Assigned at Birth

By Ellen D.B. Riggle

I needed only search a few minutes to find the aging heavy cardstock piece of paper labeled in block letters across the top, “BIRTH CERTIFICATE.” I scanned a copy of this original document into a PowerPoint slide for a talk I was scheduled to give on so-called “bathroom laws”—legislation restricting who can use which public restroom. To illustrate how my restroom destiny was determined at birth, I clicked on the virtual highlighter button and looked at the picture on the screen searching for my “sex.” Within the faded decorative border is my name, parents’ names, date, time, and location of my birth, and the signature of the hospital’s “duly authorized officer.” In the lower left corner is my tiny baby footprint. However, nowhere is my “sex”—not a prompt nor a blank line. Nothing to highlight.

I checked the original document, thinking maybe this vital information did not scan properly. No, it simply was not there.

In 2016, North Carolina became the first state to pass a bathroom law, House Bill 2 (HB2), restricting access to public restrooms based on “biological sex,” defined as “the physical condition of being male or female, which is stated on a person’s birth certificate.” Although North Carolina was pressured by a coalition of activists and companies to effectively repeal HB2, by early 2025 fifteen states had legislation restricting restroom use based on sex or gender assigned at birth, including two states that have criminal penalties for anyone who runs afoul of the law. Several other states have legislation pending, and current presidential executive orders attempt to regulate access to sex-specific restrooms.

Confused, given the certainty of the legislators in North Carolina and other states that one only need consult the birth certificate to ascertain their sex, I began searching for more information. First, I checked with my brother, born in the same state as I, but in a different year and hospital. His birth certificate decisively declares “male.” Online, I found various images from my home state and others across time, almost all of which included “sex”—although interestingly, not all did.

The birth certificate is far more complex than most people would suspect. In the United States, birth certificates are issued by a variety of sources. Hospitals give new parents, like mine, a fancy piece of paper, sometimes referred to as “ceremonial” or tritely as a “souvenir.” It is not a government document. However, it is (using legal terms) primary, original, direct evidence of the actual birth. This piece of paper is what most people consider to be their birth certificates—especially when that is the title at the top of the document.

A different form, named something like “Registration of Live Birth,” is how a hospital reports to the appropriate county or state agency that a child was delivered alive, and records the date, time, and location (obviously for later astrological consultations), the baby’s name, parents’ names, and maybe other information such as sex and race. The resulting document is issued with an official embossed seal for proving citizenship. I checked the county’s “birth certificate” that I used to obtain a passport in the early 80s, and again found no report of my sex.

Intrigued, I continued searching for my restroom destiny.

Data about births are collected by states and reported to the federal government annually as mandated by the Vital Statistics Act. The federal government agency questionnaire of over 60 items for each birth is a relatively recent invention, and none of the information is mandatory. With no standard national form for birth certificates or registrations of birth, states and localities include different information in their files and create their own documents. Consequently, the National Center for Health Statistics estimates there are over 14,000 different variations of the birth certificate currently found in the United States.

I began to question the implications of this lack of decree of my sex. For example, what would I do the next time I flew through an airport in a state with a so-called bathroom law? What restroom would I be entitled to use? Would I be entitled to use the restroom at all? Would I use the “family restroom” even though I am not a family? Maybe I’ll fly only through airports located in states without such laws?

The legal sex on my driver’s license is listed as F. Seemingly, the DMV accepted my word for it when I turned 16, and it has been so ever since. X has never been an option where I live. Recently I paid for a new copy of what, in my county of origin, is now called a Certificate of Birth. It’s unclear when the certificate form was updated, but on the current version, my sex is listed as “female,” a designation not on prior documents and with no indication of when or how this was determined. In my mind, this is not my birth certificate; it is, at best, a sketchy administrative document of nebulous origin and uncertain validity.

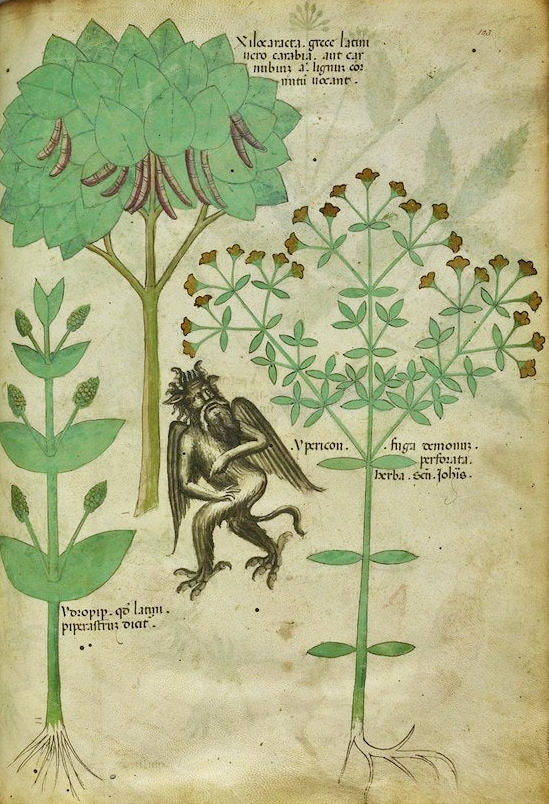

Some legislators seem to have caught on to the birth certificate sex void, because several recent iterations of bathroom bills do not refer specifically to birth certificates but more generally to “sex assigned at birth.” Most legislatures have gone with that vague wording, but Montana lawmakers are quite graphic in their attempt to define sex. “Female” is a human with XX chromosomes and “produces or would produce relatively large, relatively immobile gametes, or eggs, during her life cycle.” “Male” is a human with XY chromosomes and “produces or would produce small, mobile gametes, or sperm, during his life cycle.” This wording ties sexing a baby to an event more than a decade in the future (puberty). Also, I personally find it disturbingly creepy that legislators are talking about human babies the way they do cattle. Perhaps they have forgotten that in the cattle farm economy, producers of small, mobile gametes have little value beyond ending up as a hamburger on someone’s grill.

Where I come from, long before kindergarten we learned it’s not polite to look up girls’ dresses or down boys’ pants. We simply took people at their word they were a girl, boy, astronaut, cute barking puppy, or a scary monster. And somewhere along the way, we learned that adults can be scary monsters, even if they don’t call themselves that.

I called my mother. She reported that in the delivery room the doctor made the classic announcement, “Congratulations, you have a baby girl!” She had never noticed this declaration was not on my birth certificate and was rather amused. I am certain she will not turn state’s evidence if I am arrested for violating a restroom law. Given there is no record of a gene map, nor hormone and hormone receptor test results, and my primary birth document is silent on the subject, I argue my sex is still a mystery.

Other states avoid “sex” by referencing “gender assigned at birth” in their legislation, ironically writing gender ideology into statutory code.

What gender was I assigned at birth? My mother often refers to me as her “awesome daughter.” But her heart and mind are big enough to know that not all daughters are assigned female at birth.

There is an Olin Mills portrait of my brother and me at ages 4 and 2, respectively, wearing matching blue tartan flannel shirts my mother made. Clearly she was enabling my early embrace of flannel lesbian chic. My gender could easily be called Midwest tomboy.

My father more than once referred to me as “he.” We fixed trucks, shot guns, rode motorcycles, and did all the things he would do with a son. In fact, he does have a son. Maybe sometimes in his mind he has two.

Perhaps my gender assigned at birth was never fully ascertained or reliably implemented.

I find a sense of freedom in my discovery that the document labeled BIRTH CERTIFICATE does not declare my sex. I know sex is not determined by a word on a piece of paper, and the simple sex binary is doomed by nature. Gender, often conflated with sex, seems even more complex. However, if we open our hearts and minds a little wider, it’s not so complicated.

One summer day, while standing in the yard talking to my neighbor, her four-year-old grandson looked at me and asked, “Do you have a penis?”

She and I were both caught off guard and smiled. I asked him, truly curious, “Why does that matter?”

He replied impatiently with another question, “Are you a boy or a girl?”

This is a question I had been asked several times before by children his age, usually to the horror of a nearby parent who was obviously afraid of my answer.

“Why does it matter?” I inquired.

“If you’re a boy we can play together,” he declared, obviously hopeful this was the case.

I left it to his grandmother to figure out the specifics of where he learned this rule and conduct a teachable moment.

“I’m neither. Sometimes both. We can play if you want.”

The answer satisfied him. We engaged in a very competitive imaginary car race around the yard, followed by a game of tag, ending with me on my back, balancing him in the air on my feet so he could spread his arms and make airplane sounds.

After a soft landing, he rolled over and put his feet up in the air, offering to lift me up so I could fly too.

Ellen D.B. Riggle is an award-winning educator and author, currently based in Kentucky. They hold a day job as a professor to support a semi-serious hiking habit. Their poems have been published in Rise Up Review, Pegasus, ADVANCE Journal, and Earth’s Daughters, and they are Executive Producer of “Becoming Myself: Positive Trans & Nonbinary Identities” (available free on YouTube).

Photo credit: Joy Gant via a Creative Commons license.

A note from Writers Resist

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.