The Cancer of Misogyny

By Pam Munter

Longtime Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill famously said, “All politics is local.” But for me, all politics is personal, especially when discussing the circumscribed role and demonization of women in society. The current spate of misogyny, with its soaring rise in the public forum, has uncapped an ineptly sealed lid on the sexism that has always been dominant in our society.

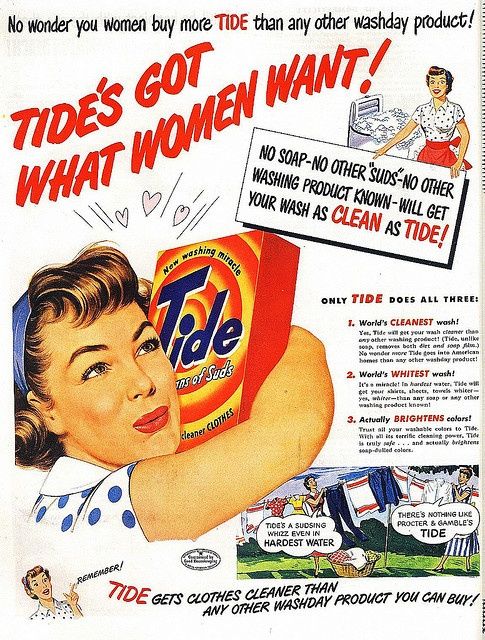

I grew up in a time when white women of privilege were proudly seen as appendages of men, had few legal rights, couldn’t own property in their own name, were unable to adopt as single parents or even have independent credit cards. Comedians—both male and female—evoked predictable guffaws about the cartoonish consensual roles. Women, who inevitably stayed at home with the kids, were seen as shopping-oriented, recklessly spending the husband’s hard-earned money if she weren’t leashed. Women were parodied as motor-mouthed and too emotional. In comedy routines and in the media, women characters were just short of being harridans, commonly viewed as the natural enemy of men. Henny Youngman’s famous quip, “Take my wife … please,” brought roars of laughter from both “henpecked” husbands and the oppressed women who were the subject of the joke. Quips about men related to their domestic coping styles were often restricted to the hostile one-liners husbands used to shut out their talkative wives. It was a matter of human nature, it was thought. Men were stoic, consensually superior—smarter, more accomplished, better educated. Women were helpers, facilitators and, of course, unpaid domestic servants. There was no escaping one’s fate. If women weren’t married by their early 20s, they were “spinsters” or “old maids.” There was no equivalent indictment for unmarried men.

Heterosexual relationships were about seduction, gamesmanship, indirect communication, covert lying. “A man chases a woman until she catches him,” went the clever cliché. Honest disclosures were not prized or common, unless they were inadvertent slips in the heat of anger. The relationship between men and women has been characteristically adversarial and hierarchical.

I first noticed this normal combativeness as a kid, while watching movies and TV. The legendary feminist Katharine Hepburn might have adroitly sparred with Spencer Tracy, but in the last reel, she gave up her whims, acknowledged defeat, and married him. Repetitive plot arcs of the ubiquitous sitcom “I Love Lucy” involved Lucille Ball trying to put something over on husband Desi Arnaz. When he got wind of her schemes, he would nonverbally threaten her with his rage-filled countenance and a raised fist, causing his wife to comically cringe. Ralph Kramden engaged in similar threatening behavior with his wife, Alice, in “The Honeymooners,” all mirrors of the pathology in our culture.

From my earliest memories, I was advised by well-meaning adults to keep my IQ points under wraps and never, ever comment on any of my accomplishments. The conversation should always be focused on the boy. As I grew into adolescence, my mother cautioned me to be careful around boys because “they’ll take advantage if they can. You don’t want to get pregnant.” She made them sound like barely restrained animals, requiring vigilance else I be consumed by their inevitable sexual demands and ruin my life.

Home wasn’t any better. During large family gatherings on holidays, the women would cook all day for the men, then encourage them to eat copious amounts of lovingly prepared food, as if gluttony were a testimonial to their worth as women. As might be expected, conversation at the table centered around the men and their sons. When there was an uncomfortable silence, one of the men would seize attention and tell a joke, a well-timed antidote to any meaningful conversation. After the meal, the women repaired to the kitchen where they cleaned up and often good-naturedly complained about the idiosyncrasies of their husbands. The men moved toward the living room to sit in front of the TV, observing a sports event, intermittently cheering loudly to display their knowledge as if it were admission to a special, secret club.

You can probably tell from this brief summary of my childhood social education that I was angry even then. I didn’t understand why women were complicit in allowing themselves to be the butt of the joke while the only common generic slam against men was their unwillingness to ask directions when lost, a poke always done with levity. In fact, the sex wars were always painted with humor, as if a light touch would cover the sense of umbrage and pique lurking just below the surface. I knew then that I would not be like them—not like the women and not like the men. I would have to chart my own personhood even with the disappointing dearth of role models. It would be my responsibility to search and reflect, constructing and assembling the values and beliefs that fit who I was and who I wanted to become. That meant risking going against the norms, engaging in dangerous rebellion that often brought me in conflict with authority.

