I Still Am

By David Martinez

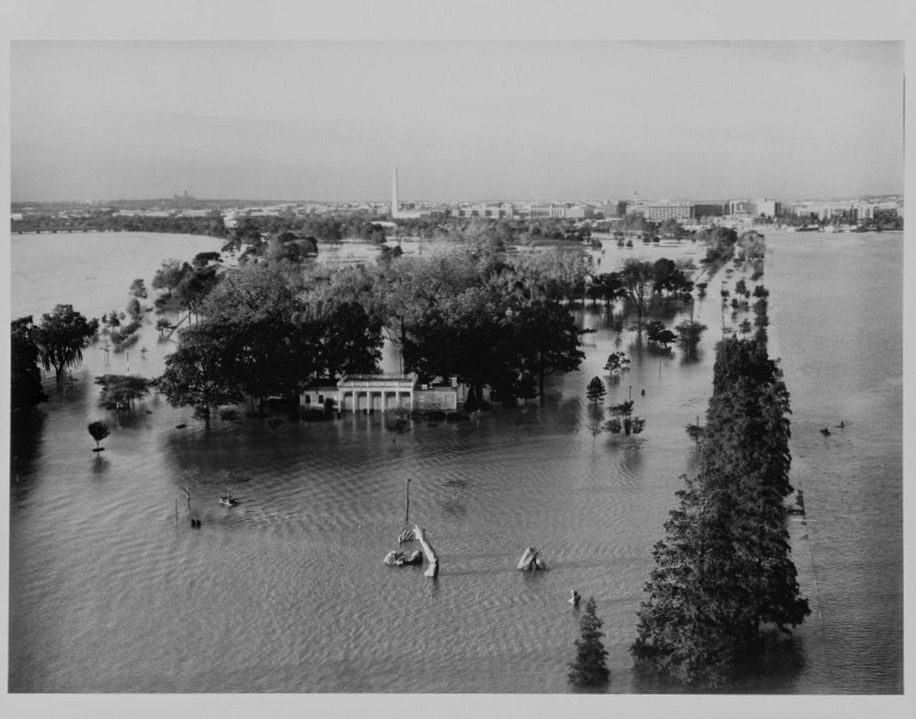

I’m reading Open Veins of Latin America—because I’m writing my South-American book—when the woman in the parking lot starts to scream. The man’s screaming, too, and it’s violent screaming and I can’t see them. But I know they’re both red-faced and she’s crying. She’s shrieking. They’ve both been shrieking for a lifetime, but I couldn’t hear them. Can only hear them now, like it’s a veil been lifted.

I go over to my apartment door and the noise comes in louder. The baby in the mix is wailing like he’s hurt. But I stand there and peek though the cracked-open door. I don’t want them to see me, because I don’t want them to go inside, because I don’t know what apartment they live in and closed doors are more dangerous than open ones, and apartments are more dangerous than parking lots. That’s what I tell myself, but maybe I’m just scared. I leave the door cracked, fall back in, and call the police. I’m terrified of police. But there’s a raging man and a raging woman and a baby, and I have no power, so I have to call.

What’s the emergency? The woman on the line says.

They’re fighting outside.

•

He’s my fucking child, the man says. He’s my blood.

There’s a slam against a car, a thud, a clamor.

•

Do you know the couple? the dispatcher asks.

No, I say. But I’ve seen them before.

•

The woman is pleading. The man shouts.

He calls her a cunt. He calls her a bitch. He calls her a whore.

•

Are you outside? the dispatcher says. Can you see them?

No, I say. I’m inside. But I can see the car and their heads. The guy is half in the car.

•

She sobs. She pleads. She yells, Get the fuck out of my car! You’re not right. Please, please get the fuck out of my car.

Another drunk thud and a splatter.

Yeah, he yells. Swing at me! Swing at me! I dare you, you fucking bitch. Think I won’t swing back?

No! No, please! I have a baby in my arms.

