Dispatch from the Holding Tank

By Nancy Dunlop

It is my first day in— what are they calling it? Self-quarantine? Social distancing? Shelter-in-place? I suppose, for me, it’s isolation.

But unlike many others my age, I’ve been in isolation for almost a decade, due to a disability. Today is really no different than any other day for me. Except that I sense other people are also in isolation. So, in some bizarre way I have company.

But when this virus is controlled, when “the curve flattens,” those who are newly self-isolating, and fortunate enough not to get infected, might return to a busy world. A world where people interact. Are productive. Are externally defined.

Another difference between me, an old hand at this isolation thing, and those who are brand, spanking new at it is that I’ve had a long time to deal with introspection. To look inside myself for answers. I had to re-define myself, by myself, from within. But I’m not particularly good at this. I am not good at loss: no more external validation or respect or job title or credentials or any sort of official auspices; no podium, microphone, cubicle, corner office, daily commutes, or jostling for a subway seat to distract me from any need to get quiet and go within.

If you saw my immediate surroundings, you might say, “How perfect for a writer!” The knotty pine cupboards and thick stone fireplace. Those birds racketing out the window. What the sun does to the afghans my grandmother crocheted for me, draped on the back of the love seat. If you could see what I see from my desk. My framed diploma. The photo of Stephen and me at the very moment we were pronounced husband and wife. My two gentle cats, Piper and Chloe. All the things that can bring comfort. Such a perfect retreat for a writer. A writer needs solitude, after all.

But not isolation.

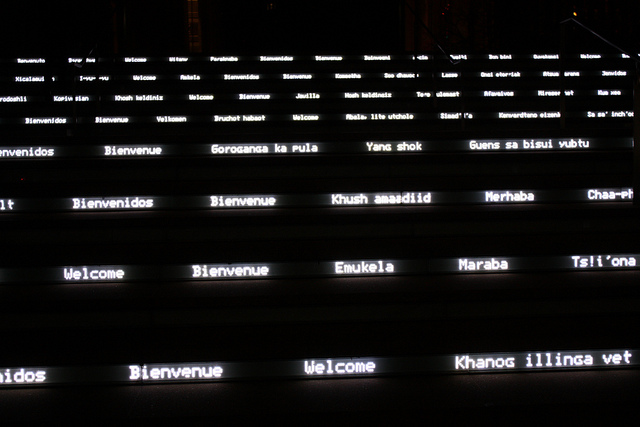

It has taken almost a decade of being by myself to come to terms with being by myself. With my holding tank. So, to the young and healthy I say, “Welcome to the holding tank.”

I am following the news, social media, the stock market, the hoarding-of-toilet-paper and guns. I am following reports of people denying any problem or defying any precautions. And I get it. I know how difficult it is to go from 100 mph to zero. What it is like to hit a wall. To be told that you need to stop everything. That you’re not really essential. Oh, and by the way, nothing will ever be the same.

In the U.S., we’re told that we are a strong people. That we are the strongest people on Earth. We celebrate robustness. Vigor. Movement. Staying busy. Underneath all of that, though? I suspect fear. And anger. And a wicked need to blame. Or to scapegoat. But not a whole lot of anything more subtle or gradated. Like patience. Or acceptance. Or empathy. Not right away. Maybe not ever. Such things take work. Work that doesn’t necessarily look busy.

In addition to being strong, we are said to be ruggedly individualistic. We pull ourselves up by our bootstraps, gosh darn it, and are told to just go for it. Grab that brass ring. We are blasted with seemingly countless opportunities to be on the go.

I’ve noticed this all over social media, a well-meaning impulse to provide ways to stay exactly the way you were before you were isolated. How to work from home. Set up workstations. Put up with your family. Home-school. Learn to draw. Or knit. How to cultivate new interests, immediately. In general, how to stay cheerfully in the world when you are anything but. How to remain unchanging and robust in the midst of a situation demanding change and acknowledging we are not robust.

So, yes, I get it. I understand the sudden burgeoning of tricks and techniques and lists for how to do everything just as before. To do anything but deal with what comes with actual isolation. Like the opportunity—the actual human need—to feel vulnerable. To be soft. Or receptive. Or quiet. To practice not fearing fear. To be kind, despite.

Nancy Dunlop is a poet and essayist, who resides in Upstate New York. She received her Ph.D. at UAlbany, SUNY, specializing in Creative Writing and Poetics. She also taught at UAlbany for 20 years. Most recently, she has been curator of Wren, an international online forum for women in the arts. A finalist in the AWP Intro Journal Awards, she has been published in a number of print and digital journals, including Swank, Truck, The Little Magazine, Writing on the Edge, 13th Moon, Greenkill BroadSheet, and Writers Resist: The Anthology, 2018. Her work has also been heard on NPR.

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash.