Milk Duds

By Marleen S. Barr

Baby cages were the last straw for Professor Sondra Lear, a feminist science fiction scholar par excellence. She had tears in her eyes whenever she thought about children wrenched from their parents’ arms. Desiring to drown out her sorrows in a morning cup of coffee, she boiled water and placed a skimmed milk carton on her kitchen table. There was nothing unusual about the boiling water. Not so, the milk container. It disappeared. A person-sized breast leaned against the table in its place.

“Okay, I get it,” said Sondra to the breast. “You’re a graduate student engaged in a publicity stunt to garner interest in a Philip Roth memorial event. Great idea to dress up as the sentient breast protagonist in Roth’s ‘The Breast.’ Wonderful breast costume.”

“I am not a costume,” responded the breast.

“Enough already. You can come out of character. I will attend the memorial service.”

“I am a breast.”

“Are you making a #MeToo statement against the harassing male professors in the English department? Attending a department meeting dressed as a breast would be a good protest strategy.”

“Professor Lear, you are a feminist science fiction scholar. You must believe me when I state that I am a breast.”

“I’m open to believing you. But what are you doing in my apartment?”

“I have come to Earth to help the immigrant children Trump is imprisoning. In order to be effective, I need your cooperation.”

“Why?”

“I am a denizen of the feminist separatist planet Mammary. Mammarians patrol the galaxy in search of children whom fascists victimize. Our Maternal Council mandates that we must work in conjunction with at least one native of a planet that requires our intervention. Are you on board?”

“Yes. Certainly.”

“Good. My name is Lactavia. Since I would cause a ruckus if I bounced along Manhattan streets, I would like you to drive me to the Lincoln Tunnel’s entrance.”

“Glad to help. But please understand that I need to cover you with a trench coat. I live in a conservative New York co-op apartment building. I don’t what to incur the wrath of the co-op board. Even though New Yorkers keep to themselves, you would be beyond the co-op pale.”

Sondra drove to the Lincoln Tunnel with the trench coat-shrouded breast in tow. She parked and waited after Lactavia exited. Lactavia knew that Air Force One had landed at Newark Airport and Trump and his daughter Ivanka were en route to Trump Tower. When the president’s motorcade emerged from the tunnel, Lactavia positioned herself in the middle of the roadway.

“I have to stop the car,” said Trump’s driver. “We are being blocked by a huge breast.”

“Huge? Huge is priority one in relation to breasts,” Trump said. “But huge or not, breasts do not belong in the street. This must be some sort of feminist protest stunt trap. I’m not going to be stopped by fake news publicity. Keep going!” he bellowed as he looked out the window. “Wow. Big tit. Bigger than Melania’s.”

The limo full frontally hit Lactavia and bounced back. A cascade of milk emerged from her nipple and turned the black limo white. Before the Secret Service agents could stop Trump, he bounded out of the limo and confronted Lactavia.

“I won’t be intimidated by no huge tit.”

Milk covered Trump to the extent that he appeared to be white instead of orange. He was whiter than the homogenous population of Russia.

“People know about your Russian hotel golden shower. Now meet your white shower,” said Lactavia.

“This is a witch hunt,” screamed Trump as he wiped milk from his eyes.

“On the contrary, I am engaged in a fascist monster hunt. I am a feminist extraterrestrial charged with hunting down fascists who hurt children. I am here to close down your baby jails and rescue the children who are suffering for your political benefit.”

Sondra, risking a parking ticket, left the car and walked toward Lactavia and Trump. “I am Professor Sondra Lear, a feminist science fiction expert. You are closely encountering an all-powerful alien from the planet Mammary. It’s in your best interest to do what she tells you.”

“That tit alien is a rapist,” shrieked Trump. He slid his hand inside his oversized suit jacket, drew a gun, and shot Lactavia. The bullet bounced back and fell harmlessly to the asphalt.

“Okay, ya got my attention,” said Trump, as Ivanka stepped outside the limo. “Ivanka, meet an extraterrestrial from Mammary.”

“Daddy, I’m scared,” Ivanka whimpered as milk drenched her. “The milk is ruining my outfit and getting my hair wet. I had a bad hair day yesterday. I can’t face another. Do something!”

“You’re supposed to champion mothers,” said Sondra. “Don’t you like milk?”

“I like my appearance and my brand.”

“Why aren’t you doing something to help the imprisoned children? I will echo Samantha Bee: You’re a ‘feckless cunt,’” proclaimed Sondra.

Ivanka jumped into her father’s arms.

“This isn’t such a bad day,” he said. “I get to grope my daughter and ogle a huge tit.”

“Oh no, you are not,” Lactavia said. “I am going to remove your daughter from your custody.”

“On what grounds?”

“You are illegally crossing the border separating New Jersey from New York. You are subject to arrest. You have to turn your daughter over to me.”

“There’s no such law.”

“I just made it up. I can enforce whatever law I want. I am more powerful than you.”

“Ivanka,” said Sondra, “I suggest that you detach yourself from your father immediately, if not sooner.”

“Daddy, Daddy, help! I don’t want to go god knows where with an extraterrestrial breast. If the alien deports me to another planet, I will never see you again. What if the breasts on Mammary have a poor fashion sense and wear stretched out bras? I won’t be able to live there. Where will I be taken?”

“I don’t know what Lactavia plans for you,” Sondra said. “She might put you in a freezing cold cage and cover you with a foil blanket.”

“Foil blankets are not in style. Daddy, save me. I don’t want to be put in a cage without you.”

