At Heaven’s Door

By Christa Miller

After ten days of scavenging around the houses in our subdivision, I know it’s unsustainable.

Zoe and I had started with the houses next door, then worked our way down the street, but we were walking farther and farther for less and less.

I decide to head for Myrtle Beach, but Zoe doesn’t want to go. She’s worried about running into more mobs. I tell her, “They’re mobs, not zombies,” but my words fall flat. The memories in her dark eyes reflect in my mind: the way they banged on our door, broke our windows, searched the house.

I haven’t been able to tell her why they came. I’ve never been an open book, and my stepdaughter is as much a stranger to me as I am to her. She was 12 when I met her, 13 when I married her mother. Zoe had been deep in the throes of puberty-driven issues, and I’m sure it doesn’t help that I’m white.

When I finally convinced her it was time to hit the road, I expected it all to start up again: the thrum of National Guard Chinooks, the bizarre scenes of mob violence, the screams and gunshots that made us barricade ourselves in our home, our prepper stash enough to sustain us for six weeks.

But the streets are eerily quiet now. The sounds are long gone, along with the people who made them. Did they all leave? Move with their mobs into other communities like schools of fish, flow into the Lowcountry like floodwater? Or did they all give up once the mob lost its meaning and they came to their senses, go inside their houses to starve themselves or take pills?

I don’t know which thought unsettles me more. But I’m glad I made the decision to go on foot, just a pair of backpackers. I don’t want to draw any more attention to us than we already have.

On the road, my memories are so strong that, as we search stores for food and clothes, I nearly hallucinate perky greeting girls and tired middle-aged clerks, asking if they can help me find something. I catch myself with my eye out for store detectives following Zoe, or well-to-do white women eyeballing her clothing choices at checkout like she doesn’t deserve the moisture-wicking sports gear or new pair of Nikes. That’s why, at a truck stop off the interstate, I don’t even notice the trucker drawing down on me until he screams something about this place being the domain he’s taken for himself. Blinking, my head still full of distracted thinking that the place should have bustled with crying children and cranky clerks and zoned-out drivers, I turn and face the black hole of his muzzle and think, This is why I left my guns behind. I’d almost welcome the bullet.

When the glass display case full of little crystal figurines crashes down on the trucker’s head, I don’t comprehend what’s happening right away. That big old burly white guy lies there screaming, a thousand tiny cuts from pink tinted glass all over his face and neck and eyes. Then there’s movement in my upper peripheral vision, and I turn my attention there.

It’s Zoe, of course. My stepdaughter has gone above and beyond what I deserve.

We grab up as many snacks as we can carry and hustle on our way. Zoe doesn’t exactly walk with me, but she doesn’t disappear either. She has this way of sort of eyeballing the space around her until she sees that I’m in it. Then she keeps going.

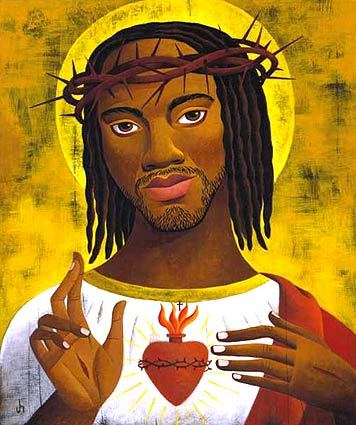

After the truck stop, there’s nothing but forest and farmland. By now, despite crazed white truckers, we’ve worked out that most everyone is gone. Disappeared, like the Rapture was a real thing, and we were the only sinners who didn’t get taken up. I don’t really think so, of course. Occasionally, holed up in a garage or shed, we’ve had to endure that sweet smell when it wafted on a breeze. Not often enough for suicide to account for all the disappearances, maybe more people died in the mob riots, but there’s no way to tell.

We manage to steal a truck from a farm and we drive just past Sangaree before it runs out of gas. It’s only been about an hour, and we’re a lot closer now to the coast, but the thought of walking makes my legs throb. Zoe, too. I can see it in her stiff limbs, the way she picks up her feet and puts them back down: gingerly, like she wishes the hard ground weren’t there.

We haven’t spoken since the truck stop. Time to give conversation a try. “We’re so close. All I want right now is to stick my feet in the surf.”

She shrugs, pushes her long box braids back away from her neck. “I’d settle for a place to stay and relax.”

“With a nice sun porch,” I try. “A hammock.” I chance a look at her face and catch the tail end of her eye roll.

We’re in a small community just off the highway. Zoe gestures at a little ranch. “No place matters if we don’t have food and water,” she says.

We have plenty, so much that I’m afraid any more will slow us down, but, whatever her reasons—probably a general disdain for my incompetence—Zoe seems to want the responsibility for scavenging.

The optics of a white cop letting a Black kid break into houses aren’t lost on me. After what happened to her mother, it feels like I’m setting her up for certain death. But arguing with her feels like an assault on her individuality, and so I watch her slip, cat-like, into the dark gap beneath the garage door.

Was Zoe into urban exploration or was it something she’d picked up from her video games? Jaye had never said anything about it. Jaye wasn’t a permissive mother, but she wasn’t strict, either. “Zoe’s like a river with a fast, deep undercurrent,” she told me once. “Damming it is only temporary, and you’d best have a way to relieve the pressure when it rains too hard for too long. Better to direct it. Set its path in the direction you want it to go, and hope it doesn’t overflow its banks.”

I could only wish I’d been raised that way. I might’ve gotten into less trouble. At the time I’d been excited that maybe Zoe and I had more in common than I realized. Now I think spit-and-polish discipline has been a part of my life for too long to be helpful to either one of us. All I know is, these urbex skills of hers, however she came by them, are exactly what she—what we—need to ensure our survival in this new world.

I come to a stop almost in front of the house, where I can see and hear anything that might go down, but I don’t go inside. That would be a good way to get myself hurt or killed if I were to turn a corner and surprise her, or anyone else who’s in there. Instead I wait. I keep my pack on my back and do a slow 360-degree turn, because I haven’t looked behind me in a while and I want to get my bearings.

As always, there’s nothing. A few high cirrus clouds tell me rain might be on its way, but that’s about it. There are no sounds, not the chatter of children playing nor the whir of lawn equipment. No footfalls or the squeak of a bicycle to tell us someone followed us. The air is flat and still, heavy with moisture and heat that won’t rise, and I suddenly have the irrational thought that we should be heading inland, away from the coast, because it’s hurricane season and what if? We’d never know until it hit us.

I shut it down. It would take us days to retrace our steps, and as bad as inland flooding has been in recent storms, we’d still have no guarantee of safety. I’d rather stay, maybe in a house built up on stilts, than risk fleeing.

Another five minutes and Zoe comes back out. She rolls her eyes again. “Why are you waiting for me?” she demands.

“Basic safety. Watching your back. Would you rather I went in there with you?”

She clicks her tongue and suddenly I know: Someday, perhaps sooner than I think, she’ll walk off without me, decide she’d rather just live on her own. I’ll wake up one morning, and she’ll be gone, or she’ll roll right out the back door of one of these houses and keep going, disappear for good.

I force myself to breathe, focus. Her hiking backpack doesn’t look any more stuffed than it did before. I resist the temptation to go in and do my own search, and instead I ask, “What’d you find in there? Anything good?”

She relaxes, just a little bit. “Nah. Those people took everything. Shelves were empty.” She hesitates, then meets my gaze. “Where are our photos?”

It takes me a few seconds to understand what she’s asking. The shame compounds tenfold when I realize I didn’t even think to bring any of the pictures Jaye printed from now-unreachable servers.

We halt in the middle of an intersection. Gas stations at opposite corners, a McDonald’s on one side, a Rite Aid on the other. All of them surrounded by weeds.

