Beware a Kinder, Gentler American Fascism

By David L. Ulin

Originally published by LitHub, November 16, 2016; used with permission of the author.

Let me begin with an admission: I don’t know how to write about this. I’ve been trying since Wednesday morning, day after the election, when I awakened with what felt like the worst hangover in the universe—and without the benefit of having gotten drunk. I’ve tried writing about Harvey Milk and the effect of the White Night Riots on the movement for gay rights. I’ve tried writing about vote tallies and the Electoral College. Tuesday night, I spent half an hour on the phone talking my son off the ledge—or no, not off the ledge, since it was the same one I was standing on. Later, I walked my daughter home from our polling place, where she had spent the day working and had voted in her first election; as we neared our house, she turned into my shoulder and burst into tears. I don’t want to make this personal, but of course I do. All politics is personal, or grows out of personal concerns. I am the father of a gay man and a straight woman, and both are at risk today. If you don’t think this is personal, then you better get out of my way.

I am not an activist, I am a writer. But we are all—we must be—activists now. As to what this means, I don’t yet know. Yes, to protests; yes, to registering voters and contesting elections; yes, to believing—to continuing to believe and fight for—this fractured democracy. But even more, I want to say, a yes to kindness, a yes to the human values for which we stand. This week, I began to dismiss my classes with a wish or admonition: Be good to each other and be good to yourselves. They’re scared. So am I. It seems the least that we can do.

What astonishes me is that the world continues. What astonishes me is that life goes on. What astonishes me is that I can step outside at break of evening, dusk deepening like a quilt of gauze across the city and everything looking as it always has. Down the street, a neighbor walks her dog while chatting on her cell phone; the smell of wood smoke lingers in the air. Just like last week, just like normal, although what does normal mean anymore? We have an anti-Semite as advisor to the new president, who is promising a first wave of deportations immediately after Inauguration Day. And yet, what frightens me is that in a year, or four months, this election, this administration, will become normalized, as will whatever happens next. We will get on with it, we always get on with it, but I don’t want to get on with anything. The dislocation is maddening: the inability to imagine a return.

I’m writing from a place of privilege; I understand that. I am a straight white male living in a (relatively) progressive state. Still, let’s not be fooled about what this means. Hate speech in a high school classroom in Sacramento, a gay man struck in the face in Santa Monica. Objects in the mirror are always closer than they appear. I have relatives who chose not to vote for president in Pennsylvania. In Pennsylvania, where the final margin was 68,000 votes. If this is a Civil War, it is one in which the battle lines are not the Mason-Dixon line but the driveways that separate us from our neighbors, our place in line at the supermarket, the traffic light at the nearest intersection, the kid at the next desk in our schools.

What do we do about it? We stand up, vocally and without equivocation, for the most targeted and the most vulnerable, we give our money and our comfort and our time. We are still a nation of laws, with a Constitution, and an opposition leadership. This, however, cuts both ways. If fascism or autocracy takes root here—and the seeds have already been planted, let’s not delude ourselves—it will be a kinder, gentler fascism, couched in the rhetoric of the American experiment. Normalized. That’s the America Philip Roth describes in The Plot Against America, in which Charles Lindbergh wins the 1940 presidential election and brings fascism to the United States. Roth’s country is one in which the World Series is still played in October, and kids sit in the kitchen with their mothers, talking about what they did at school. “Do not be taken in by small signs of normality,” Masha Gessen wrote last week on the blog of the New York Review of Books. “…[H]istory has seen many catastrophes, and most of them unfolded over time. That time included periods of relative calm.” All the same, Gessen reminds us we must “[r]emember the future. Nothing lasts forever.” To forget the future is to give up hope, and hope is our most prevailing necessity.