“I am not going to cage you,” said Lactavia. “Two fascist wrongs do not make a right. When Trump goes low, Mammarians go high. I am merely going to force you to live in the housing your husband rents to poor people. You will stay there until all the immigrant children are reunited with their parents.” As soon as Lactavia finished speaking, Ivanka disappeared.

“Where’s my daughter?” shrieked Trump.

“She’s residing in a Kushner rental property.”

“Which one?”

“I am not telling. The better for you to feel the pain you inflict upon the immigrants.”

“OK, well, I don’t care. I have another daughter. Tiffany is hot, too. I’ll just have to start paying more attention to Tiffany.”

But Ivanka was already phoning Tiffany to tell her that the Kushner rental property was tantamount to hell.

Unwilling to suffer the same fate and not at all like her half-sister, Tiffany actually proved to be effective. She saved the day by convincing Trump to reunite the immigrant children with their parents.

Lactavia released Ivanka, who kissed the ground when she crossed the threshold of her mansion, and the Mammarian and Sondra returned to the co-op.

“I never had a chance to drink my coffee. Would you like some?” asked Sondra.

“No. Coffee is not healthy for breasts. It was nice to meet you. I’ll be returning to Mammary. By the way, your milk container will always be full. You’ve got milk forever.”

Sondra raised a glass of skimmed milk to toast the real fact that Lactavia had turned Trump’s baby jails into one huge milk dud.

Marleen S. Barr is known for her pioneering work in feminist science fiction and she teaches English at the City University of New York. She has won the Science Fiction Research Association Pilgrim Award for lifetime achievement in science fiction criticism. Barr is the author of Alien to Femininity: Speculative Fiction and Feminist Theory, Lost in Space: Probing Feminist Science Fiction and Beyond, Feminist Fabulation: Space/Postmodern Fiction, and Genre Fission: A New Discourse Practice for Cultural Studies. She has a piece in the anthology, Alternative Truths, ( B Cubed Press, 2017), and she has edited many anthologies and co-edited the science fiction issue of PMLA. She is the author of the novels Oy Pioneer! and Oy Feminist Planets: A Fake Memoir.

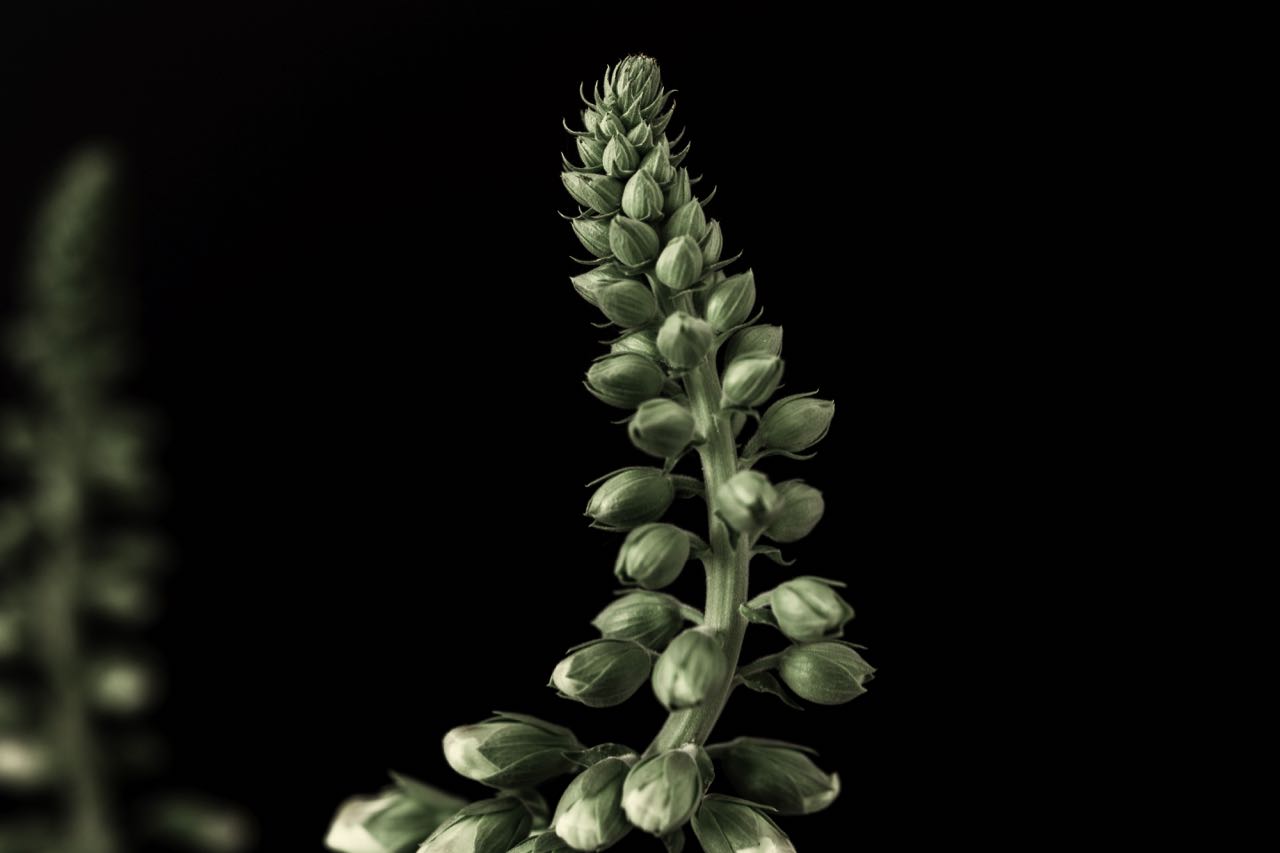

Photo by Mae Mu on Unsplash.