Impressions of the USA

By Cong Tran

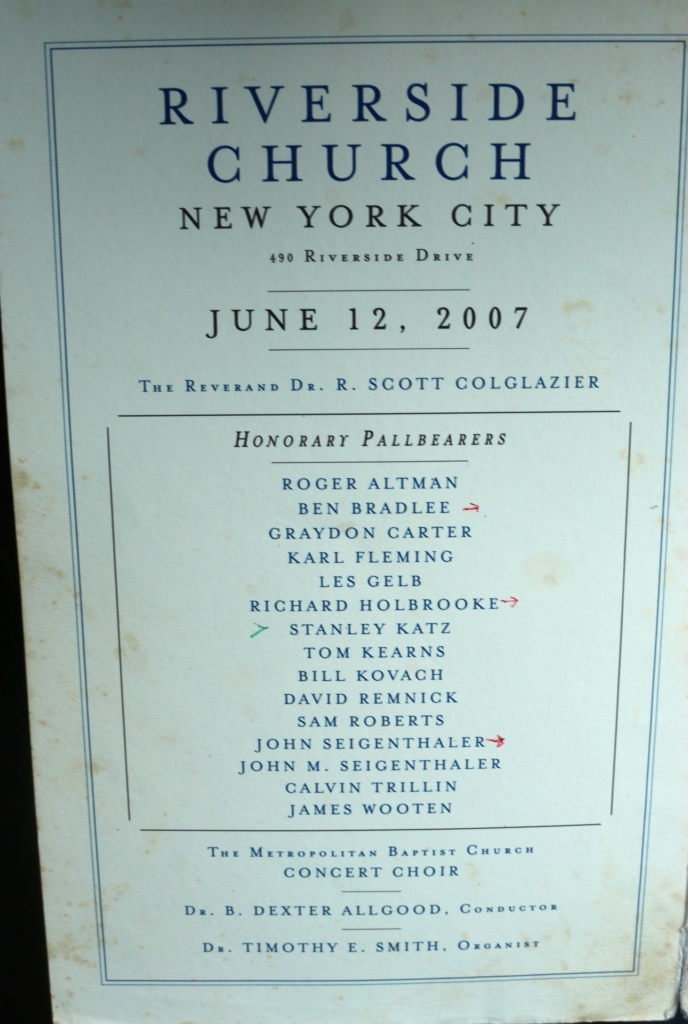

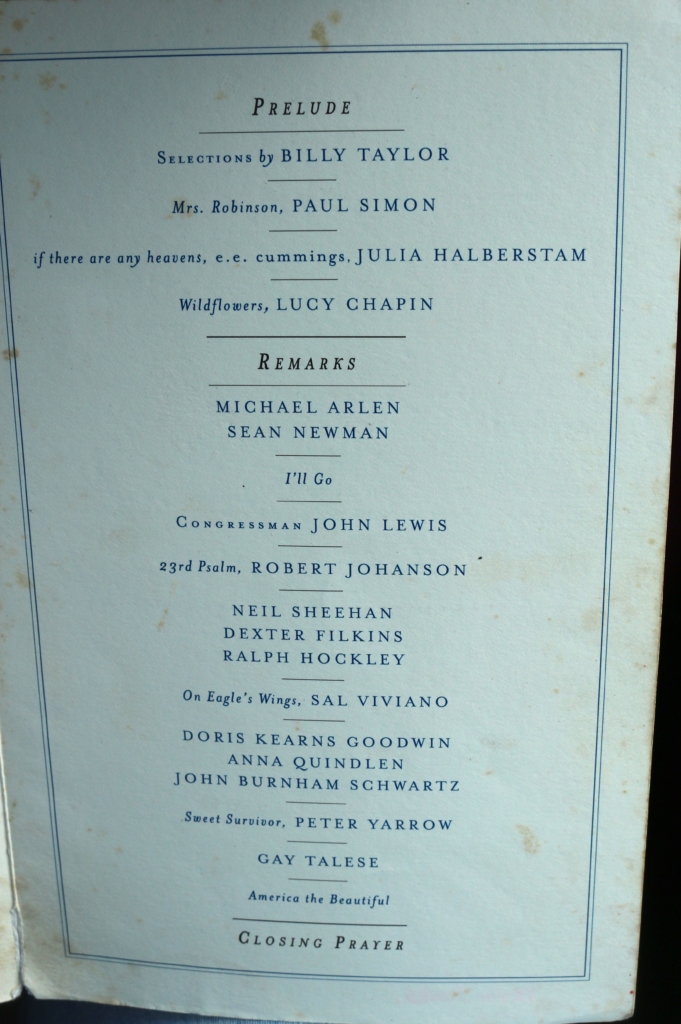

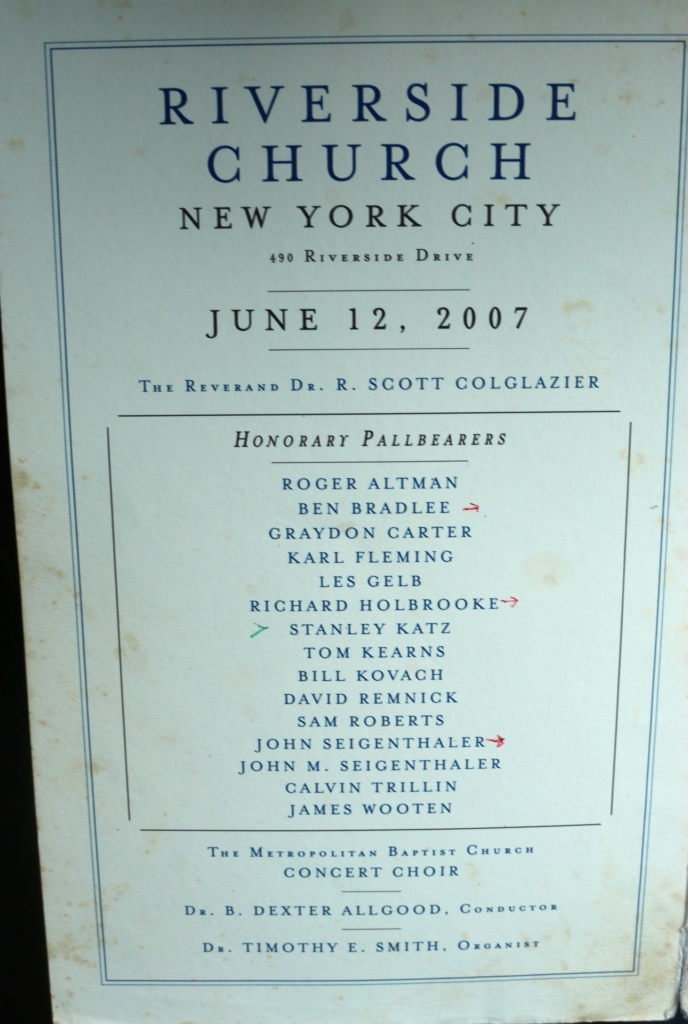

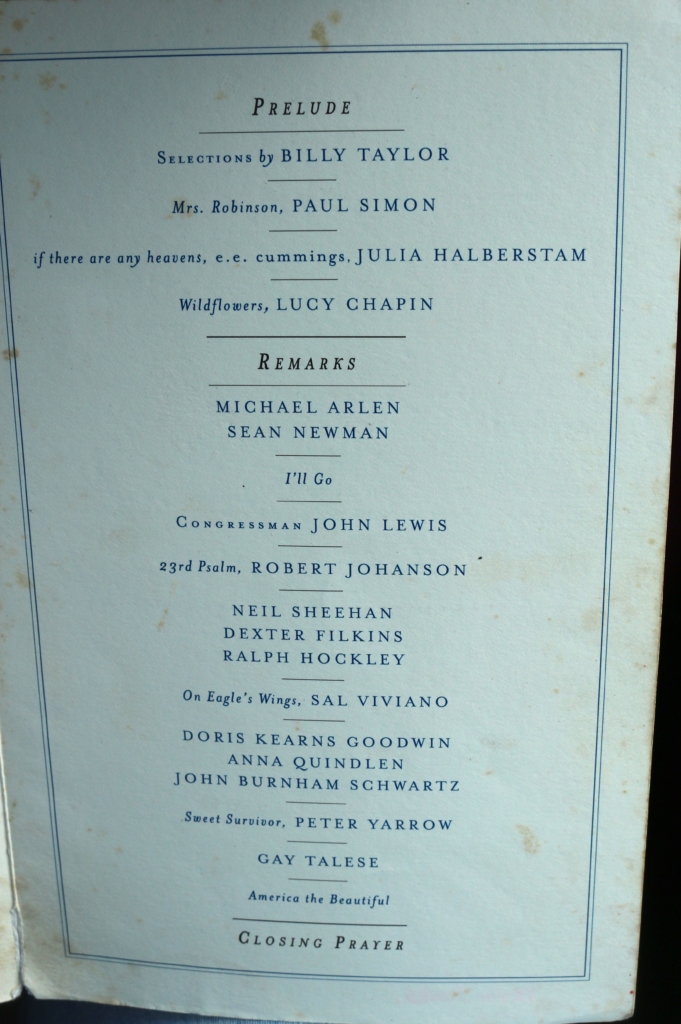

Editor’s note: Cong Tran, or Tran Quoc Cong in Vietnamese naming convention, paid his first visit to the United States in 2007, an invited guest at the memorial service for author and Pulitzer Prize winning Vietnam War correspondent David Halberstam. Mr. Tran had guided and ultimately befriended the journalist during a return visit to Vietnam by the author some years before his death. Mr. Tran was so moved by his invitation to the memorial from Mr. Halberstam’s widow, and so honored to be among the literati in attendance, he saved the printed program (see below). Recently, Mr. Tran shared the messages he sent home from his 2007 visit and gave us permission to share them with our readers, which we are delighted to do. His observations of U.S. culture in contrast to that of Vietnam are insightful and entertaining—at reminder of our national character beyond the context of the Trump regime.

Mr. Tran suspects his first visit to the U.S. was also his last.

Dear Friends,

Good morning, America!

SEAT BELT makes me feel clumsy like spaceman in the spaceship. Trying to remember. It takes some time.

Crossing the streets here is a skill, not an art, like in Viet Nam. Press the button. Magical!

I borrowed a digital camera, but my mind still analog.

