Diet Margarita

By Terry Sanville

Douglas climbed the outside stairs two at a time to his second-floor apartment over Tuck’s Liquor. He keyed the front door and slipped inside. Fugem dropped onto the carpet from her window perch and yowled, then purred when he filled her bowl with kibble.

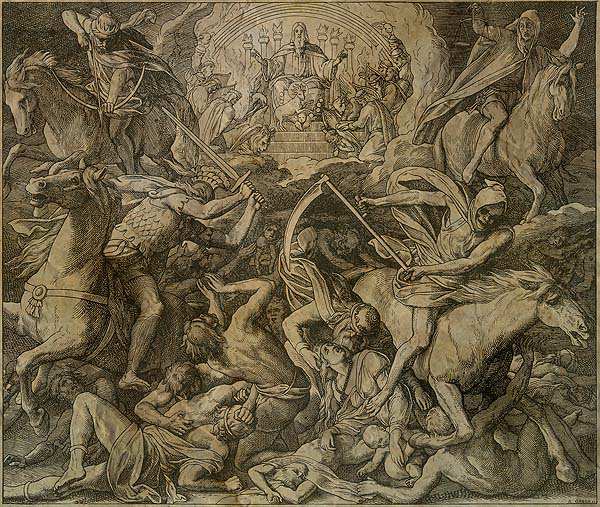

Outside, the noise died back, only a few screams or cracks of small arms fire, but the grenade blasts continued. They seemed to come from beyond the cemetery near Linden Avenue.

“How’s my kitty?” Douglas cooed and scratched the calico behind the ears. The cat arched her back until what sounded like an RPG landed somewhere close. Fugem fled to the bedroom and hid under a dresser full of clothes and ammunition.

Douglas smiled, dumped his knapsack onto the sofa, and went into the kitchen. From a drawer he removed a slender knife, grabbed two limes, a lemon, and a small orange from the fridge and laid them on the cutting board. He’d spent half his salary already, mostly on booze, ammo and cat food.

He poured the freshly squeezed citrus juice into a tall glass, added a very healthy shot of cheap tequila, three packets of artificial sweetener, and topped the drink off with soda water and ice. He stirred the concoction with his finger and raised the glass to his lips, but his nose caught the faintest whiff of tear gas. He knew that smell from the troubles the previous year, when a crowd of embittered seniors tried taking over a Walmart during the COVID-42 scare.

He set his drink down and dashed across the room to the window that looked onto the street. He’d left it partway open to allow air for Fugem. Pulling it shut, he reached into a cabinet, grabbed a roll of duct tape, and sealed the space under its sash, then drew the curtains back.

East Flatbush spread out before him. From over the cemetery a white cloud drifted toward his apartment. He moved to the hall closet, grabbed his Vietnam-era gasmask and retrieved his margarita. Lowering himself onto the sofa, he found the remote and turned on CNN. A bearded commentator pointed to a map that showed territory occupied by the Geezer Liberation Army (GLA) and the inroads they’d made throughout New York City, with Flatbush being one of several hot spots. The harried newsman stared into the camera holding a microphone that looked like a president-sized dildo.

“This just in. Factions of the GLA have ransacked a New York National Guard Armory. Cases of AR-15s, RPGs, ammunition, and other explosive materials were taken.”

Douglas sniffed the air then took another gulp of his diet margarita, the tart liquid clearing his mouth and throat of any nasty germs. He changed channels until a soccer game between Botswana and Brazil filled the screen. The teams played to an empty stadium. He sipped his drink and decided to phone Sharon to have her come over to help him with his calculus homework.

“Hey Shar, whatcha doin?”

“Just got home from campus. Don’t know why I go there anymore.”

“Yeah, me either.”

“It got nasty on the subway. Half the seniors were packin heat.”

“Hey, they’ll be gone soon enough.”

“Yeah, including my Grandmother, you idiot. I love that old gal.”

“Whatever.”

“Have you been drinkin already?”

“Yeah. Don’t worry, I’ve saved some for you.”

“Can’t come over tonight. Streets are too weird, could get picked off.”

“Want me to come to your place?”

“No, stay put. We’ll see what it’s like tomorrow.”

“But that’s when my calculus assignment is due.”

“Ah, and I thought you cared about me.”

The signal died and Douglas groaned. He phoned Sharon back, but she didn’t pick up or respond to his texts or emails. He polished off his margarita and fixed another. The soccer game bored him so he returned to the 24/7 news channel, where the commentator droned on with old material.

“The violence started when the federal government announced it would no long support efforts to treat or eradicate the coronaviruses. According to Vice President Puntz, ‘The best way to protect Americans is to let the virus run its course and allow the populace to develop herd immunity.’ This policy has drawn fierce reactions from seniors and their advocacy groups since only relatively young and healthy people can achieve herd immunity. The violence increased after the president tweeted that the high cost of Medicare required cuts to—”

Douglas turned off the TV and slouched in his seat. He wondered how the GLA had organized so quickly. Maybe those longhaired Vietnam vets finally had enough and decided to stick it to the man. His own grandparents supported the president no matter what the idiot did.

A grenade blast sounded close, near the police station or maybe CVS Drug, and the pop-pop-pop of small arms fire forced Douglas out of his seat. He staggered into the kitchen, fixed another diet margarita, and headed to his bedroom. From a bottom drawer he retrieved his Glock and several full ammo magazines.

He edged toward his front window and stole a glance outside. A ragtag squad of armed men and women, some of them in wheelchairs, cut an erratic path down the avenue, firing at houses, businesses, and especially at anything publicly owned. They ransacked Tuck’s Liquor Store below him and continued to move on.

Douglas crept to the door and slipped onto the outside landing. His Glock raised, he braced an arm against the railing, and fired, emptying the magazine, then another, and another. The street went quiet.

Breathing hard, Douglas smiled and ducked inside, returning to his couch and his margarita. He collected his laptop, to see what other news services were reporting. Lifting his glass to his lips he noticed a red laser dot in the center of his chest. Where the hell did they get sniper–

Fugem scooted from underneath the dresser and trotted to Douglas’s lifeless body. She lapped at the tart liquid splashed across the coffee table. She’d have something other than kibble to eat for days to come.

Terry Sanville lives in San Luis Obispo, California, with his artist-poet wife (his in-house editor) and two plump cats (his in-house critics). He writes full time, producing short stories, essays, poems, and novels. His short stories have been accepted more than 370 times by commercial and academic journals, magazines, and anthologies, including, The Potomac Review, The Bryant Literary Review, and Shenandoah. He was nominated twice for Pushcart Prizes and once for inclusion in Best of the Net anthology. His stories have been listed among “The Most Popular Contemporary Fiction of 2017” by the Saturday Evening Post. Terry is a retired urban planner and an accomplished jazz and blues guitarist—he once played with a symphony orchestra backing up jazz legend George Shearing.

Photo by Erika on Unsplash.