“How could you forget?” Zoe’s soft alto turns harsh, guttural. Her brown eyes meet mine, then slide away. Her mouth compresses into a thin line on her delicate face, and she twists a thin braid around her finger. “It’s not like we had no time. We spent weeks at home, waiting for the riots to blow over. Weeks. Plenty of time to go through the photos.”

What she’s saying is that those memories meant more to her than they did to me, and I’d never even stopped to consider that. I realize two things: one, I’d long ago reconciled with the idea that I might lose Jaye—you can’t both be cops and not recognize that—but I’d thought of Zoe as an extension of her. And two, I hadn’t thought—really thought—that we were truly leaving everything behind, but it pissed me off that Zoe blamed me when neither one of us had been able to think straight. I say the only thing I can think of to say: “If they were so important, why didn’t you go through them?”

She rocks back on her heels like I physically hit her. Then she takes off running.

Shit. Shitshitshit. The one thing Jaye would’ve entrusted to me, and I’ve fucked it up.

I stay in the same spot in that intersection for much longer than I tactically should. When Zoe doesn’t come back, I go looking for her.

What will I say when I find her? I don’t know. She probably won’t let me hug her. I’m so pissed off and frightened and ashamed that what I really want is for her to see me and follow me. To prove she didn’t just stick with me because she felt somehow compelled to.

I hear footsteps behind me, and my mind starts to play havoc. What if it isn’t Zoe, but some half-crazed resident, looking to loot me or worse?

The thought of being assaulted and left for dead out here in the street, under the baking Carolina sun, is what makes me finally spin around, hand at my hip where my gun used to be.

Zoe stops dead in her tracks.

She’s tied her braids into a ponytail, so it takes me three beats too long to recognize her. The first thing I notice is her expression: fearful, astonished, and, worst of all, betrayed. She eyeballs my hand until she’s sure I’m not really carrying. Then she seems to melt into the landscape.

I didn’t think the shame could get any worse, but it does. It burns my face along with the sun. I just made the worst possible assumption, not only about the only other living human being I’m aware of, but Jaye’s daughter, for fuck’s sake. And now I’ve chased her away, and the two of us are worse off for it. “I’m sorry,” I call out to the deserted street. My voice thin, weak.

She doesn’t respond.

I could end this all right now, one way or the other, if I could just tell her what happened to her mother.

She deserves that from me. They both do. I should have told her.

I take a deep breath, channel my most authoritative voice. “Zoe,” I call into the silent street. “Remember when we had to hide in the attic last month?”

No answer. But I wasn’t expecting one.