In Viet Nam, eat to live. Here, live to eat.

I have a dream. My dream comes true.

Thanks for all your help,

Tran Quoc Cong

Dear America,

Descartes in America: “I DRIVE therefore I am.”

You have driving license, you are somebody. You have wings like angels. I feel disabled because I cannot drive. In Heaven, the angels fly, not walk. My mind, eyes, body in Heaven, but I cannot fly, just borrow the wings.

Mr. Don Giggs offers me a car. Just looking, not driving. How can I change lanes? In Viet Nam, the lanes are built-in and invisible. Very happy to see the sign “Drive Less, Live More.”

House/home is really a castle, fortress. Cars are moving castles, fortresses on freeway.

Best,

Tran Quoc Cong

Dear America,

You are the XXXL country; your meal is, too. A cheeseburger is so BIG, it swallows me, not I it. If I keep on eating like this, I do not think I can walk through the door at the customs counter with the slogan “Keep American’s Door Open and Our Nation Secure” on the day I leave the paradise.

Things are expensive.

In the announcement for the memorial service for Mr. David Halberstam in NYT: “In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations be made to Teach for America in the Mississippi Delta.” Flowers for David, food for me. Teach for America, Teach for my children. Mississippi Delta, Me Kong Delta.

This is an open eyes and mind trip for me.

Thanks for all your help,