While in high school, I didn’t use illegal drugs or drink too much, didn’t get in trouble with the law, didn’t drop out of school (though I briefly considered it as a junior in high school). My mouth got me in trouble often enough with my “inappropriate” questioning while actively challenging the sex-role rules. For me, however, it turned out that the best way to resist the misanthropic status quo was through education, choosing fields that were unusual for a woman at that time. My family—especially my tradition-bound mother—and teachers often sought ways to warn me about what might lie ahead. Early on, any act of rebellion was met with, “Girls shouldn’t/can’t do that.” When I followed my dreams through education, I was advised, “You’ll price yourself out of the market. Men don’t like women to be smarter than they are.” The implicit message was, you don’t have value unless you are with a man.

In fairness, men were schooled in the same rigid ways we were, even though they had more behavioral latitude. They, too, were modeled after two-dimensional stick figures, and provided an unwritten list of desirable characteristics for manhood. “Locker room talk” was a tribal merit badge, a way to bond with other men, reinforcing their sense of supremacy over women. The male teenager’s goal was demonstrable macho dominance and sexual conquest. For women, the list of “desirables” was headed by compliance and deference. As we know, it is extremely difficult to undo early training, especially when it’s universally reinforced.

The 1960s was the decade in which I reached adulthood. It coincided with the dawn of the second wave of public feminism. As a result of a series of lawsuits, a new generation and the morphing of society, women began approximating the rights and privileges of men. Evangelical groups ranted about “permissiveness” and the threat it represented to the hallowed family unit as women evolved into the workplace. But then, there was a stronger boundary between church and state than there is now.

Although I was teaching political science at a university in the 60s, I joined in the fray, ran “consciousness-raising groups” and even marathons to help women rise above the oppressiveness. Much later, when I earned a Ph.D. in clinical psychology and taught at another university, I instituted a Psychology of Women class and served as a mentor to students, both male and female. It was a time when women were exerting their power, perhaps for the first time. Though I was the only full-time female faculty member in the psychology department, I carved out a small niche where my feminism and political activism were “allowed” by the men. And in my clinical private practice, I enjoyed working with both genders, helping to release them from the institutionally imposed limitations.

Another topic, essential but perhaps the subject of another essay, are the significant dues paid by those of us who realized we are LGBTQ. It is only marginally safe to identify with this group now; in the 1940s and 1950s it could be a lethal choice, both figurately and literally. There was only one mainstream and those who did not conform were ostracized and far worse.

Just when we were all thinking there was progress on these fronts, along came the election of 2016. Trump’s “Access Hollywood” tape and his repeated pejorative remarks about anyone who did not worship him were warning signs that obviously went unheeded. He was elected, not in spite of his womanizing, but because of it. He was a “man’s man,” conquering all in his wake. What happened? This is a complicated question and not the subject of this essay. The point here is that some things have not changed. At the head of our government is a man who espouses those toxic, anachronistic 1950s values about the roles of men and women. On the plus side, his loose-cannon tenure has inspired the #MeToo movement, along with overdue revelations about men in power who routinely victimize women. Trump has selected mostly white men as his sycophants, those who reflect his provincial and barbaric values. Who knew there were so many Trump clones in public service? And such a wellspring of misanthropy?

I am very fortunate that I have never been a victim of physical violence. However, chronic indignities, ridicule, blocked professional advancement and bombardment by derogatory jokes on a daily basis affect one’s life, too. What strengthens us is self-esteem, and we cannot delegate it to others, even to well-meaning people. Doing so renders you vulnerable and drains your power. The most predictable and efficacious means of resistance to sexism is to build an internal self and develop trust in your own judgment, giving you the confidence to assertively address sexism whenever and wherever it appears.

Because I am in a late decade in my life, I have a longer-term view. My perspective, of course, is limited, coming from a privileged white woman’s perspective. Women of color and others relegated to the fringes of society are victimized many more times than I was and in different ways. But the relentless malignancy touches us all. There is no escape. Having lived through familiar oppressive times for women, I am saddened and angry that this cancer has found renewed footing in our culture. I no longer march in the streets, but I can write a check to organizations that support equal rights and to candidates who advocate for women’s equality. I can write letters, send emails, call lawmakers. It’s not enough, but it’s what I can do. We can never eradicate this pernicious virus completely. Like a cancer, it will only go into remission, emerging again when permission is implicit.

Pam Munter has authored several books including When Teens Were Keen: Freddie Stewart and The Teen Agers of Monogram (Nicholas Lawrence Press, 2005) and Almost Famous: In and Out of Show Biz (Westgate Press, 1986) and is a contributor to many others. She’s a retired clinical psychologist, former performer and film historian. Her many lengthy retrospectives on the lives of often-forgotten Hollywood performers and others have appeared in Classic Images and Films of the Golden Age. More recently, her essays and short stories have been published in more than 90 publications. She is the nonfiction book reviewer for Fourth and Sycamore. Her play Life Without was a semi-finalist in the Ebell of Los Angeles Playwriting Competition and was nominated for the Bill Groves Award for Outstanding Original Writing, along with a nomination for Outstanding Play in the Staged Reading category. Her second play, That Screwy, Ballyhooey Hollywood, will open the new season for Script2Stage2Screen in Rancho Mirage, CA. She has an MFA in Creative Writing and Writing for the Performing Arts. Her memoir, As Alone As I Want To Be, was published by Adelaide Books in October 2018. You can find much of her writing at www.pammunter.com.