Lithium & High Heels

By Heather Dorn

Barbie’s feet come preformed for sexiness, but the rest of us must learn to curve our arches like a playground slide. We start young, even as babies, barely able to walk, staggering up church or pageant stage steps—sparkling quarter inch heels, lace dresses, makeup bruising our eyelids blue, punching our cheeks red. This for a trophy, some money, salvation, attention.

When I’m out with women friends, sometimes men will ask to buy me drinks. I usually say no because there is an implication that if I accept a drink, I owe him attention.

Even when I say no, they often still bother me: You should sell thrift store watches to Boscov’s, one man tried to convince me after I told him I was getting my Ph.D. Sometimes I say I’m married, or have a boyfriend, or have a girlfriend. Sometimes I let someone else’s ownership of me be a reason so a man will listen to my no, when I’m tired and my no is not standing on its own. Of course, I don’t always say no.

Once a friend asked how I got some pot lollipops I’d brought to a party. Someone gave them to me, I said.

But who? she repeated. How much did they cost?

I don’t know. Someone said, ‘Do you want these’ and I said ‘Yes’ and I took them.

I hate you, she pretended to hit me.

Beauty is subjective, except my mom says it isn’t and I can see her point. I don’t have any physical reaction to that music, that poem, that mountain, that man, that woman, but I know she is considered “beautiful.” That eye matches that other eye and this is beauty. I learned it from TV and magazines and movies and pageants, and the way my mother tilted her head in the mirror and knew her light. Sometimes an imperfection is called beautiful, when it accompanies matching eyes.

Beauty is subjective, except it isn’t—like sanity. Is sanity subjective? Is sleeping in a closed, dark closet as a teen a quirk or a sign of manic depression? If you ask my mother, it’s not normal. Is vacuuming at 3 a.m. insane? My mother says that’s normal. And my mother knows what is correct, true, normal, attractive. She tells me how to be these things. She once told me I had my Aunt Julia’s nose, thin and narrow, and she would help me get a nose job to fix it when I got old enough. To this day, I dislike my nose. I could not fix it now though because I have finally learned what I really look like and so it’s too late.

It’s hard for me to be attracted to someone who I don’t know. This chasm between my feelings of attraction and the objective standards I know I’m supposed to use to gauge attractiveness leave me feeling an outsider in conversations about beauty. When other girls were falling in love with boy bands and actors on the covers of magazines, I was pining after characters from Victorian novels or 80s teen movies. I didn’t want to kiss Molly Ringwald, I wanted to kiss Claire from The Breakfast Club. I didn’t feel like Ally Sheedy, but Allison Reynolds, right down to the makeover at the end. I didn’t want to date Judd Nelson, but John Bender, and I wanted to be and kiss Claire, and to wear one or both diamond earrings she so easily gave away to her one-day make out partner.

Girls like Claire always had the right everything. It’s not just clothes, or hair, or makeup, or nails, or shoes, or bras, or jewelry, or purses. It’s also the time and space and money to keep, use, and update these items. Makeup runs out, hair straighteners break, clothes go out of style.

When I first started making semi-regular money babysitting, I spent it on drug store makeup and the shampoo I wanted. Coconut smell. Back then I was still getting hand-me-down clothes, and curlers, and shoes. Now, almost all my shoes are new.

My ex-husband never minded me spending money on my hair, as long as I kept it long, but requested that I cut his hair so that he didn’t have to pay to get it done. More than saving money, I think he was trying to avoid people. He hated people. The small talk was probably annoying to him as well. Though he’s much better at small talk than I am.

Small talk is filling the air with noise when silence will do. He can talk to people for an hour about the weird Binghamton weather, get to know them slowly over a few years, and then still not really know them when they later move away. People will think he is a really nice guy and so cool for helping them move. They don’t know he helped them move to get them out of his life.

I will not help anyone move. It’s tedious and I’m weak and tired. I will not talk for an hour about the weather. I don’t check the weather or carry an umbrella. That’s so much planning, just to avoid water. And who remembers rain exists when the sun is out? Instead, I will run up to a new person, shake their hand, and launch a manic stream of words: My name is Heather! I’m bipolar and like Indian food! Years ago I was triggered by some PTSD and went through extensive therapy! I’m not close to my family! I’m so glad we will be teaching this course together this semester!

