What You Need to Know

By Kristi Rabe

My 11-year-old son tried to stab me with his fork.

This was 5 seconds after calling me a stupid bitch.

15 seconds after I told him to go to time out.

33 seconds after I found he had played with a lighter and snuck candy from the cupboard.

1 minute after he said, “I love you, Mommy.”

20 minutes after I hugged him while we made lunch together.

An hour after he finished binge watching Pokémon Season: 1 on a lazy President’s Day morning.

A few days after he received no Valentines at school—even though he had spent the evening before making special cards for everyone.

One month after he was last stable and completely lucid.

Six weeks since the onset of the dreaded flu in our home and three weeks of bedrest.

Six months from being released from residential psychiatric care.

One year after the first time he was violent towards others—me.

Eighteen months from the onset of self-harming behaviors.

Two years after diagnosis of rapid cycling bipolar-I, with psychotic effects.

Three years from the onset of hallucinations and voices.

What you really need to know, though, is it happened four days after a man shot 33 children and staff in the halls of a Parkland, Florida, school. And, with almost clockwork precision, the white gunman was outed by news and media as being a lone wolf with mental health issues—not a terrorist or a criminal. Words like deranged and delusional became his signifier, his adjective. Survivors interviewed were not surprised; they talked about his weirdness, temper, obsession with guns, and violence.

I recognized his condition immediately, even before the list of red flags appeared in articles—before the debates on gun laws, mental health, the lack of organized prayer in school, society’s broken family values, bad parenting, and video games.

I am not trying to perpetuate sympathy for this man. His actions are inexcusable. I don’t have sympathy for him. I have empathy for his adoptive mother.

She spent her years not only as his mother, but also as his advocate through special education and problems transitioning to mainstream. She took him to doctors and battled the maze of the mental healthcare system. In the final two years of her life, she made more than two dozen calls to police, dealt with suspension and expulsion and defiance. She had to work at forgiving her child, who was apologetic and remorseful after throwing things across rooms and threatening her—and she was his only advocate until her death, from the flu.

I know exact the vacuum of guilt, fear, pain, and worry where she lived.

It took eight weeks from the onset of severe symptoms for my son to be seen by a doctor. Mild symptoms from prior years were ignored after countless tests showed no physical disease. It took six months of being seen by a doctor and therapist for official psychological testing to be ordered, and another six months before the testing occurred.

Then there are the medications. While many claim the medications the Florida man took are responsible for the carnage, because they’re given freely to stop symptoms instead of helping the root disease, this is not my experience. These medications are highly regulated down to the exact dates I can pick up new prescriptions for my son. Insurance companies also have a say and have rejected prescribed medicines, because they aren’t on their formulary. These medications were prescribed only after every other possible option was explored and years after I first sought medical help.

Medication has never been the focus of his treatment and it is a battle each time his dosages are adjusted, with the withdrawal and lethargy it causes. I would love if this were not my parenting technique, but with the very little we know about how this disease works, the trial and error of powerful narcotics is my only option for keeping my son from hearing and seeing demons, cutting himself, cutting me—stabbing me.

But even in acute care, doctors have tried to stop the medications—despite a cardiologist’s warning that suddenly ceasing the meds could cause cardiac arrest due to my son’s backwards breastbone.

The nurses, like those blaming the dead mother of the gunman and broken families as the cause of America’s shooting epidemic, believed my son’s issues were my fault.

“Stays at our facility are usually a good way to scare children into behaving,” the intake nurse said while I signed his paperwork.

“Well, there’s more to his situation,” I said.

“Do you have limits at home? Kids need stern limits.”

She didn’t hear me. “Like I said, please read the diagnosis paperwork from his psychiatrist.”

She actually laughed. “Oh, we never look at those.”

I persisted. “We came to your facility a year ago and were told you couldn’t help him because you didn’t have the resources. That was before we had a diagnosis. The social worker insisted he come here when we committed him at the ER, even though you previously rejected our application.”

“We know what we’re doing.”

“I am sure you do, but the testing he has been through is extensive. With the possibility of schizophrenia—”

The nurse took a phone call and directed me to sit in the waiting room. Five minutes later, she seemed surprised I was still there.

“Sorry, do you have more questions?”

“Do you think perhaps a transfer to UCLA with their pediatric schizophrenia unit would be better suited for his needs? That’s what the ER doctor thought was best, and the social worker said you could place him correctly after intake.”

