Who We Are, More or Less

By Rasmenia Massoud

There’s no telling how long his 15 minutes are gonna last.

His raincloud-gray eyes stare out from thumbnails and video clips in news feeds. They’re surrounded by white impact font, memeified versions of him coming in from the left and the right. There he is. The conservative news hero du jour. The vigilante. The patriot. The murderer. Eddie.

Fucking Eddie. His back ramrod straight, his nods stiff and rigid as though that shiny blue necktie is the only thing keeping his bald head attached to his thick neck. The chyron at the bottom of the screen below his grin says he’s Edward now. All grown up. All business. All American flag pin stabbed into his lapel.

Anyone who knows how to look can see the skinny kid with a mullet and weak attempt at a moustache cowering beneath the surface. Anyone who grew up in our little Idaho town that no one else ever heard of. Anyone who was drinking Mickey’s Big Mouth around a bonfire at the reservoir when our soundtrack flipped from Mötley Crüe to Alice in Chains.

Another moment that didn’t seem relevant until it was gone.

The news personality leans in to show sympathy for Edward’s harrowing ordeal. Not a hair out of place in her crispy platinum mane. The defender of his neighborhood, Edward talks about his pride in the Minneapolis suburb where he grew up. Except he didn’t. Well, Eddie didn’t anyway. There are brief flashes where he seems like a different person, but as I lean on the table to close the distance between my eyes and laptop screen, I see that there’s just more of him now. The added flesh around the neck and eyes, the meaty arms and torso. Life and time have added layers, pushing that kid I once knew farther down.

I rub the thick scar tissue on my chest, a habit I developed after the double mastectomy. A transparent reflection of my face is a ghost hovering over Edward’s on the laptop screen. My hair is cropped short, the warm blonde morphed to shimmering strands of silver. Edward’s been piling on protective layers, becoming more visible. Stacking them up until he fills a TV screen. Me, I’m shedding them, cutting things away, fading to colorless invisibility. Distilling down to the essence of a person.

The blonde woman behind the desk blinks her heavily painted eyes. False lashes fluttering and pencilled brows furrowing to show the audience how serious, how life-and-death Edward’s experience was. Edward recounts the series of events. He talks about his neighborhood, his family, his unwavering belief that America is still the best country in the world, despite how bad things have gotten.

What he doesn’t say is the name Marcelo Chavez. Neither Edward nor the sculpted on-air personality mention that Marcelo was only 15 years old. It never comes up, how the kid was walking home from a babysitting gig when he dropped his phone on the sidewalk, at the foot of a driveway. Edward’s driveway, where he parked his precious SUV. What Edward tells the woman, and the rest of the viewing audience, is that the boy appeared to be messing around with his vehicle. Maybe vandalizing, slashing tires, siphoning gas, or worse. Who can tell these days? When Edward stepped out of his house, aiming toward the trespasser, Marcelo made the mistake of raising his hands while holding his phone and having skin a shade too dark for that particular corner of the city.

Edward at fifteen had been as awkward and gangly as Marcelo Chavez. At sixteen and seventeen, he started to grow into himself, taller and thicker, a brush of brown-blond hair beginning to appear above his upper lip. No matter how deep I plunge into the murky depths of my memory, I can’t recall when he’d begun sticking to the edges of our friend group. He was a few years younger than me, not someone I paid much attention to. But Eddie made his presence known. Younger and goofy, sure, but he had more confidence than he’d had a right to.

The skunky smell of weed mingled with the pine smoke. A crackling bonfire, popping wood, whooping, and chattering from all the shaggy-haired kids clad in denim and threadbare band shirts. Strawberry blonde down to my waist, c-cups beneath my Guns n’ Roses Use Your Illusion t-shirt, dancing and singing along with Tesla about signs, signs, everywhere the signs with my bottle of Mickey’s when that kid hovering in my periphery was right in front of me. Right in my face.

“Dude. No. I have a boyfriend,” I said. My boyfriend, what’s his name, who was old enough to drive and buy beer. Also, old enough to hang out at strip bars while I drank cheap malt liquor with the rest of my underage friends at the reservoir.

