My Last Teacher Said My Thesis Doesn’t Have to Be a Sentence

By Yennie Cheung

Bullshit.

I call bullshit. It is bullshit that your last teacher ever said this, and bullshit that you think I’d ever believe that anyone who has ever assigned an essay in the history of essay-assigning would say that a thesis statement can be anything but a sentence. One sentence. Not a paragraph. Not a dependent clause. Not some miasma of an idea drifting in the negative space between words like participial fairy dust. It is a sentence—the single most important sentence of your entire paper.

I have said this to your class thirty-six times in the last two weeks.

So, of course, you chose to wait until half an hour before your paper is due, interrupting my sad sack of a sack lunch, to ask for help writing your introduction—an introduction you should’ve completed last Friday, when your paper was originally due. But instead of turning it in, you asked for an extension and went to an away game with the frosh football team. And you couldn’t even play. Because you forgot your uniform. In my classroom. Last Tuesday.

I think we can agree, Jimmy, that that is some bullshit.

And I know it’s blowing your mind that your English teacher just said the word “bullshit” to you. I’m not supposed to say things like that, which is weird because I’ve heard the football coach call you a crusty bitchzipper and make you do burpees until you puke, and everyone’s cool with that. But my calling you out on your bovine diarrhea means you’ll go whining to the principal, who will drag me into his office to mansplain the various ways I could’ve deescalated this situation so that he won’t have to hear your parents scream viler obscenities at him over the phone. This whole conversation will be brought up in my performance review, which will cost me my shot at tenure, and then I’ll be fired—all because you had the audacity to blame your previous teacher for your refusal to follow directions.

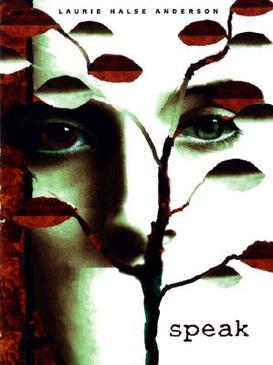

And do you know who’ll be extra happy to see me go? Richard Scroggins from the school board. See, last year Dick Scroggins tried to ban a book on the core curriculum about high school bullying and rape—a book so moving, it makes even frosh football players cry. Yes, Jimmy, I did see you wipe away tears when we finished the book two weeks ago. And no, you shouldn’t be embarrassed by that. It is dreadful, the way those students ostracize the main character. It’s unconscionable what that boy does to her when she’s alone and vulnerable.

So I know you’ll agree that Dick Scroggins was bat guano crazy when he claimed that the mention of rape in the book is tantamount to child pornography. That’s right: He called the book porn. Now imagine the exquisite shade of bruised plum he became when I suggested in front of the entire school board that he must be one kinky, depraved bastard to equate the assault of a teenage girl to sexual entertainment.

Jimmy, I know that you know better than that sanctimonious blowhard. You understand this beautiful, heartbreaking, not-at-all-pornographic book because, unlike Dick, you’ve read it. You’ve been changed by it. I see it in the way you look at your classmates now, wondering who else might be hurting. I see it in the way you glared at your teammate when he cracked that sexist joke in class, just hours before you “accidentally” clotheslined him during football practice.

But you can’t take them all down on the field. That’s why I assigned you an essay on the book. That’s why I’ve explained thirty-six times in the last two weeks how to form an argument with evidence and logic, not hearsay and excuses. This is why I’ve pushed you to put one solid, solitary thesis sentence in your introduction so people can easily locate your main idea and believe you when you tell them that being devastated for a fourteen-year-old rape victim is not sexually titillating. Because if I get fired, Jimmy, I’m not going to be here to defend the books you don’t yet know you love. I’ll need you to do it for me. I’ll need you to not be a goddamn Dick.

Yennie Cheung is the co-author of DTLA/37: Downtown Los Angeles in Thirty-seven Stories. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from UC Riverside-Palm Desert, and her work has been published in such places as The Los Angeles Times, Word Riot, Angels Flight • Literary West, The Best Small Fictions 2015, and The Rattling Wall anthology Only Light Can Do That. She lives in Los Angeles.

Cover art of multiple award-winning novel Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson.