writing and Literature from Bennington College and taught writing for many years at Goucher College in Baltimore.

High above

High above