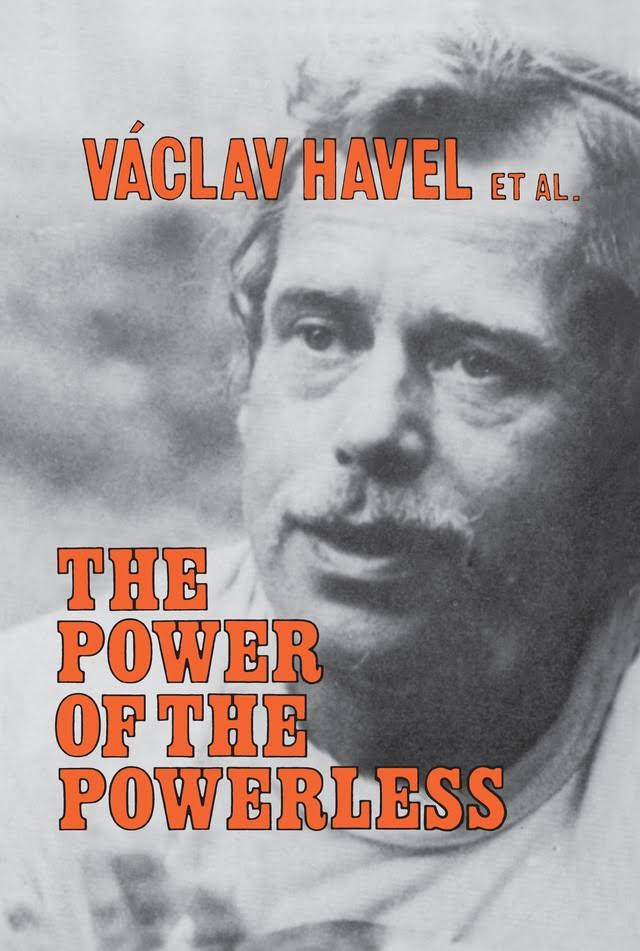

And hope, I want to say, begins with each of us. And hope, I want to say, begins at home. I keep thinking of Vaclav Havel, that dissident turned president, who in his 1978 essay “The Power of the Powerless” stakes out the position of a “second culture,” in which freedom begins as a function of our willingness to behave as if we are free. What makes this essential is its insistence that we are accountable, that the reanimation of “values like trust, openness, responsibility, solidarity, love” falls—personally, individually—to us. Keep the record straight, in other words, bear witness and participate, but also hold onto yourselves. “Individuals,” Havel writes, “can be alienated from themselves only because there is something in them to alienate.” I make a choice, then, not to be alienated; I make a choice to engage. I make a choice to preserve the values of tolerance, of love, of looking out for the other. I make a choice to act as a human being. “If the suppression of the aims of life,” Havel continues, “is a complex process, and if it is based on the multifaceted manipulation of all expressions of life, then, by the same token, every free expression of life indirectly threatens the post-totalitarian system politically, including forms of expression to which, in other social systems, no one would attribute any potential political significance, not to mention explosive power.” This is the resistance I am seeking, this is the revolution we require.

At heart here is a different sort of normalization—the normalization of who we are. We live in a country where we’ve been told (are being told every day) that we don’t belong. What do you think hate speech is? An attack on our right to consider ourselves American. I am an American, however, and so are you … and you and you and you and you. I do not walk away from that. We—and by that, I mean we in the opposition—are a nation in our own right and we have to stick together, to find the necessary common ground. My mother, who turns 80 in a couple of months, told me the day after the election that she had been talking to a younger friend, a woman with a teenage daughter; “I won’t live to see it,” my mother said, “but you and your daughter will.” She was referring to a woman president, but also, in a sense, to the restoration of what let’s call American values, for want of a better phrase. The conversation made me sad, and yet we can’t give in to sadness; that is not our luxury. At the same time, it is also necessary that we express it, that we can tell each other what we are feeling, how we are.

So how are you? I am worried, I am angry, and (yes) I am sad. I am also trying to live my life. This is the normalization I will not yield. Call it second culture. Call it whatever you like. I am reeling, we are all reeling, but I am teaching, I am writing, I am trying to take care of those I love. Saturday evening, I went out for dinner with my family. We sat across from one another and tried to be in each other’s company, which remains, as it has ever been, its own small sort of grace. The following morning, my wife and daughter began making plans to go to the Women’s March on Washington. This is where we are now. This is who we are. Resist. Remember. Stick together. Be good to each other and be good to yourselves.

………………………………………………….

David L. Ulin is a contributing editor to Literary Hub. A 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, he is the author, most recently, of Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles, a finalist for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay.

Reading recommendation: The Power of the Powerless by Václav Havel.