Tran Quoc Cong

Dear America,

Memorial Day, Sunday 27 May. Riding bike in Westminster Cemetery, I agree with Thomas Jefferson that “All men are created equal” and buried, cremated equal.

“Flat” means equal in some way, in many ways. In Viet Nam, the graves are not equal at all. In Viet Nam, the hill is for the tombs, death, resting place. Turning your head to the mountain means “pass away.” Flat, low land is for villages, life. In U.S., in reverse.

Now, I know why you are “The Quiet American.” You do not blow the horns when you drive.

I sleep with the sound of click in my dream. “Click It or Ticket.” Seatbelt, please.

See you,

Tran Quoc Cong

Dear America, Good morning, Sun Valley!

Vietnamese local bus from Little Sai Gon to Phoenix, 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Heaven to Hell. Just hot, not humid, like home. No sticky. Anyway, 5-star Hell. Just compare, not complain.

The pages of my high school textbook, Practice Your English, McGraw Hill, appeared along the road. The first time in life I saw desert, cactus, sand, small bushes, hot and dry. Before, I only see dessert, fruits, ice cream, sweets, caramel, after meals. I felt thorny, like cactus when coming to Arizona. Cowboy films 1965 to 67 replayed.

CARPOOL LANE = Mahayana Buddhism. You live, pray, do whatever to become Buddha, and help the others to become Buddha, too. The other lanes on freeway = Theravada Buddhism. One vehicle, one driver.

