Enough

By Alyssa Beatty

I add another rowan branch to the fire underneath the brazier and test the water with my pinky. Almost hot enough. A quick count of the bundles of herbs on the kitchen counter to make sure I have everything I need. Rose-tinted sunset streams in through my back door, propped open with a cinder block. It’s a signal to anyone who needs me.

First in is Mr. Murphy, who needs a tea for his arthritis. I decant a measure of hot water into an old glass Coke bottle, sprinkle in the herbs, and seal the top with wax.

“Let it steep until you get home. Drink it all. It’ll taste like ass, but it will help,” I tell him.

He ducks his head in thanks, holding out a loaf of fresh baked bread from his wife. He’s never said a word to me, but he’s also never missed a visit.

When he’s shuffled out the back door, I sit at the kitchen table, waiting. I should turn the radio on, for the illusion of company. But it seems like too much effort to get up again.

I turn the little mustang figurine toward the door, letting him see the sky. He’s my reminder, for days like today when I’m feeling worn out, of why I’m here. Mustangs were brought to a place they didn’t really belong and made it their own so completely that they became synonymous with their adopted landscape. I don’t belong here either. I’m a city girl at heart, more at home with concrete and steel than the endless flat plains that surround this speck of a town.

Some people think witches shouldn’t live in cities; that they need to have their feet on bare earth, see the sky and hear the wind in the trees. But those people have never harvested the energy of a crowd at a street fair or bathed naked in the moonlight reflected off a skyscraper.

Before I start to feel too sorry for myself, Martha Sperry knocks on the door. I’ve told her a million times if the door is open, she doesn’t need to knock, but small-town politeness is ingrained in her.

“Come on in, Martha. Need a refill?” I rise from the table, trying to disguise my weariness.

“Yes, please, ma’am.”

Martha’s son suffers from the worst case of cystic acne I’ve ever seen. Poor kid’s face looks like a map of the moon. He’d never agree to treating it with what I’m pretty sure Martha’s husband calls “devil’s brews,” but my tea works wonders for skin conditions. Martha’s been slipping it into her son’s dessert every night, and he’s come so far out of his shell he asked a girl to homecoming. Small victories.

I stir the herbs into the hot water, carefully pouring the brew into a yellow Tupperware bowl. As far as her husband knows Martha and I have been swapping soup in this bowl for the last three months. She takes it carefully and pulls out a hand crocheted rose and gold shawl, the exact colors of the sky outside. She’s really talented. I can’t help but picture her at an artisan market in the city, selling her wares for a hundred bucks a pop.

I need to stop thinking about the city. I’m here now. I stroke my finger along the mustang’s side. I picked him up at a swap meet on the trip here. He’s inexpertly cast, the metal lumpy and undefined on one side. But some magic leaked into his legs; they flow, capturing the joy of motion. He looks free.

It’s almost time. I dim the lantern on the table. The next client won’t want me to see her face or know her name. I wish I could concoct a tea that would take her shame and lay it squarely onto the man who should bear it. Lay it so squarely it puts him in the ground. I close my eyes and take deep calming breaths, visualizing my mustang, hooves thundering on the earth.

She slips in so quietly, trying to make herself small. My heart aches. Even in the dim light I can see the bruise blooming on her jaw. There are other bruises, too, I know, hidden under her loose sweatpants and oversized hoodie. On her wrists. Her thighs. She can’t be more than sixteen.

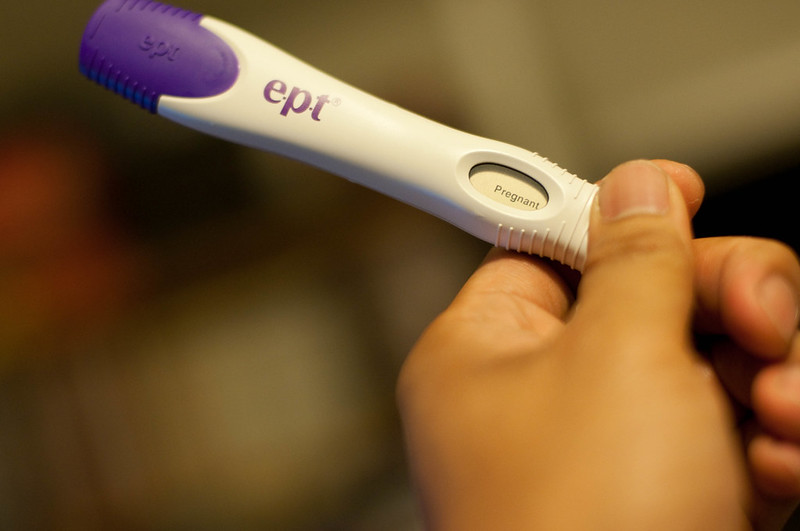

“Are you the lady they told me about? The one who helps . . . girls in trouble?’

“I am. Sit down. I’ll get started.”

“I don’t have money. The clinic . . . it used to be free.”

The clinic has been scorched rubble for two years now.

“I don’t take money.”

I scoop the water from the brazier with a jade cup, for peace.

“Will it hurt?” she whispers, as she watches me mix the herbs.

“Yes.” No use lying to her. “You’ll feel nauseated. You might throw up. And you’ll bleed. A lot. Drink ginger ale, real stuff, not Canada Dry, and rest as much as you can, until it’s over.”

“What will I tell my dad?”

There’s a lot of things I want to say to her father, none of them pleasant.

“Tell him you have the flu. The symptoms aren’t too far off. Burn or bury your pads, if you can.”

She nods, eyes downcast. Tears glimmer in the lanternlight.

“It’s not your fault, you know,” I murmur, filling the Coke bottle, melting the wax.

She clears her throat, taps her finger on the mustang’s nose.

“I like this. The way it looks like he’s running. Where’d you get it?”

“Someplace between here and San Francisco.”

“I’d like to go there, someday. Or anywhere, really.”

There’s no potion I can brew that will get her out of this town.

I offer her the bottle, and she slips it into her hoodie pocket. Just before she disappears into the night she whirls and hugs me, stick-thin arms around my waist.

“Thanks.”

I turn the lantern off. Starlight streams in; my mustang runs in their shimmer. I picture the girl running too, long legs skimming prairie grass, leaving this place behind. I picture it as hard as I can. Maybe it will be enough.

Alyssa Beatty lives and writes in Brooklyn, NY. Her work has appeared in Luna Station Quarterly, Flash Fiction Magazine, and Spread: Tales of Deadly Flora. Find her at alyssabeattywrites.com.

Photo credit: Madhu Madhavan via a Creative Commons license.

A note from Writers Resist

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.

You bungee-cord the poster to a tree and take your position between the clinic entrance and the parking lot. You’re armed with the assurance that you’re doing God’s righteous work, as Mother taught you, witnessing for life, sidewalk counseling would-be abortion victims, guiding them away from mortal sin, toward salvation. You adjust the bunched-up layers around your waist while you await the poor misguided mothers, bearing their precious preborns to slaughter. You know they will come, as they do every week, in numbers that torment your heart with the horrid image of God’s beloved innocents torn asunder by evil and torturous tools in the hands of Death’s doctors. But you are stalwart, determined to rescue a life from the great abyss of immoral destruction.

You bungee-cord the poster to a tree and take your position between the clinic entrance and the parking lot. You’re armed with the assurance that you’re doing God’s righteous work, as Mother taught you, witnessing for life, sidewalk counseling would-be abortion victims, guiding them away from mortal sin, toward salvation. You adjust the bunched-up layers around your waist while you await the poor misguided mothers, bearing their precious preborns to slaughter. You know they will come, as they do every week, in numbers that torment your heart with the horrid image of God’s beloved innocents torn asunder by evil and torturous tools in the hands of Death’s doctors. But you are stalwart, determined to rescue a life from the great abyss of immoral destruction.