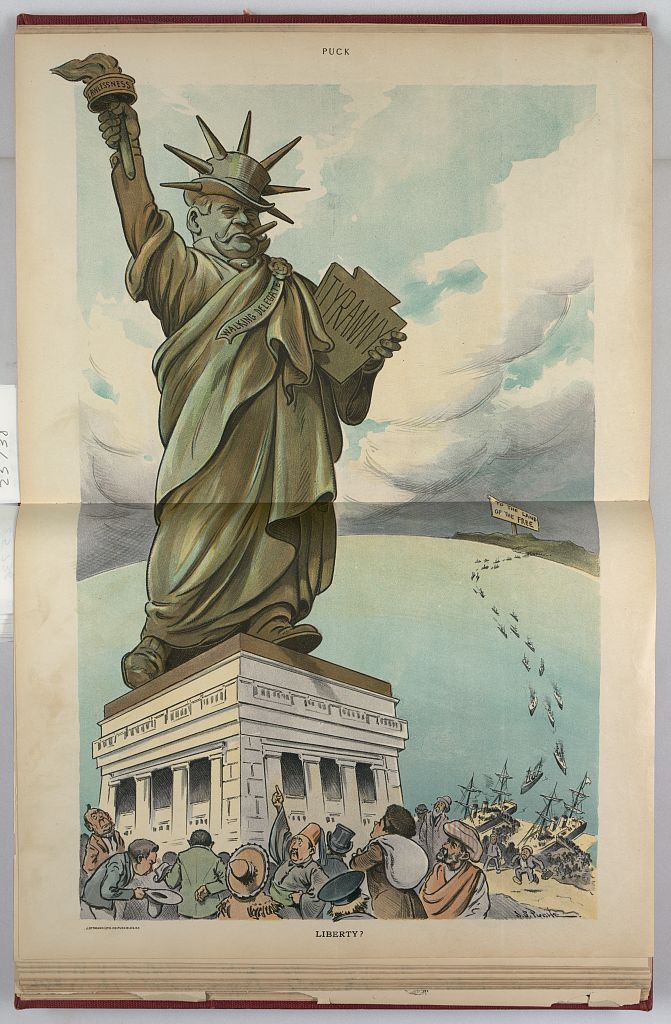

Backyard Musings in America at Twilight

By Ashley R. Carlson

6:52 p.m.

Summer, twilight, after a thunderous lightning-streaked monsoon that flooded streets and yards and sent trashcans floating into traffic-stalled intersections.

Seventy-eight degrees here in Phoenix, uncharacteristically tolerable for the Sonoran desert mid-August.

A breeze ruffles my hair, my German shepherd panting nearby as she lifts her long, jet-black snout to sniff the muggy air, nostrils flaring.

“What a wet summer,” they said earlier today at the tea room. I was the only person inside wearing a mask, save for one employee. We eyed each other across the small shop in solidarity.

Thank you, we said with our gazes, not our mouths, as the other patrons repeated their loud proclamations of “What a wet summer!” nearby.

“What a green summer, you know what that means! The wildflowers will be blooming like crazy next spring!”

But I knew the truth—I’d already read the latest IPCC climate report released August 9, 2021. And it will not mean rain for flowers.

It will mean unexpected, torrential downpours that end up killing four-year-olds seeking refuge on the roofs of their mothers’ cars during flash floods that come raging down from the foothills, washing them away so that their bodies aren’t found until four days later.[1] It will mean record-breaking wildfires that desecrate entire communities and burn hundreds of animals and elderly alive[2]; it will mean increased diagnoses of childhood respiratory diseases and risks of hospitalization and death from those “blooming wildflowers”[3]; it will mean more bleaching events like those that have already reduced the millennia-old Great Barrier Reef by more than half its size in the last thirty years.[4]

It is but a taste—a drop of cream in a teacup the size of Lake Michigan-Huron, a harbinger of the unprecedented (ah, but that horrific word that’s been overused and tarnished and will never not be met with disdain by English speakers again) climate disasters to come.

“What a wonderfully rainy summer!” they sing-songed in the tea room, and I smiled behind my mask and nodded because that’s what you do to be polite.

•

7:14 p.m.

The sky past my backyard is reminiscent of a Rococo.

Taffy-pink melting into periwinkle pinwheels, interwoven by muted grey and dollops of still-receding storm clouds in the hue of what I can only describe as London Fog—the descriptor jumps out to me because that was the name of the tea I bought for my mother-in-law today.

I hear tires on the wet asphalt of the street in front of my house. The distant traffic on the 51 freeway is an ever-present drone, louder now as the final wave of nine-to-fivers (or “seveners”) return home.

A young neighbor calls for their dog a few houses down. An air conditioner on the roof next to mine kicks on, humming good-naturedly.

A bird sings in the tree over my head—chiiiiirp, chiiiiirp, chiiiiirp, chiiiiirp, CHIRP, CHIRP, CHIRP!

A mosquito finds the only uncovered skin on my ankle and sucks, the skin grows itchy and red a minute later and begs to be scratched.

All is well.

All is safe.

There are no armed fighters pounding on my door with my name on a list,[5] ready to haul me away once the international press evacuates and a new crisis gets everyone’s attention.

•

7:37 p.m.

Afghanistan fell to the Taliban three days ago.

Reddit was flooded with news updates and pictures that quickly began trending, garnering 100k+ upvotes and thousands of comments like these:

“I feel so bad for the people who didn’t get a spot on that military plane. Why are there so many men inside and barely any women or kids?”

“Those poor young girls and women. Jesus fucking christ, what they’re going to do to them…”

“Look at the expressions of the people on that plane! The sheer relief!”

“With nothing but the clothes they’ve got on. Left their grandparents and their pets behind.”

I donated and I shared on social media and I emailed my senators and representatives through their website contact forms and received sterile, automated replies back, and then we spent the afternoon sipping tea from tiny cups painted with pink roses, and we talked about the people who’d fallen to their deaths while clinging to that military plane’s wheels.[6]

•

8:02 p.m.

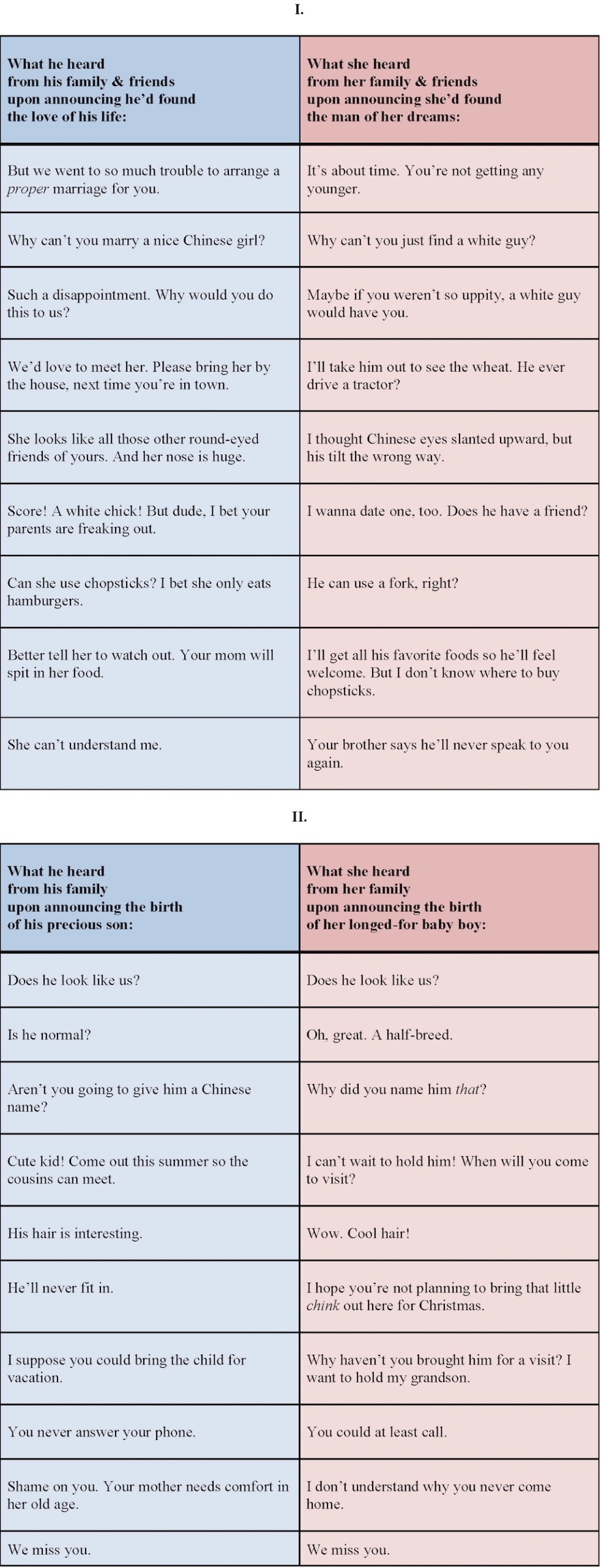

The 2020 census count results just came out—I know because the two middle-aged white women seated beside me in the tea room were discussing them.

“They say the numbers of white people are declining rapidly,” they’d murmured between bites of scones smothered in clotted cream and sips of their oolong tea.

They’d clutched their costume pearls and wiggled their feathered fascinators—all plucked from a box in the corner of the room, beside a cardboard cutout of Queen Elizabeth II.

“They say in a few years white people will be the minority.”[7]

Their eyes were wide, wider than they’d been when the strawberry-and-chocolate-topped petits fours arrived at their table a few minutes before.

What will they do to us? their eyes said as they shoveled the finger-sized desserts into their mouths and plopped more sugar cubes into their steaming cups of oolong.

Nothing that we don’t deserve, was what I’d wanted to reply. I’d wanted to scream it, to swing from the crystal chandeliers overhead draped in multicolored fabric flowers and fake butterflies and fake robins in their fake nests and shriek it in their artificially wrinkle-free faces.

Nothing that they and their parents and their grandparents and their great-grandparents haven’t dealt with every single day of their lives.

Instead I sipped my tea, attempting to swallow a chunk of scone in a mouth that was much drier than before.

•

8:19 p.m.

The author of the book Sapiens says that the current—and only existing—human species of Homo sapiens first evolved 300,000 years ago, positing that they may have forced Homo neanderthalis, Homo erectus, Homo denisova, Homo solensis, and all other human beings belonging to the genus Homo into extinction in the years following.[8]

We’re in the midst of the sixth mass extinction right now.[9]

My good friend, a fellow childfree person, is much more anarchist than I. She often tells me, “Fuck it. Humanity doesn’t deserve to be saved—let us burn. Give the planet back to the animals who deserve it; the ones who survive, anyway.”

I want to be more like her. I’d cry and rage a lot less.

But until that day comes, if ever, I’ll keep donating and sharing on social media and sending emails that my congresspeople will almost certainly never read. I’ll keep crying and raging for the oppressed. For the raped. For the tortured. For the abused. For the left behind. For the traumatized. For the enslaved. For the murdered. For the exploited. For the neglected. And for the silenced.

And I’ll keep writing pointless fucking musings in my backyard in America at twilight.

Ashley R. Carlson is an award-winning writer and freelance editor whose short fiction was selected for Metaphorosis Magazine’s “Best of 2020” edition, and whose nonfiction has appeared in Darling Magazine, Medium, and elsewhere. She’s passionate about animal advocacy and biodiversity protection, the intersectionality between climate and social justice, and fighting against oppression in its myriad forms. She lives in Phoenix with her partner, their three furkids, and an ever-rotating series of foster kittens. Find her at www.ashleyrcarlson.com and on Instagramat @ashleyrcarlson1.

Photo credit: Marco Verch via a Creative Commons license.

Note from Writers Resist: If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.

[1] Brian Webb et al., “Pima Police: 4-Year-Old Girl Who Was Swept Away during Flash Flooding ‘Did Not Survive,’” Fox 10 Phoenix, updated July 26, 2021, https://www.fox10phoenix.com/news/pima-police-4-year-old-girl-who-was-swept-away-during-flash-flooding-did-not-survive.

[2] Hope Miller, “These Are the Victims of the Camp Fire,” KCRA-TV, updated June 17, 2020, https://www.kcra.com/article/these-are-the-victims-of-camp-fire/32885128.

[3] Maria Elisa Di Cicco et al., “Climate Change and Childhood Respiratory Health: A Call to Action for Paediatricians,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 15 (2020): 5344, doi:10.3390/ijerph17155344.

[4] Amy Woodyatt, “The Great Barrier Reef Has Lost Half Its Corals within 3 Decades,” CNN, updated October 14, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/great-barrier-reef-coral-loss-intl-scli-climate-scn/index.html.

[5] Maggie Astor et al., “A Taliban Spokesman Urges Women to Stay Home Because Fighters Haven’t Been Trained to Respect Them,” The New York Times, published August 24, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/24/world/asia/taliban-women-afghanistan.html.

[6] Marcus Yam and Laura King, “7 Reported Dead Amid Chaos at Kabul Airport as Desperate Afghans Try to Flee,” Los Angeles Times, published August 16, 2021, https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-08-16/chaos-panic-kabul-airport-afghans-flee-taliban-takeover.

[7] Hansi Lo Wang, “What the New Census Data Can—and Can’t—Tell Us about People Living in the U.S.,” NPR, published August 12, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/08/12/1010222899/2020-census-race-ethnicity-data-categories-hispanic.

[8] Earth.org, “Sixth Mass Extinction of Wildlife Accelerating – Study,” Earth.org, published August 10, 2021, https://earth.org/sixth-mass-extinction-of-wildlife-accelerating/.

[9] Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens, (New York: Harper, 2015): 21.

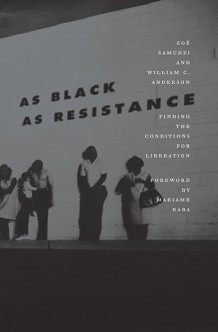

William C. Anderson is a freelance writer. His work has been published by The Guardian, MTV and Pitchfork among others.

William C. Anderson is a freelance writer. His work has been published by The Guardian, MTV and Pitchfork among others.