In the U.S., I live to be delivered. I cannot drive. Thanks for all help. I come to the U.S. with JFK Inaugural Speech, MLKing’s “I Have A Dream,” the image of Apollo 11, and all my high school textbook in mind.

It is my America.

Tran Quoc Cong

Dear Phoenix, Arizona,

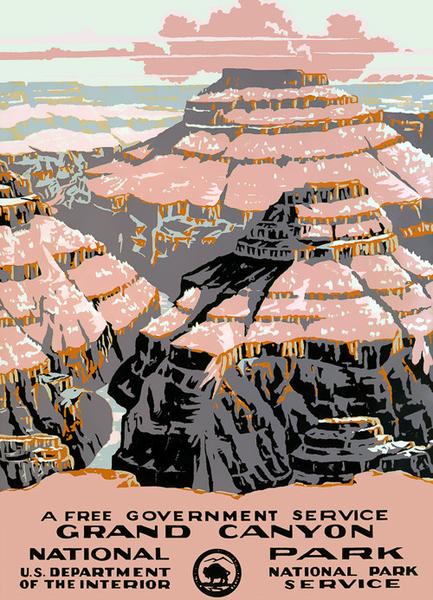

Wooh! Grand Canyon, Great Wonder of Nature, so grand.

“No one should die before they see Angkor,” Somerset Maugham wrote somewhere. To me, “No one should die before they see Grand Canyon.” Coming to Angkor, we stretch our necks UP to see how high. To Grand Canyon, we crane our necks DOWN to see how deep. Angkor, the hand of Man. Grand Canyon, the hand of the Creator.

Riding bike in and around Phoenix in June, I know why the Phoenix puts its head in the ash. To hide from the HEAT.

Buying something, I have to pay tax. I feel itchy. You don’t, do you? Just the system.

See you,

CONG

Dear Old Town Scottsdale, the West’s Most Western Town,

I rode my Iron Horse—bicycle—to the frontier town 113 years after the first settlers came. I met again my boyhood with the cowboy films in my mind, Arizona Colt, Bonanza, The Wild Wild West.

I clicked my camera as fast as the sheriff shot his Colt to stop the bandit coming to town.

I pumped air into my bike tyre in front of the Cavalliere’s Blacksmith Shop, like the cowboys changed horseshoes.

I locked my Iron Horse at the rusty ring once used for horses and mules.

I sent two postcards home from Scottsdale’s first Post Office, where every founding father gathered at mail time, twice a day.

And, I had an ice cream in Sugar Bowl Ice Cream Parlor, to cool down the notorious Arizona dry heat. I am the Man from Nowhere. A really good day.

Bye bye, from Where the Old West Comes Alive,

Tran Quoc Cong

Dear South California and Arizona,

Walking in Mission San Juan Capistrano, I saw Silent Night, so quiet.

Standing in front of Crystal Cathedral, I heard Jingle Bells, so loud.

The bronze sculpture of a woman caught in adultery, “Let the one who is without sin cast the first stone.” They mean tons, tons of glass of the cathedral, neither Magdalene nor adultery.

Thy kingdom comes. Maybe. Looking at all stuff in the U.S. so far, I have felt the Middle Kingdom comes. Everything made in China, except the Cowboys in Rawhide Steakhouse and Saloon.

How come? Hey, folks!

Tran Quoc Cong

Good morning, New York,

You are Grand Canyon turned downside up.

MANHATTAN, I dropped my HAT 3 times while looking at your skyscrapers, you made my neck painful. I became a MAN without HAT or sunTAN, you are my sunblock buildings.

I saw 3D New York vertically, on Top of the Rock and in subway. First time in my life subway, like guerrilla Củ Chi Tunnels. New York, you made my provincial heart choke.

Early morning walk in Central Park, the lung of NY. At home, when getting angry at somebody, we shout madly, “You are a dog!” Watching people dog-walking here, from now on, I will not shout like that. It is so nice. Will find something else, worse.

Oh, my God! I said, Oh, my Dog! I heard the echo from the bench behind. You made me confused.

CONG

Dear 13 Original States,

Promenade in and around Brooklyn (Broken Land), Greenwich, East Hampton, New Canaan. I wonder how many Gods you have. Only one, right? So, why you have so, so many different churches? It doesn’t mean that you are more religious than us. Maybe less. You make God lose his identity. Holding the banknote, I read “In God We Trust.” Singular? Walking around here, I see plurality.

