Two Poems by Alice Rothchild

[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” hundred_percent_height=”no” hundred_percent_height_scroll=”no” hundred_percent_height_center_content=”yes” equal_height_columns=”no” menu_anchor=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” enable_mobile=”no” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_mp4=”” video_webm=”” video_ogv=”” video_url=”” video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” video_preview_image=”” border_size=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” margin_top=”” margin_bottom=”” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=””][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ layout=”1_1″ spacing=”” center_content=”no” link=”” target=”_self” min_height=”” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” class=”” id=”” background_color=”” background_image=”” background_position=”left top” background_repeat=”no-repeat” hover_type=”none” border_size=”0″ border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” padding=”” dimension_margin=”” animation_type=”” animation_direction=”left” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_offset=”” last=”no”][fusion_text]

Thoughts on walking by rippling grey water under a darkened sky

In the days before stretch marks,

second husbands,

morning stiffness,

encore careers.

In the days when we couldn’t imagine

finding weed and condoms

secreted under our teenagers’ beds.

Or knowing the location of

every hidden bathroom in innumerable coffee shops,

Whole Foods,

Farmers’ Markets.

In the days when we wore clunky platform heels and

mini-skirts,

tossed a lion’s mane of crazy hair,

never worried about bunions,

hammer toes,

aching knees.

In those days,

poetry spilled from our guts,

orgasms came easy.

The spirit songs rooted

in our less encumbered selves,

wended their ways to our melodious, defiant tongues,

buoyed by a million women marching,

bearded men burning draft cards,

the fervent possibilities of youth.

Now, even in our graying successes,

we are weighted by the stones

of our disappointed mothers,

of bruises and torn ligaments accumulated

by stumbling through life.

Now, the future has creeping limits.

We’re stalked by the next mammogram,

unrelenting cough,

crushing brick on the chest.

Now, we have silver haired urgency

nipping at our toes.

This is an old fashioned

Call to action!

Take heart.

Wear purple.

Poke amongst old embers.

Your sisterhood will hold you.

When you are drowning,

we will throw you a life raft.

When you are gardening,

hand you a hoe.

If you fall into a hole,

we will haul down a ladder,

bad backs and all.

But when you are singing,

we will dance

Within reason.

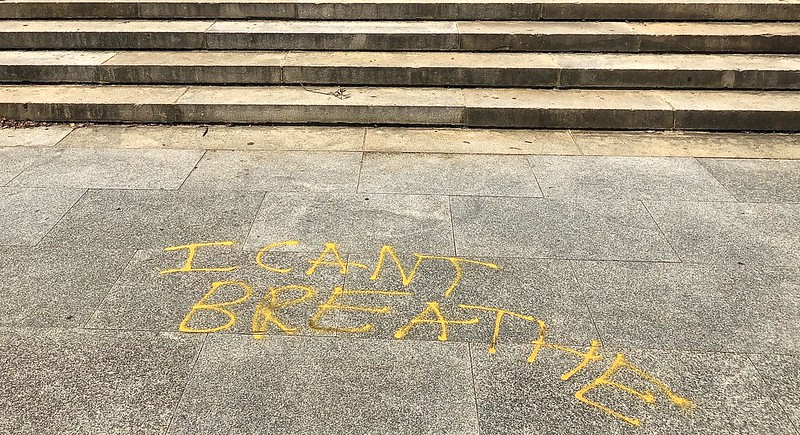

The Right to Choose

December 30, 1994

Brookline, Massachusetts

On December 29,

twenty-two-year-old John Salvi,

thick black hair,

a wisp of a mustache,

eyebrows that knitted together

over the bridge of his nose,

drove to a hunting range

to practice his aim.

The following day,

less than two miles

from my home,

on a crisp, subzero morning,

forty pregnant girls and women,

partners, friends, mothers,

anxious, sad, frightened, resolved,

waited in a Planned Parenthood Clinic

for their turn.

Salvi strode into the clinic

carrying a black duffle bag.

If anyone had been watching,

they would have heard the quiet buzz

as he opened the zipper,

removed a modified .22 caliber Ruger 10/22 semi-automatic rifle.

He hit the medical assistant, Arjana Agrawal,

in the abdomen,

killed the receptionist, Shannon Lowney,

with a shot to her neck.

Screaming, blood,

a scramble for safety.

a shower of bullets,

five wounded.

He took his gun,

sprinted to his Audi,

drove west on Beacon Street

to Preterm Health Services,

two miles away.

Salvi strode into the clinic,

asked the receptionist, Lee Ann Nichols,

“Is this Preterm?”

Shot her point blank with a hunting rifle.

A security guard, Richard Seron,

returned fire.

Salvi dropped the duffle bag

containing receipts from a gun dealer

in Hampton, New Hampshire,

plus seven hundred rounds of ammunition and a gun.

He fled south to Norfolk, Virginia,

was captured after firing over a dozen bullets

into the Hillcrest Clinic.

