War Ghazal

By Linda Laderman

Again, we witness panicked people fleeing war.

You tell me, people don’t care, it’s Ukraine’s war.

Sitting in an Ann Arbor bistro, we order baked Turkish eggs,

& I mumble, even Turkey opposes this war.

One booth over, a woman applies siren red lipstick,

then gestures at the screen over the bar. A televised war.

Empty trains rumble down tracks outside the restaurant.

The chef rings a bell. Everyone cheers, detached from war.

At Costco, gas lines stretch into the street. A driver

hollers to the car behind him, price gouging, a gas war!

A man in army fatigues stands outside the corner CVS,

hawking Ukrainian flag pins. He shouts, no more war.

Down the block, neighbors discuss Ukraine’s desolation.

Isolated in a hospital basement, patients huddle. Pawns of war.

You switch on news of war-weary crowds cramming trains.

I shut it off. Suspended in silence, the distant din of war.

In an ordinary neighborhood, a mother, her children lie dead.

What more do we need to know about this fucking war?

Pleas for ammunition, boots on the ground, a no-fly zone.

We send sanctions & drones. Ukraine, it’s your war.

Babyn Yar, 33,771 Jews murdered by bullets in a Ukrainian ravine.

We agree Zelensky, never again! Still, fire fuels a madman’s war.

Linda Laderman grew up in Toledo, Ohio. She earned an undergraduate degree in journalism from the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism at Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. Her news stories, features and poetry have appeared in media outlets, magazines and literary journals, most recently in 3rd Wednesday Quarterly of Literary and Visual Arts and The Scapegoat Review. She returned to school in the 1990s, graduating with a Master’s of Liberal Studies and a Juris Doctor degree from The University of Toledo. Linda currently lives in the Detroit area. For the last decade, she has volunteered as a docent at the Zekelman Holocaust Center, and recently gave her time as a writer and case screener for the Wayne County Detroit Conviction Integrity Unit.

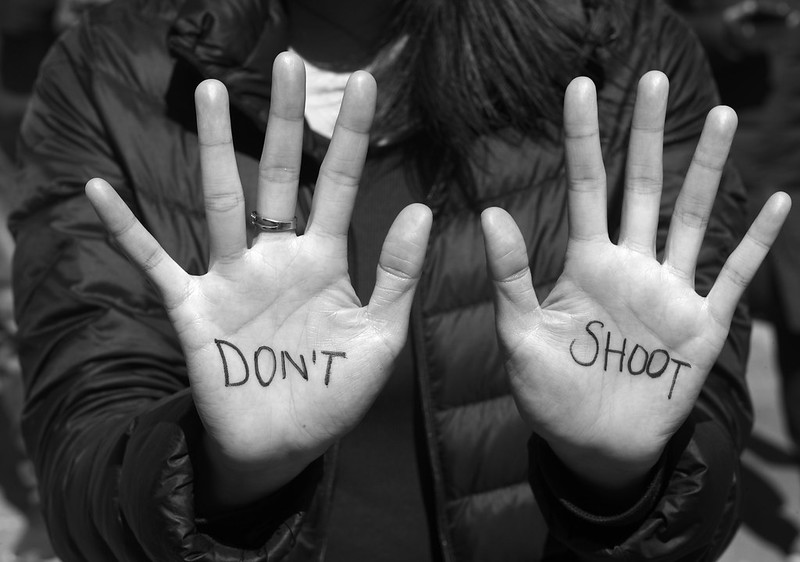

Photograph by manhhai via a Creative Commons license.

A note from Writers Resist:

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.