•

Sir, they’re next to what kind of car? the dispatcher says.

A grey one, I say.

And can you tell me, she says. Are they Hispanic? Are they Mexican?

They’re white.

I pace up and down. It’s tiring. It’s tiring to be on the phone with her. It’s tiring to hear the violence outside, and I think of the history of violence and of U.S. bombs and the whole world while listening to the woman talk on the phone. That viciousness is far, and this viciousness is near and pathetic.

I walk outside and see the woman. Her face is red. Makes her older. She’s in her twenties—I know, because I’ve seen her before—but she looks like she’s carrying forty years. The man runs up to an apartment. I can’t see him. He’s a shadow. She follows with the baby.

•

There’s a giant, white, Styrofoam cup shattered on the ground, and soda splashed and running into the asphalt—like blood—and the screaming on the street has died out.

•

I don’t remember walking onto the parking lot, but I’m here, and the group is still looking at the now-empty space where the fighting had been. There’s a guy on the phone with the police.

He knows more than me—watched them walk into the apartment. He knows where the violence is continuing.

As I walk by the group I hear, Mr. Martinez!

There’s a student here, and I can’t comprehend it because this is not a student’s place. Their place is in the classroom on the far side of town.

When I turn, there’s John surrounded by a small swarm of his friends, the most disruptive, funniest seventh-grader I taught last year. One who came from the reservation. One of the most problematic. One of the most hurt—with a sometimes abusive, sometimes apathetic mother, and a father he once told me he’d like to kill. One of my favorite kids.

But John isn’t supposed to be here. John is from a different life from over a year ago. John should be a dream.

Oh shit! I say, and I know it’s not the best greeting for an old teacher to give a thirteen-year-old, but it’s what comes out. What was all this? I say, thumbing toward the grey car and the poor remains of a struggle because I don’t know what to say or what to think or how to feel.

Some bitch about to get beat, he says.

He wants a response, and I want to tell him not to say that. I want to tell him not to talk about people like that, not to be sexist and mean. But he articulates it like he’s proud. Because he told me once that I’m one of his favorite teachers, one of the best he’d ever had, probably ever would have because he was going to drop out as soon as he could, because he wanted to shock me. He wants to prove that he’s bad, that he’s lost. I don’t say anything, because he wants me to, because he knows I don’t approve, because I know I don’t have to.

You’re still working over at the school, huh?

Yeah, I say. But I teach college now, too.

He needs to know this information, because sometimes people get to do what they want to do. He needs to know sometimes lives can work out all right, for a while. He needs to know that it doesn’t have to be like the lives of the students at school, where too many families are terrified of deportation and live in fear. The school whose kids have parents who threaten them not to talk about their abuse. The school that is in constant threat of losing its funding.

The cops show up.

One of the kids says, Hey, aren’t we going to my house? My mom’s not home.

We got to go smoke, Mr. Martinez, John says to me, and offers his hand. He doesn’t fist bump. He shakes my hand, then floats away into the swarm, moving toward the houses behind my apartment complex.

One of the neighbors, the guy who was on the phone with the cops, comes over to me and keeps talking about how he was just walking outside to go get a haircut when he saw the fight. Seemed pretty excited about it.

I had to get my brother and get out here, he says. My brother and I do mixed martial-arts.

Right, I say, and wonder if this is a guy who scares people back inside apartments, a guy who doesn’t know what to do with feral people, or a guy who does what he’s supposed to, who acted right.

His brother is nowhere to be found.

Who was that kid you were talking to? he says.

I don’t know why he cares.

He was my student last year, I say, pointing to the direction John and his friends went.

Yeah? he says. I’m studying to be a probation officer. He’d better watch out. He was saying some pretty nasty stuff over there. I’d like to show him and his buddies that being hooligans doesn’t pay. I’d straighten them out in a minute.

The neighbor points up at the cops banging on the couple’s door.

