Hi

By Rachel Rodman

“I’m just saying. I’m a nice guy. I just want to say HI. And you’re going to accept this greeting whether you fucking like it or not.” —Elon James White, from a now deleted Twitter account

“Hi,” he demanded.

He waited, while everyone watched; he waited with a smile, because this awkwardness was his power, his, his, his.

And something else for me.

But I did not give it. Still I did not give the “Hi” that was owed, though I knew that it was the custom here, to smile for men when they told you to.

A smile that was something else to you.

I had been here long enough, so I did know.

But I was not from here.

“Take me to your leader,” I had said, the first time we had spoken. When I had missed my sisters so much, so much—already, I had missed them so much—though not as much as I would come to miss them.

“Your leader?” he’d said.

“Your leader,” I’d affirmed. I had spoken very badly then (far less well than now). That had been weeks before, right after I had arrived, and I had not yet learned.

“You’re looking at him,” he’d said.

“I do not think so,” I’d said, and the way I spoke was very bad. I would piece this together afterwards, just how badly I had spoken, how badly I had taught myself, even with the assistance of the computer in the cryogenics chamber.

“You’re looking at him.”

“I do not think so,” I’d said again, and the way I spoke was still very bad. I would understand even more how badly later, because he would volunteer to teach me that: the meaning of shame.

Even though he was not a shipboard dictionary.

In my homeland, I had known about leaders. I’d required no shipboard dictionary to learn how to identify them. But I’d known very little about what a teacher was.

So I let him teach me.

I had, however, come to this world for the purpose of reconnaissance. I had come to analyze the air and water. I had come to make maps. As I worked, I also came more and more to correct my most serious misapprehension upon landing: that there was a leader, somewhere, to take me to.

In reality, it was not that kind of world.

So in time I regained my focus. In time, I stopped attending his lessons—the private ones that, in the beginning, he’d insisted were essential.

By that point, in any case, I thought I’d learned enough about shame.

But he’d continued to seek me out in public places, wherever I went to make maps, and he found other ways to teach me.

Initially, I was even astonished by the nuance of these additional lessons: how powerful shame can be. How, in particular, by exploiting an audience, he could shame me into submitting to him.

After a long, lonely, empty journey between the stars, I had also been confident in my understanding of space. (I was intimately aware, in particular, of the effects that one might have on space by passing through it.) But he did things to space that I had not previously understood to be possible: legs spreading to possess more of it (though it was more than that); arms spreading to take the rest (though it was more than that). “Manspreading,” the shipboard dictionary had called it, at least in certain contexts, and the entry had been accompanied by a picture of a man sitting on a bench in a public vehicle, and doing so expansively.

At the same time, his actions on space also constituted a sort of language, even though the words were few. I could translate it like this:

Validate me.

I knew what it meant now; I understood absolutely. (For not even the shipboard dictionary had been so persistent a teacher.)

Validate me.

Validate me.

So eventually, even in public, I increasingly strove to stop participating.

Even as, with ever increasing passion, he continued to teach me.

“Hi,” he was saying now, and everyone was staring, because I did not answer.

“Hi,” he said, in order to accentuate my noncompliance.

“Hi, Hi, Hi,” he was saying, because now he was going to get his validation.

He always did.

Sisters, I had said, days before, when the nature of these lessons had first begun to do more than wear. Please come, sisters.

It was selfish to ask this.

This was not a good world. Even though the air and the water were good. Even though this would be a good place for our spores to grow.

But this was not a good world.

“Hi,” he demanded.

I was only asking them for me.

With the ansible, I had sent them a message: This is a bad world, the world where I am. But perhaps, if you come…

In the journey, my ship had been used up. Our ships always were, in passages like these. Most of what remained: the computer and the cryogenics chamber, had burned up in the entry, leaving, as was usual, almost nothing.

Just me. Just the ansible. And the capacity to send one instantaneous message.

Perhaps, if we are together…

On this world, it would take many, many, many rotations to grow another ship and more fuel, and perhaps weapons too. (As first conceived, it had not been that kind of mission. First missions never are.) Until then, I had only myself.

I had gone the long way, but now that I had made that path, long and lonely between the stars, it could be much quicker for them, no cryogenics chamber required.

That, at least, could be said of my journey.

Though the way back would be just as long.

It was selfish of me to ask. It was selfish, selfish to ask.

To maroon them with me for so many rotations on this bad world.

Would they come?

“Hi,” he said, and his face was close, and everyone was watching, in this place where people came to sit and where coffee was sold. (I needed coffee, I increasingly found, though I hadn’t on the ship; I needed it to assist my mapmaking.) And the shame—yes—was everywhere, but most of it came from me, from parts of myself that, prior to his lessons, I had not known existed, or ever imagined might be violated.

This was part of the lesson.

Validate me.

Validate me.

Validate me.

He was taking all the space now; he was manspreading, manspreading into it, and, in spite of the familiarity, there was also a nuance to the way he expressed himself that I still did not entirely grasp, even as I increasingly sensed that it lay at the heart of the matter: that he seemed to want it all the more—that he wanted it implacably—precisely because he knew I did not want to give it to him.

Is that what I still needed to learn?

In that moment, however, I sensed something else, something behind me. But in that moment I did not turn.

“H—” he started.

Then, in that public place, all the people were screaming and all the people running, and with the frantic exit of everyone went some of my shame.

At the same time, there was a blast of heat and light. And something else on the wall, too, in place of where he had been—a distributed smear of what had once been him:

Manspreading.

In that smear, that “manspreading,” I recognized a basic misapprehension of the language: subject and object switched, so that it had become something that was done to the subject, rather than something the subject did. The man, in this incorrect interpretation, was not the one who did the spreading, but rather the object that was spread (gory and thin, in this case, and on the wall of a public cafe). This kind of mixup felt familiar to me; it was the sort of error committed by someone who has fundamentally not learned to speak correctly.

It was incorrect.

But not, I thought now, so very shameful.

So I turned. And, as I did, I suddenly apprehended, more profoundly than I ever had before, a feeling that, in the first rotations of my existence, safe in my homeland, I had continuously experienced but had never had any need to express—a feeling that, in part, a long, long journey, alone among the stars, had been required to teach me.

“Greetings,” I said, but not to him.

For my sisters had come.

Rachel Rodman’s work has appeared in Analog, Fireside, Daily Science Fiction, and many other publications. Her latest collection, Art is Fleeting, was published by Shanti Arts Press. More at www.rachelrodman.com.

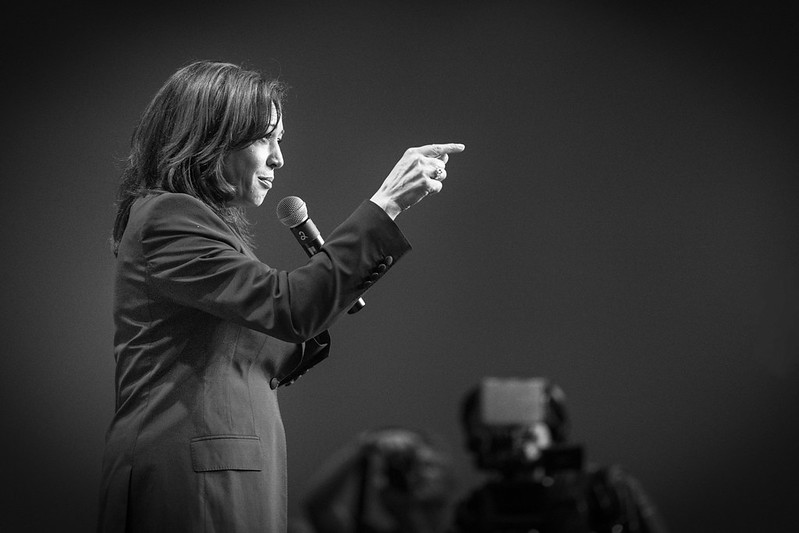

Image credit: By Diario de Madrid for the Madrid Municipal Transport Company, 2017.

A note from Writers Resist

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.