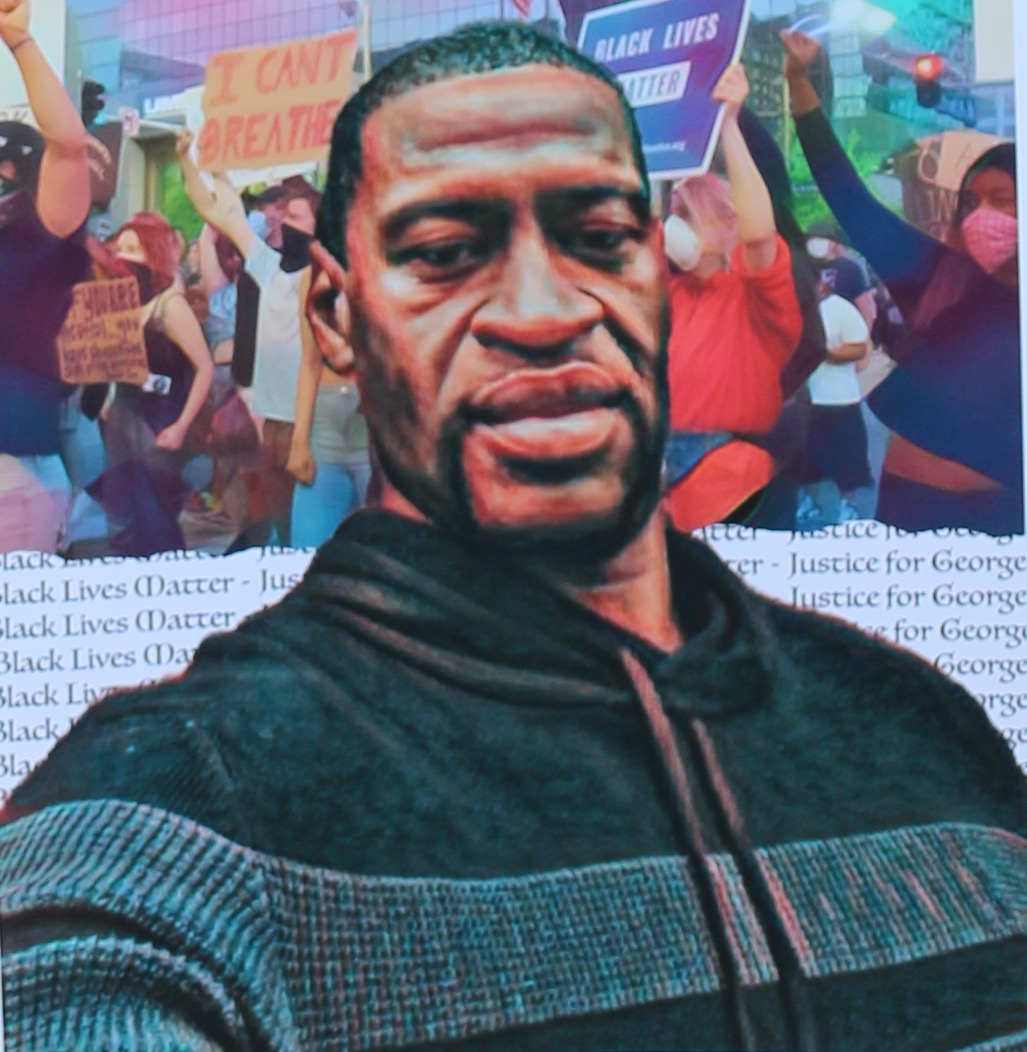

“I never thought I would ever have to do that,” I continue, “hide from people I considered friends, brothers even. But after what they did to your mother. … She tried to make them stop. They’d whipped themselves into a frenzy, thinking a group of unarmed civilians was looting a store, and she got in front of them. I couldn’t get to her in time. I promise you, Zoe, if I’d had any chance— In that moment, you were all I could think of. That moment … I’d been seeing for days, weeks, even months, who those people really were, but I couldn’t accept it until I saw what they did to their sister officer. Until I couldn’t say what they’d do to you. We were our own mob. The damage we did or were complicit in. So I deserted.”

Zoe sidles out from behind a parked car. I don’t give in to the relief. Not just yet.

Then she says dryly, “And you used to worry that video games were desensitizing me to violence.”

I have to let out a bark of laughter, because she’s right.

She doesn’t laugh with me, but her face softens. She hefts her pack on her back and without another word, starts to walk once more. East, of course.

I follow her.

Too goody-two-shoes for the rebels and too rebellious for the good girls and boys, Christa Miller writes fiction which, like herself, doesn’t quite fit in. For nearly 20 years, Christa has written in genres ranging from crime fiction to horror to children’s, but prefers to write—and read—blended-genre stories. Her affinity for the dark, psychological, and somewhat bizarre doesn’t stop her from volunteering at a local wildlife rescue, adventuring with her two sons in rivers, swamps, and marshes, or—when she’s not running her freelance business—relaxing with a book and a beverage in her hammock. Learn more at her website, christammiller.com.

Photo by Donovan Valdivia on Unsplash.