Riding bike around East Hampton and Connecticut is like in the Anderson fairytales. Nice landscape, golden sunshine like honey, green forest, the weather just perfect. I wonder if we need paradise in the next life. God is unfair. Now, I know why you often end your speech, “God bless America.” You bribe Him?

Since coming here, I have had the feeling I am spewed out of the Horn of Plenty together with food. How can I control the temptation?

Forgive me,

CONG

Dear New York,

Welcome to Paradise. We know that even Paradise is not perfect. Spewing out of the subway, woo! Times Square, the Crossroads of the World, not easy to cross due to the crowd. Your five senses are raped by the Most Crowded on Earth, the Call of the Wild.

NEW York is new to me, but OLD to the immigrants in the Lower East Side tenements.

GRAND Central Station engulfs you.

GREAT Depression still in some corners I walked through.

BROADway is really broad.

LONG Island is a long drive, just like your common question in Viet Nam: “How

long to Ha Long?” So long to Ha Long, so long to Long Island.

Burger KING swallows you like King Kong does.

CENTRAL Park right in the center you never miss.

TOP of the ROCK is top of tops.

SUBways like submarines.

WALL Street is only WALLs and GLASS, which makes the TRINITY church so TINY, so PITY.

TIMES SQUARE is not square, but like the hands of octopus.

HOTline 1-888-NYC-SAFE is extremely HOT at Times Square to fight terrorism.

DEAR New York, you are very DEAR, not cheap to live.

Looking at Lady LIBERTY, I think of Lady Buddha. This with FIRE, that with WATER. Two basic things for life. (Lady Buddha with the flask in her hand pouring water down to extinguish the inferno of our life).

New York, you are XXXL. Forgive me, the frog, for the first time, leaving the pond for the ocean. How can I see you all, let alone understand you?

Take care,

CONG

Good Morning, Washington DC,

The bright sunny day: All the monuments, domes, spires, statues rise up to the sky, soar to the heaven, except Viet Nam War Memorial. Black, like the pin, goes deep to the soil. The White House is white. The Black Marble is black.

In the morning, coming to National Cathedral on the hill, I do not see God nor congregation. Emptiness.

In the evening, sitting in the baseball stadium, I see the holy congregation. Their religion is Baseball, singing like church choir. Eating and drinking like sharing the Communion. The 12 Apostles down there bring their spirits up to Heaven with Bats and Balls. When a ball flying to the seats, many people rise up trying to get it like holy blessing. At the back, food and drinks are their “daily bread” they pray for. Some people concentrate on the pamphlet of statistics like Psalms. Baseball caps everywhere like halos. Red and white T-shirts for sale like angel robes. Everyone is happy as they are in Heaven. The first time in my life I watch a baseball game right in the Baseball Cathedral.

I have some books on Baseball Saints by David Halberstam, whose death is the Visa for me to be here. Both Baseball Bible and Baseball Service in Baseball Cathedral are completely dark to me. But I enjoy the Touch of America.

Baseball Bless You, America. Baseball is with you, and you with Baseball.

CONG

Dear Philly, good day Atlantic City.

Woo! The Cathedral of Gambling with the double-ten commandments advised by American Gaming Association. Oh, my God. GAMING looks like GAMBLING. This is that. I wonder if caSINo has SIN within itself. Hope not. But I doubt. And I didn’t see any SAINT here.

Looking at the stream of people coming, focusing their eyes to the slot machines, I heard the words “free to pursuit of happiness” echoing. Losing, return to win back your losses. A win, return to win more. E-Z Pass. Go faster. Go ahead. No clock. Neither day nor night in casino. No-Times Square.

You are in Heaven with thousands of colorful neon lights, make everything DOUBLE, TRIPLE, One four Four. Ecstasy. Drinks are free and welcome to lure you to the dream of winner. Gambling is GAME and BLIND. Knowing when to stop?

Responsible Gaming means Irresponsible Gambling, doesn’t it?

A mime tried to be machine-like. Robot tried to be human-like. Foot Massage and Palm Reading next to each other.

SIN City Mt. Holy Town. The young smile, the old napping.

White, Black, Yellow, Brown skin, the Sun makes all shadows the same on the white sand.

Atlantic City always turned on.

On the drive back to Philly, I saw the sign STAY AWAKE! STAY ALIVE! Otherwise you die. You intend to gamble your life? BOARDWALK is life.

Horn of Plenty.

Food, Fun and Friendliness.

We the People, Pursuit of Happiness.

