Man with a Knife

By Tara Stillions Whitehead

ENTER death as sound blackening an already shadowy scene—as a long, hard lament from the HORN of the failed getaway car. Then, as a YOUNG WOMAN. Everything is lost; everyone has lost. At this distance, death is an exquisite execution of convention. A triumph of method acting. Near-perfect cinema. It will be studied and taught and adapted and celebrated for its shape.

It is easy to rage over a newly motherless child.

*

It happened in broad daylight. It happened at night. It unmistakably happened. It was day. It was night. It was. (It still is.) He bent him over, he broke him in half, he bent him until he broke and couldn’t be put back together again. He told him this is a common occurrence. He used the word occurrence by mistake. This is how guys let off steam, he said. This is how you make friends in the business, he said. And this is how you get away with it. Over here, behind the condor, between the generator and the empty two-banger. It’s fast, he said. It’s hard. It hurts, he said. But that’s okay. That’s part of it, he said. That’s part of what makes it great. When you’re older, you’ll appreciate it, he said. The pain. You’ll see I’m right, he said, in a voice that was sure, in a body anticipating relief. And then he folded the boy hard into that posture that broke him. He demonstrated, the boy said in a documentary twenty years later, how to ruin a life.

*

ENTER deception as a WOMAN whom we have never seen but whose rumored infidelities keep the emotional plot moving, whose fatal intrigue is meant to distract the players from burgeoning political avarice. While the newspapers pay for pictures, big money for images of fucking or almost fucking someone else’s husband, someone desiccates the orange groves to the north, slakes penniless farmers with broken promises, and forges the names of the dead. The inland empire is ripe for annexing, the groomed child is ripe for killing.

ENTER a millionaire to execute both. It’s savage. It’s noir. It’s a captivating example of how to unravel humanity on a screen.

It’s easy to rage over pictures that hide the truth.

*

I’ve told the bloggers, she says. I’ve told the LA Times, she says. Didn’t you see my interview on The Talk? Read my sworn affidavit, she says. Read all three of them. Forget the Deadline Hollywood nonsense. It’s a hashtag epidemic. It’s total bologna. I know my husband. I know everything about him, more than his doctors. He sleeps in the fetal position—when he sleeps—and he only fucks women, okay? Vaginas. Tits. Never anal. Not even plugs. A wife knows, okay. Ask me anything. That beauty mark that made him a millionaire is a chicken pox scar. He didn’t grow up in Reseda. He’s from rural Pennsylvania. His mother was Mennonite and he didn’t learn to drive until he was twenty-fucking-three years old. His father died of sepsis after he severed his hand in a grain mill, and his sister Lucy committed suicide at ten. Ten. If that doesn’t fuck you—Look, E. worked his ass off to float to the top of this cesspool. He didn’t fuck that casting director’s kid in the back of his town car. He didn’t sodomize any child stars. It’s a hashtag epidemic. It’s social media. It’s a lot of angry women and crying faggots, okay? This isn’t just business these people are fucking with. It’s the whole entertainment industry. Thousands of people. It’s livelihood—yours, E.’s, and mine. Everyone’s. My husband doesn’t fuck kids, okay. A wife knows. Now put this bitch to bed so we can get back to production.

*

ENTER truth as obscenity, as a confession: She’s my sister. She’s my daughter. She’s my sister. She’s my daughter. She’s my sister and she’s my daughter. It is cunning and unexpected. It is one of the most spectacular scenes in all of film. Any film professor with a degree in cinema will assure us of it. The brutality, they say—

It is easy to rage over a fatherless daughter.

*

That’s great. You did great. Do you high five? Alright, high five! Okay, okay. So, next time we meet, it’ll be at my other office. Seventh floor of the Burbank building. The third office to the left. Be sure to wash up first, okay? You can’t be sticky during an audition. There’s a bathroom in the foyer off the elevator. It has good lighting. Take your time. Practice your lines for the new scene. Do whatever you gotta do to get warmed up, okay? Be sure to tell your mother to wait downstairs again. She’ll only distract you. Mothers are just distractions. Tell her to get a coffee and take a long walk through the studio store. Tell her she can buy anything she wants. You like Harry Potter? Avengers? The Flash? Of course you do. Tell her to give the cashier my name. It’s on me. Everything is on me. Isn’t that cool? It’s pretty cool, right? That’s what it’s like to be famous. You can buy anything you want. You can go anywhere you want. Do anything you want. It’s pretty cool. Hey, come here. A little closer. Yeah, right there. Perfect. Are you scared? Don’t be scared. It’s okay. I know what I’m doing. Trust me, okay? Can you trust me? Think about your mom and all the things you’ll be able to buy her. Think about how cool your house will be once you make it big. Don’t worry. I know what I’m doing, okay. There. See. That’s not so bad, right? It’s kind of good, isn’t it? Right. Right. Now, tell me … how would you like to be famous?

*

Top 10 Anticipated Series in Development: [3/27/2020]

.

.

.

4. Untitled #metoo Project | NC-17 | Action – Drama – Suspense | Announced

Attorney who “would never put herself in a position to be raped” represents network mogul slammed with allegations that he sexually assaulted children and young actresses.

8-episode mini-series| Director: M. Garcea | Starring: C. Beavers, M. Roberts

*

One of the broken boys died of addiction. But not really. He died of pneumonia. But not really. Can shame kill? Because the boy’s blood was infected with it. And whether it was the shame that caused the emptiness that caused the use that caused the addiction that caused the pneumonia that caused his death—he can never confirm. Dead boys can’t defend themselves or explain. They can’t talk at all, not like living boys, the unbroken ones anyway.

