Post-Election Meltdown

By Marcella Remund

I am 60 years old. In my lifetime,

my mother’s lifetime, and all the

lifetimes that came before,

no woman has been president.

Don’t tell me to get over it

I have TRAINED blonde footballers

for jobs I couldn’t get without a penis,

jobs that paid ten times my single-mom

salary. After 40 years, I still must work

harder, longer, sweeter to make less.

I have been the “chick in the band.”

I am afraid to go out alone at night.

To walk alone, eat alone, travel alone.

I have been targeted as a child, nine

months’ pregnant, wrinkled and old.

Pedophiles picked me out at 7, at 13.

Don’t tell me to let it go.

I have worked since I was 14.

So has my mother, who worked

two and sometimes three jobs

until she was 70, so had my

grandmother, both of them always,

always, still expected to keep a clean

house, put dinner on the table, pay

bills, keep four kids quiet.

Don’t tell me to move on.

I have daughters, daughters-in-law,

granddaughters, nieces, girl cousins,

sisters-in-law. Their world will go on

just like before, unequal, unsafe, unjust,

until those men are gone—you know

who they are—and worse:

they will inherit a tanking economy

for all but billionaires, greed and profit

our national anthem, international

isolation in our buffoonery, and worse:

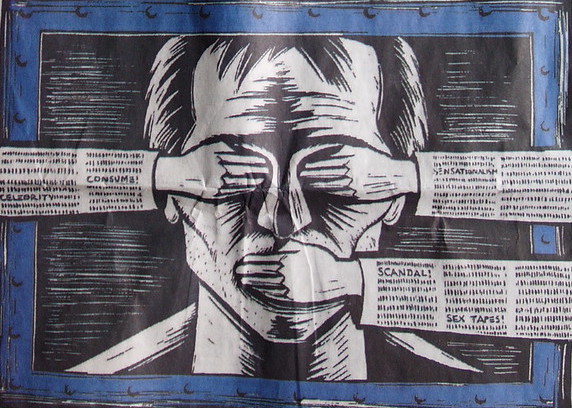

open, ignored, sanctioned hatred

and humiliation aimed at my non-male,

non-white, non-Christian, non-straight,

othered friends & family (and yours,

because you have them too).

The list of damages goes on and on.

Don’t tell me we have other work to do.

I have earned this anger.

DO YOU HEAR ME?

Don’t tell me not to feel this grief,

this disbelief, this loss of faith.

I will open my heart and my home

to those who are terrified, paralyzed,

hopeless. And I will move on,

get over it, let it go when I’m

goddam ready. Until that moment,

I will keep screaming

NO.

Marcella Remund is a native of Omaha, Nebraska, and a South Dakota transplant, where she teaches English at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals. Her chapbook, The Sea is My Ugly Twin, was published in 2018 by Finishing Line Press, and her first full-length collection, The Book of Crooked Prayer, is forthcoming from Finishing Line in 2020.

Photo credit: The sculpture, “Innovation,” is by artist Badral Bold, made with horse tail. It is photographed by Frank Lindecke via a Creative Commons license.