I want to know people all at once.

Or more correctly, I want them to know me all at once. It takes time to get to know someone—and I’ve got no time for that. But part of my bipolar brain can be not caring or caring so much that it stops me from interacting at all for fear of fucking up. Like saying fuck at the wrong time.

I was worried I was going to say fuck when I went to my ex-husband’s first work dinner. Most of the people he worked with, including his boss, are nice, respectable, Christian people. I doubted that they cared for all my facial piercings: an eyebrow ring, tongue ring, lip ring, and nose ring at the time. I was sure that I was going to fuck up, irrationally nervous that when we prayed before the meal I’d be called on to contribute: Hey Jesus, thanks for this high-fucking-class food, thanks for fucking dying for me and shit, p.s. I don’t think your mom was a virgin, A-fucking-men.

This would not work.

I was out of practice with my high heels too. The day before the dinner, I spent hours in the shoe section of Macy’s trying on heels. I was teaching at the university, going to school full time, and had toddlers at home. I didn’t feel at all connected to the person who had once worn heels. Her body was gone and wearing heels was different now. Three pregnancies had made my foot grow a half size. Size 9 heels looked huge when the clerk put the box next to me, a green pair nestled in the paper.

I put them on and stood up, balancing on the thin pegs.

They’re not even that tall, the saleswoman anticipated my complaint.

I don’t think I can walk in them, I staggered around the department like a newborn puppy.

You’re not going to find any shorter. It had been hours and she was done with me.

I was done with me too. I knew the dress needed heels. It was that kind of dress, the shoe lady told me, the dress lady told me, magazines told me, TV told me, movies told me, my mother told me. I knew I had to wear high heels with that dress and that dress to this event. I knew I had to go to this event and to not say fuck. I knew this is what was expected. It’s sometimes hard to tell whether to do an expected thing or whether to jump out the window, my brain always teetering on the window sill.

My ex didn’t go to my work events in uncomfortable clothes and painful shoes, but I’ve never driven him to the hospital when he wouldn’t stop throwing a training wheel down the driveway or listened to him worry for hours about a sent email.

Relationships are not equal. This is mathematically impossible.

Once, shortly after moving to Binghamton, he and I were walking through the mall with our kids and his parents in tow. His mother was getting on my nerves. She had a way of slapping me in the face and making it look like a caress. I was arguing with him, instead of his mother, because arguing with her wasn’t an option. Because he never stuck up for me. His parents were not the type of people to show emotion, especially not in public. The only acceptable emotion was laughter, and even then, let’s not be rude about it. I was growing angrier and louder as we argued, until he finally asked me to quiet down.

That was when I turned around, in the middle of the mall, my children and in-laws standing behind, and yelled, “Fuck off!”

Later, recalling the Fuck off incident, we would laugh. This was once I had been on a Depakote, Seroquel, Lithium cocktail for a few years and he probably didn’t feel the weight of my altered states any longer. Sanity is subjective—except it isn’t.

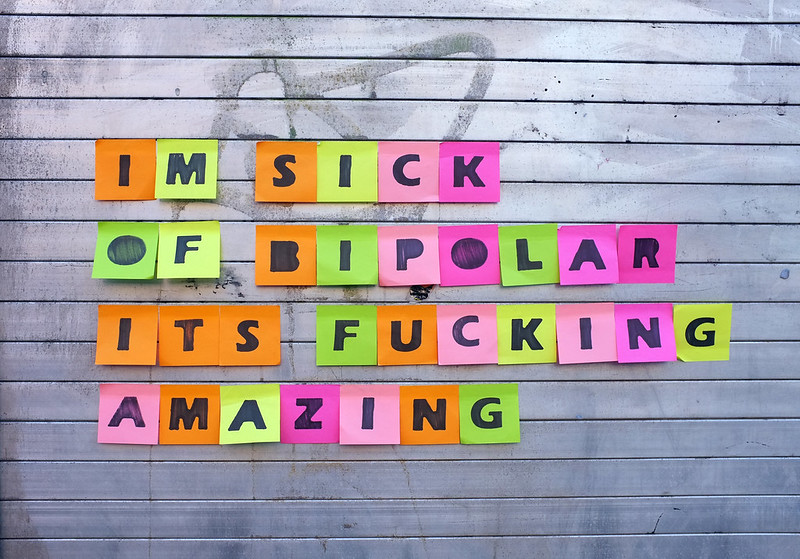

But not every part of mania is bad. Some people say they wouldn’t be bipolar, if they could choose, but it affects everyone differently and some days I feel I won the neurological lottery.