“We don’t transfer patients.”

When he was released, I was promised a continued care plan. I didn’t receive anything but a CPS investigation. My son had told the therapist at the acute care facility—who didn’t read the information about his paranoid delusions—that we kicked his butt, literally, when he was in trouble. After hours of interviews, the complaint was dismissed, and I was given a packet of parenting classes and organizations, and a list of domestic violence shelters.

• • •

I don’t want to stigmatize others with mental illness. My son is a rare case, having symptoms of not only schizophrenia and bipolar, but also paranoia, OCD, ODD, ADHD, anxiety, and some autism spectrum disorder symptoms. Most do not deal with more than two or three of these illnesses. I know firsthand that the American mental healthcare system is completely broken in a way most cannot comprehend. Every service, every treatment is a battle with bureaucracy or insurance companies or both. We have been rejected from all but a few care centers out of the hundreds I’ve contacted.

So, why write about my son’s mental illness?

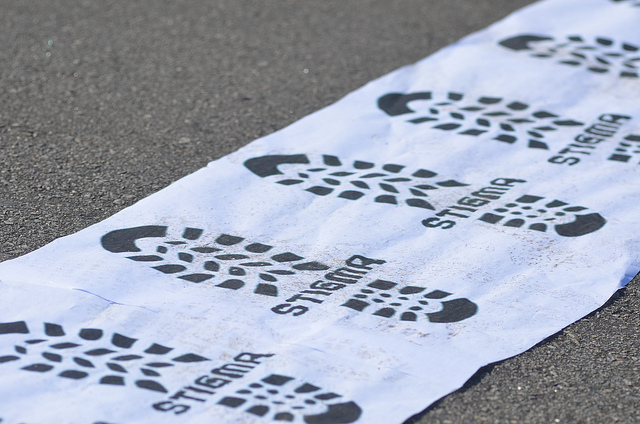

Because correlation does not equal causation, but society’s stigmas are not just a vague PC problem.

Because due to his condition, I censor his entertainment. He doesn’t play violent video games. He doesn’t watch violent movies. He is still obsessed with death and destruction.

Because I cannot teach him religious stories. The rainbow of his logic twists the black and white of religious dogma into paranoid delusions.

Because I have to count the positive comments I make to ensure they outnumber the negative comments. I sometimes must search for nice things to say about my own child.

Because he has to be on a formal system to understand how he is behaving. He has no sense of self-control, no impulse control; he doesn’t understand the concept of following rules.

Because my days are mundane drills of routine to save myself from battles and meltdowns. There are no day trips to a park or museum or carnival.

Because after a meltdown, I hold him in my arms and he cries and begs God to not be this way.

Because he has no friends and is considered odd.

Because his fondest wish is to be a minority so he would finally belong to a group.

Because he is convinced if he were somehow someone else, he would be okay.

Because I only get to see the real him, lucid and stable, every few months for a brief week or two.

Because his mood can shift as quickly as his bright green eyes in a storm.

Because I lock my bedroom door at night—out of fear.

Because I watch with jealousy as friends raise children and celebrate milestones.

Because I have to convince myself each day it is worth it to leave my bed and fight again.

Because I do, most days, for him.

Because I love him.

Because I lose my temper more than I like to admit.

Because I sometimes do not like my child.

Because my guilt is my personal, lonely hell.

Because I don’t want my son’s teacher to have a gun near him.

Because I contemplate his possible crimes in the future more than the possibility of his becoming a victim of violence.

Because, if he cannot control his impulses with a fork, I do not believe he has a right to a gun—no matter what men wrote on a piece of parchment more than 200 years ago.

Because I see my son in descriptions of a gunman who murdered 17 people.

Because I feel utterly alone and weak and frustrated and tired and judged.

Because I know the gunman’s mother felt the same.

Because those who use her life and parenting as an argument for or against gun control need to know how it feels.

Kristi Rabe is a freelance writer and construction project manager in dreary Moreno Valley, California. She is also the adoptive mother of a child with serious mental health issues and special needs. She received an MFA from UCR Palm Desert, Low-Residency Program in 2014. Her work has been published by Bank Heavy Press and Verdad Magazine. Most recently, she was featured on the Manifest Station’s literary website.

Photo credit: North Carolina National Guard via a Creative Commons license.