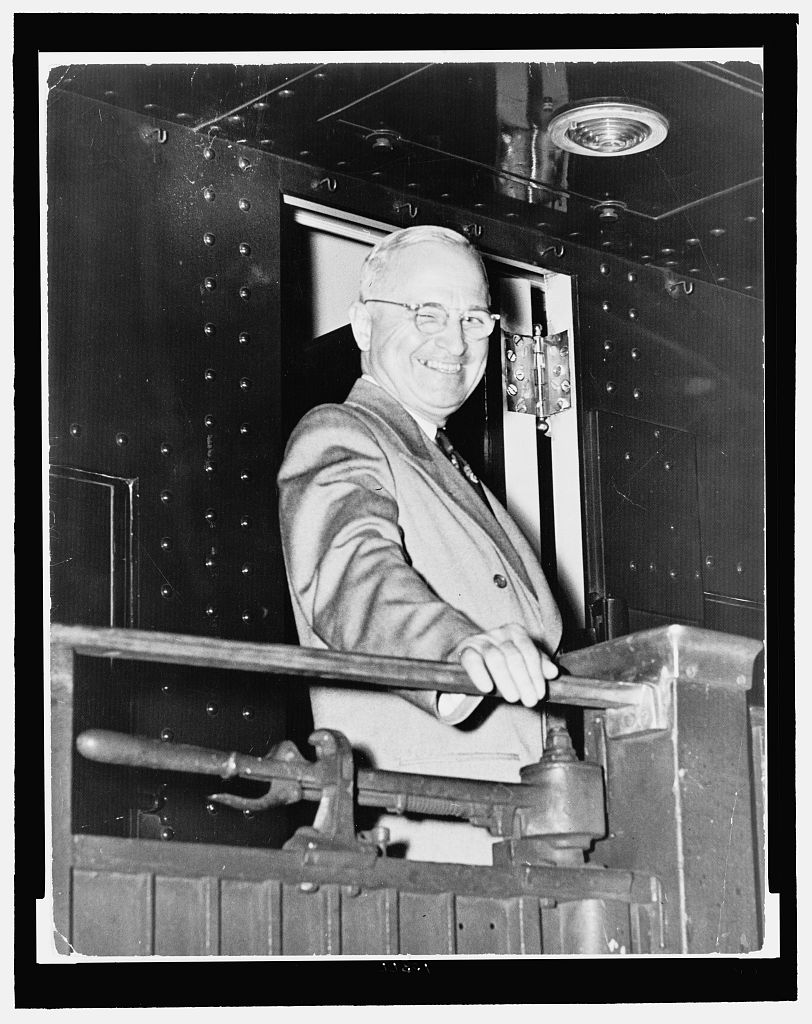

President Truman calls on all liberals and progressives

Address in St. Paul at the Municipal Auditorium.

October 13, 1948, worth revisiting today

Mr. Mayor, and fellow Democrats of Minnesota:

Tonight, I pay tribute to the liberal spirit of the people of Minnesota—in the cities, on the farms, in the forests, and in the iron country of this great State.

In this center of practical liberalism, I am proud to salute a fighting liberal—the next Senator from Minnesota, Mayor Humphrey of Minneapolis. I am also glad to greet the next Governor of Minnesota, Charles Halsted.

Through them, I salute the liberal and progressive forces of this whole region—the forces which are once again on the march against special privilege.

Before I say anything else, I want to take this opportunity to recognize the splendid record which was established by labor and management in Minnesota throughout the war years, and nobody knows any more about that than I do, for I made an investigation of it.

Through those long dark months of war never once was a blast furnace kept a single minute, because of lack of ore. Men who mined the ore and those who manned the trains and the ore boats worked day and night, Sundays and holidays, and there was no work stoppage.

This was also true of the thousands of loyal men and women who labored in your mills and on your farms, and in your foundries and in your forests.

On behalf of the Nation, I congratulate the working people of Minnesota on their splendid wartime performance.

In view of that record, it is all the more strange to me that your senior Senator showed such fanatic zeal in helping to push the shameful Taft-Hartley law through the Congress.

I’m afraid the same thing happened to Joe Ball that happens to most Republicans with a streak of liberalism when they get down to Washington. That’s what I call the “Potomac fever.”

The Republican Party either corrupts its liberals or it expels them. It drove out Theodore Roosevelt in 1912. It drove out fighting Bob LaFollette of Wisconsin in 1924.

It was the Democratic Party of Franklin Roosevelt, not the Republican Party, that held out the hand of welcome to Floyd B. Olson, and to that hero of progressive idealism–George Norris of Nebraska.

And those liberals who have not been driven out of the Republican Party have been changed, like Joe Ball, from fighters on the people’s side to champions of reaction.