That’s what happens when you do drugs, he says.

His eyes aren’t level, like his skull is crooked.

Some chain-smoking woman with her stomach spilling from her tank top comes over and starts chatting with another neighbor. The crooked-faced neighbor takes off to get that haircut, and I see John again, close to another building.

•

John, I yell out. I don’t want him to go yet. I need to find words of wisdom. I have no words. But when I called him he stopped. Is this power? Is this responsibility?

So, I say. You live around here, then?

No, he says. I live down 75th.

John has the same bowl cut he had last year, crooked and cut badly in the same places. He looks the same. Still carries himself like he’s not part of his swarm, like he’s cooler, seen more shit, the way he did last year.

How’s things been for you, man? I say.

All right, he says. How’s everyone at the school?

All right, I say. You should watch out for those guys out there.

Shit, he says. They got to watch out for me.

Look, I want to say. Don’t be screwing around. You know you’re going to get yourself in trouble. I want to say something like that, but that’s not right.

Instead, I ask if he remembers that part he played in The Glass Menagerie last year in class. I had all the kids switch up for different scenes. He asked to play two scenes as Amanda. Thought it was funny.

Yeah, he says, and laughs. I remember everything from your class, and all them stories you made us read, and how you didn’t care when we cussed. That’s why we like you, Mr. Martinez. You’re not fake like the others. You don’t front.

He smiles wide, but this is not a joke and this is not what I want to talk about. This isn’t what I want to say.

Listen, I told you my brother’s in prison because of dope, right? I say.

I want to talk about the miracle of being alone and sober in an apartment, writing a book instead of on the hunt. But I don’t know how to say it.

Yeah. You told us. But my brother? he says and attempts to grin—as if he’s trying to act like he’s in a movie. My brother was killed because of shit I did, he says—says it like it’s nothing.

And since you last seen me I been to prison, Mr. Martinez, he says. For robbery. And I’m probably going to go back, too. I’ll probably fail my drug test.

Why? I say. What’s the point?

I don’t care, he says. Makes no difference.

What, I say. You like being locked up? You think juvey is fun?

Doesn’t matter, he says. In there. Out here. I got people inside. It don’t matter. I got shot since I last seen you, too.

You ain’t got shot, I say. Bullshit.

He might be lying. But it might all be true. At least he’s talking like it’s true.

I did, he says. I swear. Swear on my life. I did. I got shot. In the shoulder.

Okay, I say. Didn’t ask him to show me. He needs me to believe him. Whether it’s true or not, he needs it to be true, and he’s looking at me with those eyes. He wants to believe he has no faith in anything, because to think otherwise would crush him. There’s nothing else to be done. Nothing I can think of.

He used to call me Dad last year. Thought it was hysterical. I thought it was weird, and told him to stop.

I don’t think to give him my number, don’t point to my apartment and say something like, Anytime you need, don’t hesitate to come by. I don’t do anything like that.

I say, John, don’t do anything stupid.

You know me, Mr. Martinez, he says.

I know, I say. Don’t do anything stupid.

Before he leaves I say, You were always one of my favorites.

I still am, he says, and smiles. He disappears with his swarm down the streets where I always get lost, because all the houses look the same. The woman screams—muted—in the apartment above, and the cops are hammering on the door.

•

I have to leave to pick up my wife, and on the way home we drive toward the setting sun that catches fire in the desert—the great and terrible monster of the West—and it’s fine. We give ourselves to it, and all we can do is watch.

David Martinez has an MFA in Creative Writing from the UC Riverside Low Residency program in Palm Desert. He has dual citizenship between the United States and Brazil, and has lived in Puerto Rico and all over the United States. David has conducted interviews for The Coachella Review, and his fiction has been published in Broken Pencil. When he is not teaching at Glendale Community College in Arizona he substitutes in elementary and middle schools. David is currently working on his first novel.

Photo credit: Rennett Stowe via a Creative Commons license.