I remember the times when I had sex with my ex before he went to work, called him home for sex at lunch, and then begged for sex when he walked through the door that night. I remember wearing high heels all day, catching a glimpse of my legs in the full-length mirror, my brain buzzing at the sleek shimmer of glitter lotion that made me feel like magic. It was hard to think of anything other than sex and it was never enough. But this would only last a couple of weeks.

Usually followed by a crash.

And the crashes were low. Weeks in bed. Extreme physical pain, just from being. Crying daily, all day. It’s impossible for me to remember the way it felt because I can only feel that distorted when my perception is altered. I do remember many moments when I thought everyone I knew would be better off without me around.

I also thought about driving off an overpass.

And mania could be a problem too: feeling like a god was countered with the paranoia that everyone I knew was talking about me behind my back, hated me, that my husband of over twenty years was conspiring to leave me to be with an unattractive woman with uneven eyes and a perfect nose.

Hypomania is less intense. When I was hypomanic in my Masters program, I planned my semester in a weekend. Class plans for fifteen weeks in three days. When hypomanic, I paint, I write, I even clean. I don’t need to sleep. I love the way I feel—like being high but better because I’m high on me and I’m all throughout my veins.

The medication takes this away from me.

And the depression and the mania, it takes all these away from me. It makes me more level. More like myself or less like myself, whichever way you see it.

I also take pills for attention tremors, which are caused by the Lithium. The tremors occur anytime I’m trying not to shake, which makes putting on nail polish much harder than in the past.

I try to put on new nail polish once a week, but it has been every two to three weeks lately. When I’m putting on nail polish I can’t really do anything but put on nail polish. I can watch TV, or listen to music, or have a conversation, but that’s all I can do. And sometimes I do none of this. I do my nails in silence, in nothingness.

I’m trapped in a space of open blankness and I can’t leave until the paint dries.

Some people like my nails and tell me. My lovers. A colleague. A student. I’m glad they like my nails, even though I did my nails for the reflection time, for the moments I look down typing and think they look like candy, for licking them when I’m alone, for the pictures I get of them shining on a coffee mug that make me feel like I’m a hand model, for some feeling of accomplishment, for some discovery of art.

It’s been a few years since I started my current cocktail of medication, and I sometimes wonder if I take it to make myself more comfortable or to make everyone around me more comfortable. Of course, it does both, but I wonder what my goal is. Most days, I think I take it for me, so I can wake up in the morning and get to work, so I can go the day without telling a friend to fuck off, so I can think about something other than sex.

But some days I think I take it for everyone else. The world is set up for people who don’t need to take pills.

I wonder if I could ever be cured, though no one ever has been. I decide it’s not a disorder, being bipolar. Maybe it’s okay to feel like a god. Maybe it’s okay to see colors like flavors. Maybe it’s alright to stay up all night until I fall over asleep from exhaustion, a pen still in my fingers. I don’t want to take my medication. But I must work tomorrow, so I swallow my pills.

I’m always glad I did in the morning. I argue with myself every night.

Heather Dorn was born with a plastic spork in her mouth. As a child her mother took her to Taco Bell so she’s Taco Bell obsessed. She grew up mostly in California and Texas, knowing Taco Bell is not Mexican food, but nostalgia is yummy. Heather’s poetry, fiction, essays, and art can be found in journals like The American Poetry Review, Paterson Literary Review, Ragazine, and The Kentucky Review. She earned her Ph.D. from SUNY Binghamton, where she is a lecturer. After work she goes home to watch true crime. On the weekends, she wishes she had a washing machine.

Photo credit: jon jordan via a Creative Commons license.

A note from Writers Resist

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.