True liberalism is more than a matter of words. It demands more than sound effects. It cannot hide behind the catch phrases of the Republican candidate for President-catch phrases like “unity” and “efficiency.” Unity for what cause? Efficiency for what Purpose, I wonder ?

The American people, in this critical year, are entitled to a full and open discussion of the issues. They are not getting it from the Republican candidate for President.

Unity on great issues comes only when the voice of the people has been heard so clearly, so strongly, so unmistakably, the no one … can doubt what the people mean.

It is no service to the country to refuse, in the name of unity, to discuss the issues. It is no service to democracy to conceal the difference between the major parties.

Unity in a democracy cannot be produced by mealymouthed political speeches.

Unity on great issues comes only when the voice of the people has been heard so clearly, so strongly, so unmistakably, that no one—not even the second guessers—can doubt what the people mean.

Thomas Jefferson did not seek unity by concealing the real issues between himself and Alexander Hamilton. He made the issues clear, so that the people could reach a decision. And their decision determined that democracy rather than autocracy should prevail in this great country of ours.

Andrew Jackson did not seek unity with the moneymakers in Philadelphia. He made the issues so clear that the people decided to place the control of the money in the Government of the United States, and not in a few private banks.

Abraham Lincoln did not seek unity with Stephen A. Douglas. He made it clear that this Nation could not continue to exist half slave and half free.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1933, did not seek unity with the economic royalists. He proposed the New Deal.

And today, I do not seek unity by concealing the issues between me and the special privilege groups that control the Republican Party.

I never will seek that sort of unity.

Real unity is behind basic principles and concrete programs. Real unity cannot be achieved without a definition of the issues, and a decision by the American people.

Our foreign policy is an example of this.

I had hoped that foreign policy would not become an issue in this campaign. To that end, I have refrained from taking partisan credit in campaign speeches for the policies which were organized by a Democratic administration, and which others are now claiming credit for so loudly today.

But I serve notice here and now that I shall feel at liberty to correct distortions and keep the record straight.

And when I do that, I shall be glad to give full credit for the significant contributions which have been made by some farsighted Republicans.

We have a large measure of unity in foreign policy now. But it was not always that way. We achieved this degree of unity, only after world-shaking events had made it clear that the vast majority of the people of the United States would no longer tolerate isolationism.

Now, we had no unity in foreign policy in the first national election after World War I. The Democratic candidate for President in that year stood clearly for the League of Nations, and for Woodrow Wilson’s idea of international cooperation.

But the Republican candidate, although he misled the people into believing that he stood for unity, was actually opposed to the League of Nations.

So, when the election was over, the people found themselves with a Republican administration and a Republican Congress that were completely unified–but unified in favor of the wrong policies.

And so the world started down the road to World War II.

We did not have unity in foreign policy in 1940. Even then, with half the world in flames, the Republican leaders were mainly isolationists. They were against aid to the democracies, and they called Roosevelt a warmonger.

The man who is now the Republican candidate for President said that the idea of producing 50,000 airplanes a year was fantastic. And we got to ‘produce 100,000. a

Even in 1944, in the midst of a we did not have unity in matters relating to, foreign policy. During the election campaign in that year, the Republican candidate, who is now running once more, charged again and again that it was the administration’s arbitrary desire to keep men in the Army after the war was over. You all remember that.

He had so little foresight about postwar problems that he felt we could completely demobilize our military strength the minute that hostilities ended.

Now, as a matter of hindsight, he says, “me, too” about building up our Armed Forces.

The unity we have achieved in foreign policy required leadership. It was achieved by men—Republicans as well as Democrats—who were willing to fight for principles before these principles became obvious to everyone.

It was not achieved by the people who copied the answers down neatly after the teacher had written them on the blackboard.

Here again, as in so many other cases, the American people should consider the risk of entrusting their destiny to recent converts who now come along and say, “Me, too, but I can do it better.”

In the meantime, there are other issues in this campaign—big issues. All those issues cannot be hidden or brushed away by pretending they don’t exist.

The issue in this election is not unity. It is not efficiency.

Efficiency alone is not enough in government. Maybe the Wall Street Republicans are efficient. We remember that there never was such a gang of efficiency engineers in Washington, as there was under Herbert Hoover. We remember Mr. Hoover himself was a great efficiency expert.

We remember how he selected one of the richest men in America to be his Secretary of the Treasury. But efficiency wasn’t enough 20 years ago, and efficiency isn’t enough today.

There must be life and hope in government. We must achieve and pioneer in the great frontier of human rights and social justice.

Hitler learned that efficiency without justice is a vain thing.

Democracy does not work that way. Democracy is a matter of faith—a faith in the soul of man—a faith in human rights. That is the kind of faith that moves mountains—that’s the kind of faith that hurled the Iron Range at the Axis and shook the world at Hiroshima.