CONG

Dear Atlantic Ocean,

The first time in life, I dipped my hand into Atlantic Ocean. Just over there is Nantucket, where the ashes of David Halberstam will rest. May my soul hitchhike the ferry across. Should I take some ash and drop it into Me Kong Delta, so he can meet his youth again?

One Very Hot Day. I stopped by the house of Home Sweet Home in East Hampton, and the

birthplace of the author, America the Beautiful in Falmouth.

I walked step-by-step on Boston’s Freedom Trail, not crazy rush like on the Freeway.

In Boston, I slept in the bed of a Marine who was moving from Kuwait to Iraq. I saw all his high school and college pictures, books, souvenirs on the shelves.

In Falmouth, I sent a letter to SPC. Johnson Stephen, who was now somewhere in Iraq, telling him about his beautiful Falmouth village, lighthouse, fishing, swimming and wishing for his safe return, not mentioned the bullshit war at all.

During Viet Nam War, at 15, I found many Xmas cards handmade by primary students in the States, in the Rear, sent to the GIs in the Front. Those were my boyhood toys, which I found in the garbage dump near my school.

Goodbye, Boston. Farewell to the navel of American Revolution. My body is in Jacksonville, Oregon, now, digging gold, but my soul still somewhere in New England with golden memories.

Many American-Vietnamese here never touch the navel of U.S. history and Revolution. They just do nails, run barbershops, and mow the lawns, trying to make $$$. Gold Rush no longer rushes. Hair, nails, and grass keep growing. We cannot stop them. The longer they grow, the more $$$ my friends make. Their American Dream fulfilled. The streets are paved with gold.

Up near Crater Lake , the first time in my life, I touched snow. Two little girls threw snowballs to me. I sat and lay on it. I walked, doubting my feet like Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon.

Goodbye, Boston. 4 July. I left the Cradle of Liberty, Birthplace of American Independence right on her 231st birthday. I ate hot dogs, potatoes salad, baked beans on the East Coast, and watched fireworks in the West, Oregon.

I am in Arcata, CA now.

CONG

Dear friends,

Good evening America. I set foot in LAX at 6:25 PM 21 May. Like Neil Armstrong stepped out of the spaceship walking on the Moon, like the Pilgrim Fathers landed at Plymouth Rock, I stood in line at Visitors Counter, Customs, at Tom Bradley Int’l Terminal in high spirit of Apollo and Mayflower. I giggled like the angels had the new wings ready to fly in Paradise.

My wife feels proud and happy back home in Viet Nam. At long last, at least once in life, her husband goes to America. The Promised Land, Paradise, Heaven, Something Number One.

She boastly told all the villagers, “My husband saw a pumpkin as large as a house in America.” All the villagers listened, mouths and eyes wide open.

Another lady said, “My husband also saw a cooking pot as big as the Village Commune.”

How come! What for?

The answer: “My husband’s pot is used to cook your husband’s pumpkin.”

Best,

Tran Quoc Cong

Dear America,

My soul and mind are untidy like NASA in Florida the day Apollo 11 returned from the Moon.

My visit to the U.S. Paradise is the reincarnation to me. I still have East-West jetlag. Climatically, Paradise. Purgatory, jet lag. It is The 0001 Place (not 1000) to see before you die. 101 Things to Do in life. Not many people have their dreams come true in this lifetime. I am one of the few. Out of more than 3000 photos taken during 90 days in the New World, the Dreamy Land, I had to choose the best, iconic 10. And if only 3 chosen, which ones should I pick out? I told my family, friends, neighbors, colleagues what I have seen:

- the button to cross the streets

- the subway in NY and Washington DC.

- the snow in July at Crater Lake

- the Atlantic Ocean

- the Central Park in NY, desert in Arizona, Redwood Forest …

What I have tasted:

- the biggest burger

- the brownie and trail mix

- the blueberry and yoghurt

- the corn and salmon

What in USA scared me:

- I almost burned my finger with the hot water tap in the kitchen.

- the alarm at my classmate’s house. He gave me his house key, but his wife set the alarm as usual. I opened the door, and the siren barked fiercely. So scared, I just stood at the door holding my passport, just in case the police came. … Goose bumps. “Ask not what American will do for you, but what together we can do.” But, I am alone then.

Yesterday, my daughter asked me if I had any dream, dream to go visit somewhere, somewhere else.

No, I have no dream now. It takes time to have another dream. I feel full, my five senses.

Many thanks, USA,

C O N G