It is easy to rage over a boy who cannot speak.

*

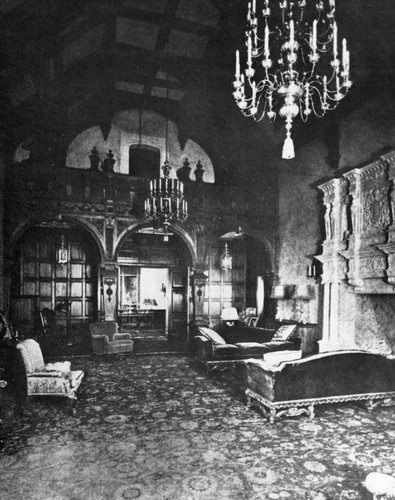

85 EXT. – STONE CANYON RESERVOIR – DAY – MAGIC HOUR (Omitted) 85*

LOW ANGLE BEHIND the feet of two men standing on the gravel perimeter of the empty reservoir. DARK RINGS mark varying latitudes of higher water levels, times long gone. One of the men, M., 37, wears khaki shorts and a bulletproof vest over his button-down. The dark-suited man to M.’s right, K., 55, speaks in sharp monotone throughout, hands resigned to his pockets. As the SUN SETS, we STAY ON the men’s backs, sometimes catch a glimpse of them in profile.

M.

You’ve seen Chinatown, right?

K. nods.

M. (CONT’D)

The scene where Gittes gets his nose sliced. That

was shot right over there.

M. points off-screen.

M. (CONT’D)

Polanski played the attacker.

(pause)

He had a choice, you know. As the director. He

chose to be Man with a Knife. No name, just a man

and his weapon. He chose to play that role, to be the

one to say “kitty cat” instead of pussy. To be the

guy who disfigures Nicholson and tells him to stop

trying to uncover the truth. It was 1973. Polanski

had a thing for knives.

(turns to K.)

I’m not killing myself.

K.

No one really wants that.

M.

A lot of people sure sound like they do. Trolls, E.,

the media, lawyers—

(looks at K.)

Well, most of them.

K.

Hey, I’m here for you, buddy.

M.

These Twitter trolls. They’re stuck in a time warp.

I’m forty-two. I’m married and have two daughters.

But people see my name in their feeds and they

think time hasn’t passed. They think I’m still that

goofy kid they loved almost thirty years ago. How

could anything bad have ever happened to him, they

ask? He was so goofy and healthy, he never looked

hurt. But now they hate me. For nothing. For

nothing except telling the truth. People hate when

the truth gets in the way of what they believe, so if I

just disappear, if I’m not here to force them to

choose truth—

(stops himself)

Fuck.

The SUN lowers into frame, FLARES. The men become SILHOUETTES.

M. (CONT’D)

You know, Polanski experienced total brutality in

his life. He fled the Nazis. His mother died in

Auschwitz. He lost Sharon in the most horrific way.

His life is the culmination of catastrophic

circumstances. It’d be easy to forgive a person like

that, to say they were so fucked up as a kid, as a

young father-to-be, that they didn’t know how to do

things right.

(pauses)

Except that when you’ve been the victim, you know

what wrong is, and you know complicity. You

choose to do bad. Polanski had a choice. Those

kids—Sam Gailey, the girls in Gstaad—

(pauses)

They’ve heard it too. “You’re lying.” “Go kill

yourself.” “Give us back our brilliant Polanski.”

(pauses)

I’m not killing myself.

K.

You have a lot to live for, pal.

M.

People marvel at how Chinatown ends, how fucked

up it is. But they like it. They like that Gittes is too

powerless to save anyone. It makes their own

powerlessness okay. People thought it was real hard

to end a film that way given the circumstances of

Watergate, the paranoia and desire for transparency.

But then they saw their own powerlessness. And

they thought, well shit, here’s a movie that tells it

like it is.

(laughs)

Polanski knew his audience. He knew what he was

doing, what a film could really achieve.

(pauses)

You know, Gittes’s last line wasn’t in Townes’ final

draft. In the original ending, Gittes was livid,

berating the police, proselytizing justice while

Cross held his dead daughter, the one he fucked and

fathered another daughter with. In the original,

Gittes was real passionate about calling out

authority. He was angry and relatable. He was a

hopeful kind of fiction.

(pause)

But you’ve seen the movie. You know how it really ends.

(pause)

“As little as possible.” That’s the kicker right there.

That’s the tagline of this whole damn thing. That’s

the most real line I’ve ever heard in a film. Because

men can be broken. Gittes gets broken. The system

gets broken. And nobody cares enough to try to fix

it or the people it breaks. They just want their

money. They just want their stories.

It’s dark now. As we PULL BACK, as we RISE UP, REVEAL that trillion-dollar landscape built on stories: Bel Air, Pacific Palisades, Malibu, and Santa Monica; Hollywood, Pasadena, and Burbank, and the vast Pacific Ocean, which SCINTILLATES like broken glass, WINKING at us before it FADES beneath a blood-colored sky.

CUT TO:

*

BLACK and no credits. (No one will take credit.)

It is easy to rage over the inability to forget.

To do as little as possible.

I am a multi-genre writer and filmmaker who was assaulted off of the number one sitcom in the country and went on to pursue an MFA to unwrite and unteach the toxic Hollywood narratives. My work can be found in more than two dozen journals. Recent publications include cream city review, PRISM international, Monkeybicycle, The Rupture, and Pithead Chapel. I have received a Glimmer Train Award for New Writers, AWP Intro Journal Awards, and Pushcart Prize nominations. My first collection of stories, The Year of the Monster, is forthcoming from Unsolicited Press.