Faith is much more than efficiency. Faith gives value to all things. Without faith, the people perish.

Today the forces of liberalism face a crisis. The people of the United States must make a choice between two ways of living—a decision, which will affect us the rest of our lives and our children and our grandchildren after us:. … The Wall Street way of life and politics. Trust the leader! Let big business take care of prices and profits! Measure all things by money! That is the philosophy of the masters of the Republican Party. [Or] the Democratic way, the way of the Democratic Party. Of course, the Democratic Party is not perfect. Nobody ever said it was. But the Democratic Party believes in the people. It believes in freedom and progress, and it is fighting for its beliefs right now.

Today the forces of liberalism face a crisis. The people of the United States must make a choice between two ways of living—a decision, which will affect us the rest of our lives and our children and our grandchildren after us.

On the other side, there is the Wall Street way of life and politics. Trust the leader! Let big business take care of prices and profits! Measure all things by money! That is the philosophy of the masters of the Republican Party.

Well, I have been studying the Republican Party for over 12 years at close hand in the Capital of the United States. And by this time, I have discovered where the Republicans stand on most of the major issues.

Since they won’t tell you themselves, I am going to tell you.

They approve of the American farmer—but they are willing to help him go broke.

They stand four-square for the American home—but not for housing.

They are strong for labor—but they are stronger for restricting labor’s rights.

They favor a minimum wage—the smaller the minimum the better.

They endorse educational opportunity for all—but they won’t spend money for teachers or for schools.

They think modern medical care and hospitals are fine—for people who can afford them.

They approve of social security benefits—so much so that they took them away from almost a million people.

They believe in international trade—so much so that they crippled our reciprocal trade program, and killed our International Wheat Agreement.

They favor the admission of displaced persons—but only within shameful racial and religious limitations.

They consider electric power a great blessing—but only when the private power companies get their rake-off.

They say TVA [Tennessee Valley Authority] is wonderful—but we ought never to try it again.

They condemn “cruelly high prices”—but fight to the death every effort to bring them down.

They think the American standard of living is a fine thing—so long as it doesn’t spread to all the people.

And they admire the Government of the United States so much that they would like to buy it.

Now, my friends, that is the Wall Street Republican way of life. But there is another way—there is another way—the Democratic way, the way of the Democratic Party.

Of course, the Democratic Party is not perfect. Nobody ever said it was. But the Democratic Party believes in the people. It believes in freedom and progress, and it is fighting for its beliefs right now.

In the Democratic Party, you won’t find the kind of unity where everybody thinks what the boss tells him to think, and nothing else.

But you will find an overriding purpose to work for the good of mankind. And you will find a program—a concrete, realistic, and practical program that is worth believing in and fighting for.

Now, I call on all liberals and progressives to stand up and be counted for democracy in this great battle. I call on the old Farmer-Labor Party, the old Wisconsin Progressives, the Non-Partisan Leaguers, and the New Dealers to stand up and be counted in this fight.

This is one fight you must get in, and get in with every ounce of strength you have. After November 2d, it will be too late. It will do no good to change your mind on November 3d. The decision is right here and flow.

Against us we have the best propaganda campaign that money can buy.

But we are bound to win—and we are going to win, because we are right! I am here to tell you that in this fight, the people are with us.

With a Democratic President and a Democratic Congress, you will have the right kind of unity in this country.

We will be unified once more on the great program of social advance, which the Democratic Party pioneered in 1933.

We will be unified in support of farm cooperatives, rural electrification, and soil conservation.

We will be unified behind a housing program.

We will be unified on the question of the rights of labor and collective bargaining.

We will be unified for the expansion of social security, the improvement of our educational system, and the expansion of medical aid.

Moreover, we will be unified in our efforts to preserve our prosperity and to spread its benefits equally to all groups in the Nation.

Now, my friends, with such unity as this, we can secure the blessings of freedom for ourselves and our children.

With such unity as this, we can fulfill our God-given responsibility in leading the world to a lasting peace.

Note: The President spoke at 9:33 p.m. at the Municipal Auditorium in St. Paul. His opening words “Mr. Mayor” referred to Edward K. Delaney, Mayor of St. Paul. Later he referred to Mayor Hubert H. Humphrey of Minneapolis, Democratic candidate for Senator, Democratic candidate for Governor Charles L. Halstead, Senator Joseph H. Ball, and former Governor Floyd B. Olson, all of Minnesota; former Senator Robert M. LaFollette of Wisconsin; and former Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska.

The address was carried on a nationwide radio broadcast.

Photo credit: U.S. Library of Congress, President Harry S. Truman campaigning in 1948.

Citation: Harry S. Truman: “Address in St. Paul at the Municipal Auditorium.,” October 13, 1948. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=13046.