Eddie stepped closer until we were nose to nose, smirking. “Yeah?” He looked around. “Where is he?”

That confidence was five sizes too big for Eddie, but he wore it like a second skin and that was enough. That’s all it took. A few days later, we’re rolling around naked and sweaty in a bedroom that belonged to neither one of us. That’s when his protective armor left him, when I saw beneath and looked into the eyes of an insecure young man who desperately did not want to be seen.

“Were you a virgin?”

He glared at me. “Of course not. Why? Was it not okay?”

“It was fine.”

“No really. If it wasn’t okay, tell me. I can take it.”

I knew better. He couldn’t take it.

“It was fine. Really,” I said.

“Just fine?”

Now, on my laptop screen, that insecure kid is in there somewhere. Like a matryoshka doll, the years of doubt, decisions and bad habits all wrapped around and around until Eddie is concealed forever.

Somewhere behind me, Lupita tells our son to brush his teeth before bed. I inhale the smell of dish soap and eucalyptus as she sits at the table next to me, leans in and turns my face to hers. She kisses the tip of my nose. Her big dark eyes glistening like they always do, hair tucked up in her silk scarf so that I can see her entire face. The dimple on her left cheek, and the freckles dotting her nose. Somehow, she glows brighter more and more with every passing year.

Then my wife closes the laptop.

“You need to stop watching this.”

“I know. But I’m stuck on the fact that we came from the same time. The same place.”

“He’s not the person you used to know. You’re not the person he knew. People change. It happens to all of us. That time and place is gone.”

I want to tell her people don’t change. They evolve and erode. They become more or less of who they are. I don’t say any of this. Instead, I push my chair away from the table and take her hand. “C’mon,” I say. “Let’s go tuck him in.”

A daily, mundane thing, the bedtime ritual of telling our son goodnight. A tiny thing that might not seem relevant until it’s gone.

Rasmenia Massoud is the author of three short story collections and several stories published in places like The Sunlight Press, XRAY Lit, and Reflex Press. Her work has been nominated for The Best of the Net, and her novella Circuits End, published by Running Wild Press, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2019. A second novella, Tied Within, was published by One More Hour Publishing in 2020. You can visit her at www.rasmenia.com.

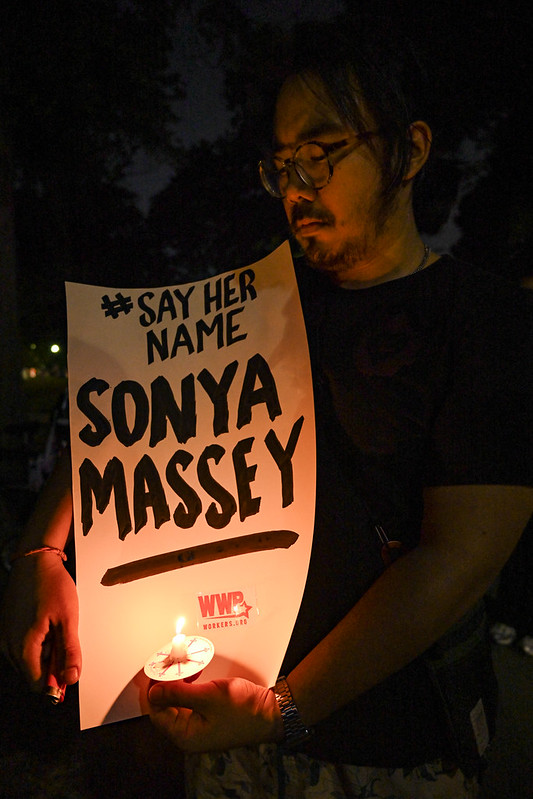

Photo credit: Joe Wolf via a Creative Commons license.

A note from Writers Resist

Thank you for reading! If you appreciate creative resistance and would like to support it, you can make a small, medium or large donation to Writers Resist from our Give a Sawbuck page.