The police arrived at Preterm

five minutes too late.

I trained before abortion was legal,

cared for women,

traumatized, mangled, infected,

by back-alley procedures.

I was an abortion provider

at the Women’s Community Health Center

and Beth Israel Hospital,

ten minutes from Planned Parenthood.

The next morning,

my eleven-year-old daughter

asked me, as I left for work,

“Mommy, are you going to die today?”

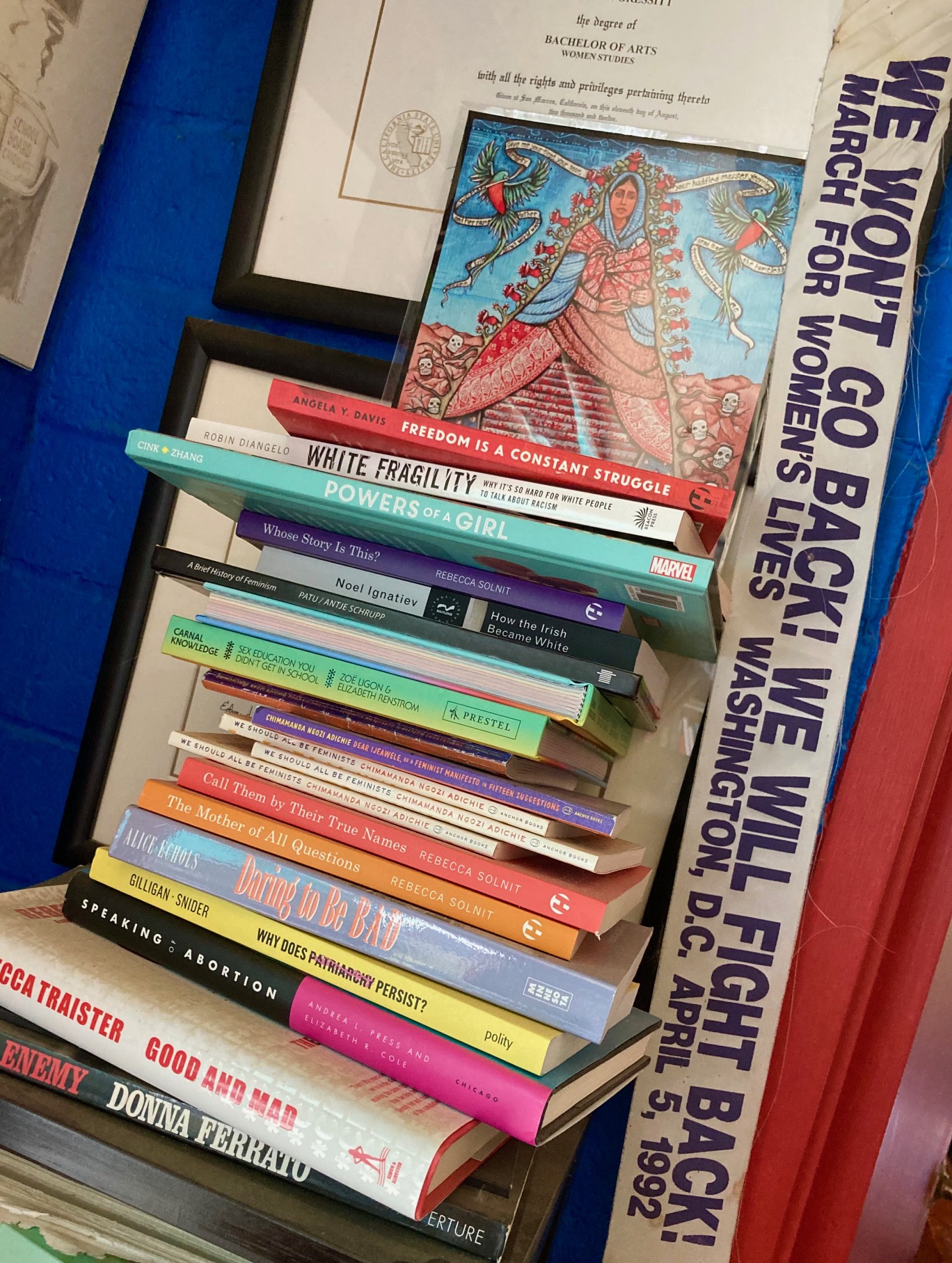

Alice Rothchild is a retired ob-gyn, author, and filmmaker who is writing a memoir in verse for young adults exploring her childhood in the 1950s and 60s and her development as a feminist physician and activist. Her poetry appeared in a collection of poems and essays titled Extraordinary Rendition: (American) Writers on Palestine. Her other published nonfiction books and contributions to anthologies, blogs, and webzines are listed on her website: alicerothchild.com. She is inspired by the unheard and the forgotten, the awakening of women’s voices and truth telling in the twenty-first century.

Photo credit: K-B Gressitt.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]